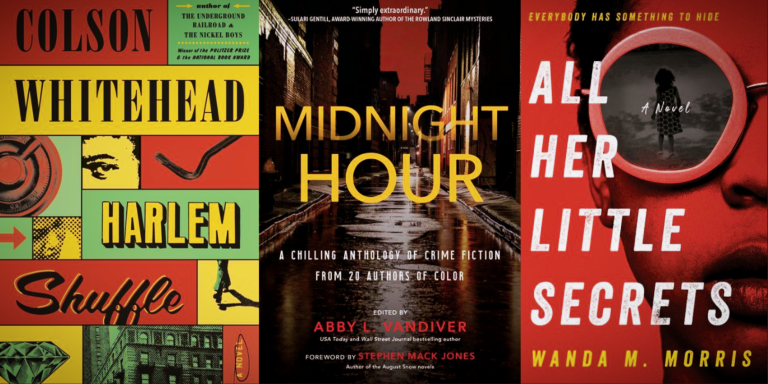

Read the Excerpt: We Lie Here by Rachel Howzell Hall

Thursday, June 25, 1998

Thursday, June 25, 1998

Every summer, the Afro-Americans came to hoot and holler at Lake Paz. Yes, every summer they arrived and talked loudly, and never kept private things private, and always spilled those secret things across the woods like cheap wine. And they always spilled those most-awful private things while good people, quiet people, tried to sleep.

Birdie glanced at the clock on her nightstand: almost an hour before midnight and those people in the cabin next door were doing this now. Of course they were. Their anger had slipped through the evergreens and rustled through the high grass to pull her from sleep.

They made the first Black family in these woods look flawless. Now, that family—the best of their people—would drive up, say hello as they moved from the car to their porch, bags of groceries already in hand and purchased from wherever they lived ten months out of the year.

The noise from that family would be laughter. A woman’s. A girl’s. His. Melodic. Harmonious. Pure. And he would play the piano, too. “Rhapsody in Blue” had been Birdie’s favorite, and he’d play a few other songs she recognized from the movies or television shows. The girl played piano, too. Not as good as her father, but it was still nice to listen to. Not that Birdie would ever admit that to Bud. Oh no, not ever.

Any time that family sat lakeside, Birdie would hear them speak soft words. I love you and You’re beautiful and Yes, I’d like another. And the way he looked at his woman and at his little one as he said those words . . . So soft. So dreamy.

What was that like? To hear soft words and silken declarations of love?

But that had been many summers ago. Tonight? Only hard words. Stop and Let me go and Please don’t, with the little girl crying, screaming, shrieking even.

Birdie studied Bud, still sleeping in bed beside her. He was snoring with his mouth open. Lost to this world for the next seven hours. That was for the best, since Bud didn’t much like the Blacks—not the ones who’d vacationed at that cabin summers before and definitely not the ones vacationing there now.

The girl shrieked again.

Birdie’s pulse jumped, and she pushed away the heavy quilt. Mosquitoes lunged at her bare, pale legs. She slapped them away, then grabbed the bedside can of DEET and sprayed. After pulling on her robe and pushing her feet into slippers, she tiptoed toward the doorway.

The hardwood floor creaked.

Bud snuffled, then turned over in bed. “Where you going?”

“Fresh air,” she said. “Can’t sleep.”

But he was already out again. Good. With Bud asleep, she wouldn’t have to involve Karlton, Lake Paz’s sole sheriff’s deputy. He’d warned Bud and Birdie several times: Leave them people alone, or I’ll have to bring you in again.

Let sleeping Buds lie.

Birdie grabbed the flashlight from the living room coffee table and the pistol from the empty sugar tub in the pantry. Just in case Bud was right.

The night air smelled of dying lake grass and still water and held the heat of the day. Croaking frogs and crickets vied to make the most noise. Tonight, the crickets were winning. Sometimes these were the only noises in the woods by the lake, and sometimes Birdie thought she was the only human surrounded by trees, water, and a sky as wide as forever.

Birdie now heard crying coming from the cabin. These people.

This lakeside community had one restaurant, a general store, two churches, and a bar. No crime. No problems. Maybe not as fancy as Lake Arrowhead with all those movie stars and tycoons building mansions around its shores. Lake Paz was natural, created by the San Andreas Fault. Or, according to legend, created by the devil himself. Lake Arrowhead couldn’t say that.

