When People Go Missing in the Wildlands

Chapter 1

THE OLYMPIC PENINSULA

Jacob answered, “My life of wandering has lasted a hundred and thirty years. Those years have been few and difficult, unlike the long years of my ancestors in their wanderings.”

—Genesis 47:9–11

Much depends on a red bicycle. The bike is heavy and too small for Jacob’s athletic five-foot, eleven-inch frame. Ideally for a journey of this scale he’d ride a large, but the medium is what he has to roll with. After all, he figures, bikes are like surfboards—you don’t always have the perfect one for every condition. The important thing is the wave, the ride. And this one was free. The red Specialized Hardrock says Milwaukee Tools on it because his dad, Randy Gray, age sixty-three, won it in a raffle. Jacob—like his house-builder father, handy with a Skilsaw—fashioned a plywood rack behind the seat and bolted two milk crates to it side-by-side.

Instead of cycling-specific shoes with stiff soles and ski-binding-like clipped-in pedals favored by seasoned touring cyclists to allow for more power transfer to the cranks, Jacob’s bike is outfitted with stock flat BMX-style rattrap pedals that accommodate his running shoes and hiking boots. Not built for speed, not lithe, not pretty, a size too small, but hell-for-stout, as the builders say. And as utilitarian as a pickup truck. He’d recently sold his Volkswagen sedan and now the bike is his transportation, which suits him just fine.

Jacob’s preferred gear shop is the Port Townsend, Washington, Goodwill. He loaded his third-hand yellow-and-red Burley child trailer with pots and pans that still have the thrift-store price tags on them. His grandfather’s wool Hudson’s Bay blanket is heavy but warm, even when wet. A full roll of duct tape, a toolbox, camp stove, deck of cards, a Holman Bible, a tent, fuel bottles, a case of vintage Mountain House dehydrated meals, two first-aid kits, carabiners, climbing crampons, a bow and a quiver of arrows, a rain poncho, a sleeping bag, spin-cast fishing rod and reel, and enough tarps, rope, and bungee cords for a one-ring circus. The bike, trailer, and supplies weigh as much as the 145-pound twenty-two-year-old does soaking wet. Which he is.

The weather is snotty, which it never isn’t in northwestern Washington in early April, but that doesn’t slow him down. Jacob, a keen surfer who grew up on the beach in Santa Cruz, California, is ionized by water, as Randy puts it—whether surfing on it or riding in it. His dad talks of getting a dose of negative ions via whitewater, no matter how cold. Jacob is known to frequently trunk it—not don a wetsuit even when conditions warrant, which in the cold currents off Santa Cruz is most of the time. Jacob loves water, the colder the better.

What Randy’s ion theory lacks in scientific proof, it more than makes up for in shaka vibes. “Even if we don’t go surfing, we’ll get a mocha and go down to the beach and watch the sunrise,” Randy says. “That’s our thing, Jacob and me.” The two will sometimes sleep on the beach, with no sleeping bag, just watch the sunset and curl up in the sand like sea turtles until dawn.

Jacob has nowhere he has to be, and all the time in the world to pedal there. He doesn’t tell anyone where he’s going, not even Wyoma Clair, his grandmother, whom he’d been temporarily living with in Port Townsend. On April 4, 2017, he quietly leaves Wyoma fifty bucks on the table and heads out into the headwind and rain in the middle of the night.

When it hits social media that a cyclist is missing, there are reported sightings, few and mostly credible, but not very helpful. The cycle touring season hasn’t ramped up yet, as most cyclists wait for the weather to temper. Car and truck traffic is light on Highway 101 at night. So it’s logical that no more than a couple motorists report seeing a young man on an overloaded bike pulling a trailer westbound through the driving rain. A man claims to have seen Jacob twice on April fifth, in Indian Valley and along Lake Crescent. On Thursday, April sixth, a woman reports having seen a man towing “a red trailer” climbing Fairholm Hill at one o’clock in the morning.

No one gives it much thought. Touring cyclists are legion here soon, and Jacob is just the first robin of spring.

Later that morning, a local Port Angeles woman named Stacey passes Jacob as he churns up the Sol Duc Hot Springs Road, about two miles upriver from the 101. The park entrance shack is closed for the season, but the steel gate is open because the park itself is open, as is the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort. Coming down-mountain later that afternoon, Stacey notices the rig, laid down 6.3 miles upriver from the 101; she’s curious enough that she snaps a quick photo of the abandoned contraption, a flash of red-and-yellow aluminum and nylon against the lush universe of rainforest greens. It isn’t a good place to camp or stash a bike for long, highly visible there under a Sitka spruce tree, not ten yards from the road, twenty yards from the river.

On the afternoon of April 6, an Olympic National Park worker radios his dispatch. “Dispatch, 7-4-1 Ron on North Plain. I’ve got a bicycle that has went off the Sol Duc Road about, ah, mile marker 7, and I can’t find anyone around it. You might want to send a ranger up here so we can see what’s going on.”

ONP Dispatch: “Copy, thanks for the info, 16:30.”

Dispatch connects him to Ranger John Bowie.

Ranger: “Ron, I’ll head that way. Is that bicycle down the bank a ways, or is it easy to get to?”

“It’s easy to get to. It’s got a little carrier on the back of it too. It looks like it crashed off the road.”

“Okay, so it didn’t look like maybe somebody hid it there to go off for a hike?”

“It doesn’t look like anybody’s hit it, he just went off the road. I’m gonna stay here until you get up this way.”

Ranger: “Okay.”

Employee sign-out.

