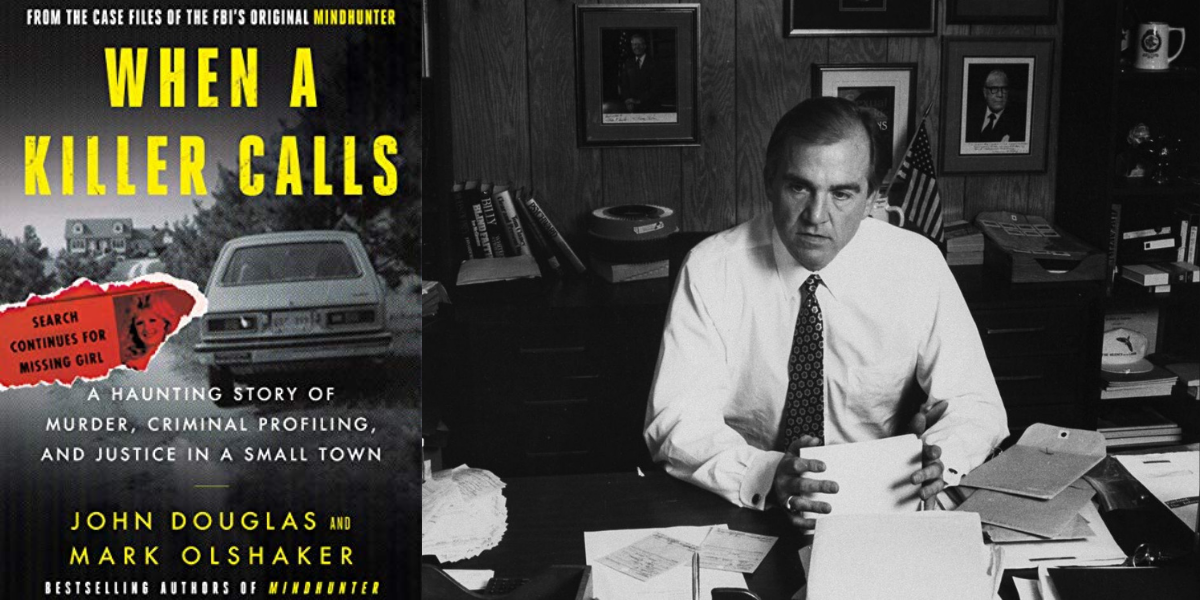

Read the Excerpt: When a Killer Calls by John Douglas

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

It had already been a busy day for Shari Smith. After rushing through breakfast and her parents’ mandatory short devotional and prayer session for her and her fifteen-year-old brother, Robert, she’d raced to school for practice for Lexing- ton High’s Class of 1985 graduation at the University of South Carolina’s Carolina Coliseum on Sunday. She and Andy Aun had been selected to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” so they had to rehearse with Mrs. Bullock, the chorus teacher. Once she got out of school, the rest of the day would be an unending sprint from one activity to the next, much, but not all of it, in preparation for the senior class trip—a cruise to the Bahamas the following week.

Shari loved to sing, and at Lexington High she’d been the jazz band soloist, a chorus member, and a singer and dancer in the stage choir. She’d made All State Chorus Honors her sophomore and junior years and participated in the Governor’s School for the Arts as a senior. That was all in addition to three years of student council. She had auditioned for a singing and dancing job for the summer at Carowinds amusement park up on the state line with North Carolina, southwest of Charlotte, where her older and look-alike sister, Dawn, was already per- forming. Despite the fact that they seldom took high school students, Shari had won a place, and she had looked forward to spending the summer performing with Dawn, who was living in Charlotte in an apartment with two roommates for the summer, and like Dawn, to majoring in voice and piano at Columbia College in Columbia, South Carolina. The two stunning, blue-eyed blondes had regularly sung solos and duets at Lexington Baptist Church where the Smiths belonged, and the Smith Sisters, as they came to be called, had fulfilled numerous requests to sing at other churches in the area. Shari liked to practice her dancing on the paved basketball court in front of the garage when Robert wasn’t shooting hoops. Sometimes she would bring their mom and dad out to be her audience.

But Shari’s dreams for the summer had been dashed. She had spent several weekends at Carowinds learning her routines for the country show. After only a few rehearsals, she became hoarse and had trouble projecting. Her mom and dad had taken her to a throat specialist, who gave them the bad news: Shari had developed nodules on her vocal cords. She would need complete voice rest for two weeks and no singing after that for another six. Shari was heartbroken that she would not be able to work at Carowinds that summer. The only consolation was that she’d be joining Dawn at Columbia College in the fall.

At about ten o’clock that morning, Shari called her mom from school and said she would call again when she was leaving so they could meet up at the bank to get traveler’s checks for her trip. She called again around eleven o’clock, saying she was not yet ready but would call back soon. Their parents generally insisted she and Robert call in frequently to let them know where they were, but that was one of the rules she didn’t object to, because Shari liked to talk. For the yearbook’s Senior Superlatives, Shari had been voted Wittiest. She’d also been voted Most Talented, but you weren’t allowed two superlatives, so she’d relinquished that one to another girl, who was thrilled with the honor.

There was still so much to do to get ready.

About 11:30 a.m., Shari called home again and said her mom could meet her in half an hour at the South Carolina National Bank branch in the Lexington Town Square shopping center. Shari asked her to bring her a bathing suit and towel for the pool party she was going to at her friend Dana’s house a few miles away in Lake Murray after the bank. She could change out of her baggy white shorts and black-and-white-striped pullover top when she got to her house.