Beneath that moonless, forever sky, Birdie tromped through the crackling dry leaves and hard pine needles, past that gold Camaro (the only thing Bud actually liked about these people) with its god-awful thunderous muffler.

“Please, don’t! Ohmigod, stop! Please.”

All of this late-night hullabaloo made her underarms sticky with perspiration. What was he doing to her? And with their daughter right there? She’d heard that mental illness plagued the family. Every morning, she saw the woman, glassy-eyed and limp, wandering the shores of the lake. The child, wearing her Cookie Monster nightgown, trailing behind her mother, would stop to dip her hands into the water, but then call out Mommy, wait! because Mommy never stopped because she was drunk or whacked-out on drugs. The girl could’ve drowned a million times, and Mommy would’ve never known.

Maybe tonight he had tired of her spells, of searching for her again in the woods, of finding the little girl alone on the porch or playing by herself near the lake again.

Or maybe she cheated on him, and he found out and threatened to leave.

Or maybe he cheated on her, and the silly young thing had been enough of a fool to ask him about it.

“I’m begging you!”

Birdie’s blood chilled. Crazy or not, any woman—white, Black, purple—knew desperation when she heard it. She slowed in her step as she came upon the kelly-green A-frame cabin, the nicest cabin at Lake Paz. It had a basement, a hot tub, and a deck that overlooked the lake. They can’t do anything without flash and noise, Bud had complained, even though he’d wanted both a hot tub and a deck. Even though he owned the town’s only general store, he still couldn’t afford those fancy-pants things.

Hesitant, Birdie climbed the porch steps and pushed the doorbell.

As she waited, worry flitted around her belly like fireflies.

No answer.

She ran her fingers through her short blonde hair, then banged her fist against the door. “It’s Roberta Sumner from next door. I’m gonna call the sheriff’s if you don’t open up.” She slapped at her neck—she’d forgotten to DEET there, and the skeetos were eating her alive.

The door cracked open. A smell wafted through that small slit. It wasn’t alcohol. It wasn’t drugs. Not even blood. Did terror have a scent?

Birdie stuck her hand into the robe pocket hiding the pistol. All had quieted in the cabin. Even the girl had stopped crying.

The woman’s eye, bloodshot and swollen from crying, peeked out at her. “Mrs. Sumner, how are you?” Always polite, she now sounded hoarse, tired.

“You all are too loud.” These hard words made Birdie a little dizzy, a little nauseated. Because that wasn’t what she’d meant to say, not right away. A Nebraskan, she’d been raised to offer pleasantries first—how do you do, lovely evening isn’t it, that’s a lovely coat. It was almost midnight, though. “You’re gonna wake up the dead making all that noise.”

“I’m so sorry,” the young woman said.

Birdie tried to peer past her into the living room. The space was dark and quiet. Too dark. Too quiet. She gripped the pistol tighter. “Everything okay?” she asked. “Do you need the police? An ambulance?”

“I’m fine, thank you,” the woman said. “Just a little disagreement. Nothing serious.”

Birdie snorted. “More than a little disagreement, gal. And it sounds very serious. You woke me up, and you damn near woke Bud up, too, and you and me both know . . .”

The woman’s eye widened.

What they both knew burned in the small space between them. “We won’t trouble you again, Mrs. Sumner. I’m so sorry.”

Birdie squinted at the young mother on the other side of the door. She knew her entire face—tawny skin with freckles across the bridge of her nose, lips that usually curved into a smile but had broken tonight. Those brown eyes—or brown eye—weary, no longer merry. A flirt, she’d tried to soften Bud with those soft eyes and generous smile. The poor thing didn’t understand that Bud would never, not ever . . . not even with a pretty thing like her.

“We’ve cooled off, I promise,” the woman said. “We’re leaving tomorrow. This will be the last fight you’ll hear. I promise, absolutely promise you.”

Birdie said, “Good. You take care, okay? Get some help.” She leaned in closer and whispered, “You need anything, just leave me a note beneath my doormat. Nobody else has to know, okay? Just between us gals.” She winked.

The woman nodded and whispered, “Thank you, Mrs. Sumner.”

The front door gently closed, and Birdie started back to her own cabin. In the middle of her journey, she paused beneath the pine trees and cocked her head to hear . . .

Not a whimper. Not a word.

In the bathroom, Birdie grabbed the bottle of pink calamine lotion from the medicine cabinet and spread it across her neck, arms, and legs until she looked like a hot dog. Then she—

What was that? She closed her eyes to hear . . . Bud snoring.

Mosquitoes buzzing.

No, it sounded like a small . . . pop. Like a light bulb blowing out or . . .

Yes, she’d check under the doormat first thing tomorrow.

“Bird?” Bud shouted. “Come to bed. Can’t sleep with you making all that noise.”

“Coming, Bud.” She placed the cap back on the lotion. Yes, it sounded like a bulb blowing out.

A small . . . pop.

The city of Palmdale takes my breath away. A vise, it squeezes air from my chest and leaves me wheezing with weak legs and a racing heart. I may die there, and yet here I am, sixty-three miles north of Los Angeles, behind the wheel of my Jeep and driving closer to that place. I sip air in anticipation, practicing how to breathe through a straw so that I can live.

I must be crazy going back.

“Yara, explain it to me. I really want to understand. Why throw the party there, then?” Shane’s craggy voice booms over the Jeep’s speakers.

I glance at my boyfriend, just a face now on my cell phone.

His bourbon-brown eyes narrow as his lips lift into a smirk. A native Angeleno, he has no clue why anyone would want to live any- where other than LA, especially in the high-desert town where I lived for twenty-one of my twenty-four years.

“I’m hosting the party here cuz my family’s here and most of my parents’ friends are here. And since I’m paying for the whole thing, it’s cheaper to throw a party in Palmdale than a party in LA. Make sense?” Mom and Dad celebrated their twentieth wedding anniversary two days ago on May 15, and next Saturday night my sister, Dominique, and I will host the celebration they couldn’t afford back in 1999. In my mind, I see family friends watching as Dad gazes down at Mom, his eyes filled with love, and I see my parents dancing to Etta James’s “At Last,” feeding each other cake, and sipping a nice midrange champagne. I picture Mom later complaining about said midrange champagne and wishing, for once, that she’d sipped something decadent because if not now, then when? I see myself grinding my teeth but certainly understanding the desire to drink Moët. Later that night, I buy Mom a bottle of fancy champagne and then race back to Los Angeles as I ignore her Is something wrong? phone calls and eventually respond with Sorry I missed your call and I’m fine text messages.

So yeah. Instead of vacationing in Aruba, I’ve opted to spend nine nights and ten days in Palmdale planning this anniversary dinner party for seventy-five family members and friends at the Rancho Vista Golf Club.

Do I need a real vacation? Oh, hell yeah. But I also want to celebrate my parents’ love and show Mom and Dad that they matter to me.

“I understand all of that,” Shane says now, “but you also need a break, babe. To reset and see straight again.”

I grind my teeth. “I can see straight . . . and I did give you back your credit card.”

He says nothing, then: “Okay.”

“I can see it in my mind. You were talking to your sister, and I said—”

“Okay, Yara. I’ve already canceled the card. Bank’s sending me one overnight. And I wasn’t talking about you losing—”

“I didn’t lose—”

“I was talking about work and that . . . whole situation.” I grind my teeth again, this time to keep from crying.

It had been another long night toiling in the Tough Cookie writers’ room. The team had broken down a future episode on index cards that spanned the length of three walls. I’d fully participated in the brainstorming session for the episode that focused on Cookie’s grief over losing her only child to an asthma attack. Usually no one wants to hear the thoughts of a lower-level writer, but since I have chronic asthma, I knew firsthand the fear of not being able to breathe and the fear my parents experienced any time I wheezed. I’d finally been assigned to write the outline using the cards, which would be turned into the first draft of the script.

I don’t know how I did it but . . . I misplaced the cards. They weren’t in my bag. They weren’t in the Jeep.

My ass was grass, and after my showrunner ran out of awful shit to say to me, I cried in my car for half an hour and used my inhaler more than once just to catch my breath. Then I pulled pieces of me together, shambled back to the office, and promised my boss that I’d find the cards. Later that night, I found them on top of my refrigerator.

How did the cards get there? No idea. But that was then. This is now, and now, my hands clench the steering wheel. “It’s gonna be awesome. Everything’s gonna work out. Nothing will go wrong. It will be perfect.” My words taste like dust.

“You keep saying that, babe,” Shane cracks. “But I’m hearing you freak out.”

“It’s being in my parents’ house with all the cigarette smoke. That’s what you’re hearing.”