At the bank, Shari connected with her boyfriend, Richard Lawson, and her good friend Brenda Boozer. She was so happy to be surrounded by three people she felt so close to. After getting the traveler’s checks, Shari and Brenda headed over to the party with Richard, leaving their cars in the shopping center parking lot.

Shari called from Dana’s at about 2:30 that afternoon and said she was coming home, throwing a shirt and shorts on over her two-piece bathing suit before she and Brenda left with Richard. About fifteen minutes later the trio got back to the shopping center, where Brenda and Shari could each retrieve their cars. Brenda said goodbye, and Shari and Richard sat in his car for a little while by themselves. Then Shari got into her own little blue Chevy Chevette hatchback and took off for home, with Richard following her until she turned down High- way 1, heading toward Red Bank.

The Smiths lived out in the country, in a house they built on twenty acres of land on Platt Springs Road, about ten miles outside of Lexington. The house was set back from the road on a rise, up from the 750-foot-long driveway, so there was plenty of privacy. The girls weren’t thrilled about moving from their previous home on a cul-de-sac in the comfortable Irmo community in Columbia, where their friends were close by and their schools only a mile away, but their dad had been raised in the country, and he thought it would be the best way to raise his own children. At their new home, there was enough land to build a swimming pool and for Dawn and Shari to keep horses, though by the time Dawn left for college, Shari and Robert had become more interested in riding a small motorcycle around the property and the horses were sold. The two kids would ride, sometimes for hours at a time, playfully squabbling about who was getting more time on the bike. Despite her feminine, blond beauty and angelic singing voice, unlike Dawn—whom her younger sister used to tease as a “goody-goody”—Shari had a lot of tomboy in her.

Somewhere around 3:25, Shari pulled into the Smith driveway and stopped the Chevette to check for mail at the pole-mounted wooden mailbox, as she always did when she came home. Since it was only a few steps from the car, she kept the motor running and didn’t bother slipping on her black plastic jelly shoes.

It was Friday, May 31, 1985.

Bob and Hilda Smith had been lounging around the backyard pool when Shari called to say she was leaving Dana’s party. They came in shortly after that so Bob could get ready for the golf game he’d scheduled. Bob, an engineer who had worked for the highway department, now sold electronic scoreboards and signs for a company called Daktronics and often worked at home. He also volunteered to minister in prisons and boys’ correctional schools. Dawn and Shari often accompanied him to sing. Hilda was a part-time substitute public school teacher.

As she glanced out the window, she saw Shari’s blue Chevette parked at the beginning of the driveway. When the car hadn’t moved after a few minutes, Hilda concluded Shari must have received a letter from Dawn and stopped to read it. Shari loved hearing from Dawn, and Hilda was more than a little afraid that Shari was living vicariously through her big sister since her summer plans to sing and dance at Carowinds had been wrecked by the vocal cord problem. Hilda and Bob were devoutly religious people and had tried to bring up their three children with the same reverence and faith. Shari was so shattered by not being able to be with Dawn that summer and share the stage with her that Hilda sometimes questioned why God had delivered such a big disappointment to her younger daughter.

About five minutes later, when the front door had not opened with a bubbly Shari rushing in, Bob looked out the window of his home office and saw her car still parked down by the road. That was odd. Hilda told him Shari was probably still sitting in the car reading a letter from Dawn, but Bob thought something must be wrong. Shari had a rare medical condition called diabetes insipidus, also known as water diabetes, that causes persistent thirst and the frequent need for urination, so there is a near-constant danger of life-threatening dehydration. There was no cure, but Shari took medicine that replaced vasopressin, the hormone that regulates fluid balance that her body couldn’t produce. When she was little, she had to have a painful shot with a large needle every other day. Later, thankfully, a nasal spray was developed to replace the injections. One container was always in Shari’s purse, with another kept in the refrigerator at home. If, for some reason, Shari had not taken her medicine, she could pass out and eventually become comatose. Whatever the reason she hadn’t come down the driveway yet, Bob was worried.

He quickly grabbed his keys, went to the garage, got into his own car, and headed down the long dirt driveway.

A few seconds later he was at the road. The driver’s side door of Shari’s car was open, and the motor was running. There were letters on the ground near the open mailbox. But he didn’t see Shari. He called out to her but got no answer. He looked inside the open car door. The towel Hilda had brought Shari was on the driver’s seat, Shari’s handbag was on the passenger seat, and her shoes were on the floor. Bob pulled open the top of the handbag and rummaged inside. Her wallet and medicine were still there.

In the dirt, bare footprints led from the car to the mailbox, but—ominously—there were none leading back.

Order the Book

n May 31, 1985, two days before her high school graduation, Shari Smith was abducted from the driveway of her family home in South Carolina. Based on the crime scene and the abductor’s repeated and taunting calls to the family, law enforcement quickly realized they were dealing with a sophisticated and highly dangerous criminal. A letter arrived the next day entitled “Last Will & Testament,” in which Shari, knowing she was to be murdered, wrote bravely and achingly of her love for her parents, siblings, and boyfriend, saying that while they would miss her, she knew they would persevere through their faith. The abduction rocked her quiet town, triggering a massive manhunt and bringing in the FBI, which enlisted profiler John Douglas. A few days later, a phone call told the family where they could find Shari’s body.

Then nine-year-old Debra May Helmick was kidnapped from her yard, confirming the harsh realization that Smith’s murder was no random act. A serial killer was evolving, and the only way to stop him would be to use the study of criminal behavior to anticipate his next move before he could kill again. Douglas devised a risky and emotionally fraught strategy to use Shari’s lookalike older sister Dawn as bait to draw out the unknown subject. Dawn and her parents courageously agreed.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use