And he’s hearing low-key distress about future bickering with my mother and sister and having to listen to my parents’ arguments over the next week and . . .

“I don’t wanna go to Palmdale,” I shout-whine to Shane. “Don’t make me go!”

For the fifth time, my shaky hand ducks inside my satchel. And for the fifth time, I touch the inhaler’s plastic actuator, the vial of Ativan (just in case), the box of Benadryl, and the bottle of eye drops—my battle gear against the dust storms that swirl over the city this time of year, against the mentholated clouds of smoke that burst from my sister’s and mother’s mouths from dusk to dawn.

“You should’ve invited me,” Shane says now. “I would’ve made a great distraction from Gibson family madness. At least provided you some cover from the sniping.”

I bristle—I was waiting for him to say that.

He chuckles. “Your line is: ‘Oh, Shane. I should’ve invited you, too.’” “Ha. You’re the writer now?”

“I just figured . . . We’ve been together now . . . I just . . .”

I wanna grab the rose-gold cigarette case from the glove box. Mom gave me that case on my twenty-first birthday. The cigarettes inside are three months old, stale but never not smokable. No. I pluck the rubber band on my left wrist. The snap stings my skin, and beneath my wild curls, my scalp prickles.

I can stop smoking. I will stop smoking. I got this.

The desire passes. The wet-towel dread of going home has not. “You really gonna try to write up there?” Shane asks.

“As Yoda says, ‘Do or do not. There is no try.’ So I will do, hence my stay at Ye Olde Holiday Inn.” I pause, then add, “You’re such a skeptic.”

“I just know that sometimes . . .” “Uh-huh?”

“You get a little . . .” “Uh-huh?”

“Overwhelmed, especially when it comes to family stuff.”

There’s Palmdale in the distance. That’s Lake Palmdale to my right . . . Pelona Vista Park to my left. Storage facility . . . ARCO gas station . . . Del Taco . . . May not be Pink’s Hot Dogs, but Lee Esther’s makes a mean gumbo ya-ya and shrimp po’boy.

“I’m good,” I say. “I’m clear. I’m chill, and next week this time, I’ll have a complete treatment for Queen of Palmdale. Maybe even a bad draft of the pilot script.”

“Bet?”

“Bet,” I say, “and it’ll be grittier than my current engagement. I need to do this—Tough Cookie won’t last forever. Talk to you later?”

“Yep,” he says. “Promise me that you’ll call if you find yourself going into ‘that place.’”

“Promise,” I say, then end our call.

Not that I hate writing for Tough Cookie—it’s fun. After Moonlighting, it’s actually my mother’s favorite show, and not just because I’m one of its writers. A female private investigator named Cookie teams up with a washed-up action movie star to solve cases around the City of Angels. The title’s a little . . . eh, but she survived years on the LAPD, faced the loss of a child, and continued to work in a traditionally male field. So yeah. She’s tough. And her government name is Cookie. Therefore . . .

Writing for television pays well enough that I can afford to spend almost five grand for the party while helping my parents with my sister’s college tuition.

The new drama I’m writing is inspired by my life growing up in this city. Palmdale living is different from Los Angeles living.

With its hot, dry desert summers and cold, windy winters, Palmdale (and its fast-food chains, meth farms, and GameStops) scars the Mojave Desert. With the Nazi Low Riders, Peckerwoods, Lancas 13, and Black Menace Mafia, there are way too many bored little boys living out here in the middle of nowhere. And there are way too many exhausted girls who clench into balls to take the hits or push out another baby, to become too small to see. Add dust storms and firestorms and heat waves . . .

There’s no place like home.

My first sneeze comes the moment I open the Jeep’s door in the Holiday Inn’s parking lot. Grit swirls around the car. Not the cool-looking sci-fi grit in Blade Runner or Dune. It’s the ugly grit that scratches eyes and clogs noses. By the time I reach the check-in desk, my lungs have tightened and my contact lenses have torn my corneas. My pink bra strap slips off my shoulder as I paw around my bag for the inhaler.

The redheaded clerk’s name tag says Haylee. “Welcome. Last name?”

I’m still searching for the inhaler. It was just in here—I checked for it five times. I know that the inhaler is in the bag. Despite wearing faded blue jeans and a Tough Cookie crew tank top, I feel naked in the eyes of Haylee the hotel clerk.

And now two guests have appeared behind me with frowning red faces. The man shifts from foot to foot, and the woman pecks her blue eyes at my bare brown shoulders.

“I’m sorry, I’m . . .” I step out of line and roll my suitcases over to the seating area. I dump everything out of my smaller bag onto the coffee table. Pens, contact lens case and saline solution . . . prescription eyeglasses, sunglasses, lipsticks, three pairs of tangled earbuds . . .

No inhaler.

I cough and choke on my spit. My bra strap slips off my shoulder, and I wanna shove it in the lobby’s water feature.

Over at the desk, more people check in. Over at the bar, guests sip cocktails. Everyone is hugging, slapping backs, and kissing cheeks.

And then there’s me.

Back to the parking lot I go, my lungs tightening even more since I’m tromping through the swirling grit and kicking up more dust with the wheels of my suitcases.

The inhaler isn’t on the driver’s seat or on the passenger’s.

Stop. Breathe. Relax. I close my eyes and hold a breath . . . release . . . in . . . out . . . Okay.

The gold lightning bolt pendant around my neck dangles and circles like a dowsing rod, directing me to thrust my hand between the seats and center console and . . . There!

Shane’s missing Visa card. My face burns and I say, “Crap,” before shoving my hand back down between the . . . There! The plastic casing of the albuterol canister.

I take a picture of the credit card and send it to Shane.

I’m so freaking sorry!

I don’t know how it got in my car!

He texts back, No problem.

But it is a problem because by now, I’ve lost his headphones, the key to his gun case, and his car’s registration. Most times, too many times, I’m rundown from workdays that start at nine in the morning and end at four in the morning.

Gotta do better. Gotta be more mindful. Gotta check a sixth time, because five times obviously isn’t enough.

I shake my inhaler and then take a puff. Strands of my hair pull and straighten as the drug penetrates and opens my lungs. Glory be, I can breathe again!

In less than fifteen minutes, my hometown has already tried to do me in.

Room 303 is . . . fine. There’s a coffee maker and a fifty-inch flat-screen television. There’s a desk by a window that looks out to the parking lot and swimming pool. The clean room smells like lavender, and the tan carpet looks new.

I glance out the window, past the parking lot and to the foothills that ring the city. The ground is dusted orange with California poppies. At sunset, the hills will turn blue before plunging into the darkest black, and the skies will come alive as shooting stars streak across that vast nothingness. That’s when I think of moving back home. That’s when I miss watching Moonlighting DVDs with Mom and going shopping with Dominique a few times a week. That’s when I miss hiking the foothills with Dad to stargaze just like we did back when I was a kid.

But then I remember.

The dust storms.

The wildfires.

The white supremacists. The meth, so much meth.

And Barbara Gibson, my mother.

After graduating from USC, I left this place for good. Couldn’t stand the high temperatures, the commute time, the Confederate flags hanging over garage doors. Mom was pissed that I’d escaped her queendom, and she wouldn’t talk to me for a month. Usually, I celebrated these silences. This time, though, I thought we’d finally agree on something for a change—that she would be just as happy as I was that I’d left Palmdale. I was wrong. Once I landed my first gig as a writer’s assistant and deposited cash into her checking account, the sting of me defecting to Los Angeles diminished . . . but not completely.

My cell phone buzzes in my hand. A text message from Unknown.

Is this Yara?

Who wants to know? I text back.

Strangers have pitched me—I got a show idea. That’s when I immediately text back, Not interested. Then I block that number because I don’t wanna end up in court, accused of stealing some hack’s story idea about a chimpanzee who solves crime on Saturn. True story.

I have information that will change your life! Unknown texts.

Wrong number, I text back.

As I swipe to check email, another message from Unknown pops onto my screen.

Who do you think you are?

About the Author

Rachel Howzell Hall is the critically acclaimed author and Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist for And Now She’s Gone. A New York Times bestselling author of The Good Sister with James Patterson, Rachel is an Anthony, International Thriller Writers and Left Award nominee and the author of They All Fall Down, Land of Shadows, Skies of Ash, Trail of Echoes and City of Saviors in the Detective Elouise Norton series. She is a past member of the board of directors for Mystery Writers of America and has been a featured writer on NPR’s acclaimed Crime in the City series and the National Endowment for the Arts weekly podcast; she has also served as a mentor in Pitch Wars and the Association of Writers Programs. Rachel lives in Los Angeles with her husband and daughter. For more information, visit www.rachelhowzell.com

Amazon | Books-A-Million | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use