Standing next to the bike, which is just off the tarmac, Ranger Bowie can hear the roiling Sol Duc River even though he can’t see it. There is a recurve bow and some target arrows poking out of the trailer. He sees four arrows stuck in the ground between the road and the bike and trailer; the arrows seem stuck there deliberately, in a row. A little strange, but he’s seen it all, probably meaningless. Bowie does a quick look-around and doesn’t find the cyclist. At six p.m. he calls Ranger Brian Wray and asks him to check it out in the morning.

On Friday, April 7, just before nine a.m., Ranger Wray arrives at the bike. No cyclist. No anyone. The four arrows are still there, stuck in the ground. No sounds but the rush of the Sol Duc River and spring birds—you could lie in the middle of the road and it’s more likely you’d die of cold exposure before getting run over by a car.

Rangers perform what’s called a “hasty search.” Some search-and-rescue personnel hate the term hasty search, preferring to call it the Reflex Phase of a search. “Hasty” implies half-assed, a lazy afterthought. At any rate, rangers don’t find anything other than the bike, trailer, and gear; they don’t know anything more than anyone else about where the cyclist could be. This is becoming a head-scratcher even to trained rangers.

Searchers use the acronym POS and sometimes joke that it stands for “piece of shit.” It stands for probability of success, finding the missing. At this point the POS still remains high—the bike’s owner will come walking out of the bush and greet them with a hello.

But what nags at the rangers is the positioning of the bike, trailer, and gear. Nothing is locked up or secured. There seems to have been no attempt to hide anything from the infrequent motorists. Rangers don’t think there’s much they can do other than kick through the ferns for evidence of any sort, and walk the riverbanks, looking for something washed up on the bank or snagged on one of several logjams. Still, is anyone even missing, just because they aren’t, at the moment, logically, where they should be?

Searchers speak of “scenario”—why and how did the target come to be missing? It appears that Jacob—or someone—has been organizing gear. A tarp is partially spread out. But no logic points them in any one direction.

The four arrows are puzzling to the rangers. A bow and practice arrows are quite the tools to pack on a bicycle outfitted for a multi-day tour. They ponder the significance of the number, four—the four arrows stuck in the ground in a line, when the remainder stay in the quiver, next to his recurve bow and fishing rod, are a head-scratcher.

Wray photographs the scene. It’s time to more closely inspect the cyclist’s belongings. Wray secures the bow and arrows in his duty SUV. At approximately 9:20 a.m. he calls the district ranger, Michael Siler, to get one of his bosses up to speed. The ranger looks through the other gear in the trailer. It’s surprising he doesn’t find a kitchen sink.

Wray finds some iodine tablets—good for emergency water purification—but figures this cyclist would have a water filter and bottles, which are not there. Logic points him toward the river, twenty yards or so away. It makes sense that the cyclist bushwhacked to the river for water. He—it’s assumed the cyclist is a he—slips on a rock and ends up in the cold, swift current. He can’t swim, or he hit his head and is unconscious, drowns. Or the current is such he can’t get out and succumbs to hypothermia in the thirty-something-degree water.

Or, he hitched a ride up to the lodge where he could soak his damp bones for an hour before catching a ride back to his bike.

Mountain lions live in the park, but an attack on a human would leave messy evidence. Same with a black bear, though a bear attack on a human is extremely rare here. More probable is an abduction, but that doesn’t make the top of any lists.

Park rangers see the full spectrum of human behavior—it’s possible the rider decided bike touring is not for him or met someone interesting and caught a lift to Seattle.

Though it’s more probable than human abduction, it’s less likely that the owner abandoned the bike to go on a trail hike—there isn’t a trailhead in the immediate vicinity, he didn’t secure his gear, and a hiker won’t get very far before hitting snow.

The bike, trailer, and gear along the Sol Duc Road is now what searchers call the “LKP”—Last Known Position. Rangers do not find a phone among the gear, but do find a paper list of phone numbers—they’re on to whose stuff this is. And they know where he was; now where the hell is Jacob Randall Gray?

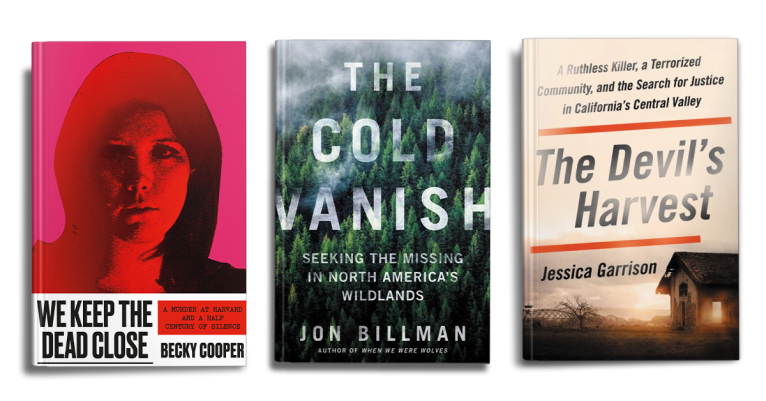

For readers of Jon Krakauer and Douglas Preston, the critically acclaimed author and journalist Jon Billman's fascinating, in-depth look at people who vanish in the wilderness without a trace and those eccentric, determined characters who try to find them.

These are the stories that defy conventional logic. The proverbial vanished without a trace incidences, which happen a lot more (and a lot closer to your backyard) than almost anyone thinks. These are the missing whose situations are the hardest on loved ones left behind. The cases that are an embarrassment for park superintendents, rangers and law enforcement charged with Search & Rescue. The ones that baffle the volunteers who comb the mountains, woods and badlands. The stories that should give you pause every time you venture outdoors.

Q&A WITH JON BILLMAN

Q: You cover dozens of cases in this book, both in quick mentions and chapter-long studies, but you must have encountered countless other missing person stories during your research. How did you decide what made the cut? Were there any you wish you could have included that didn’t make it?

A: I was much more drawn toward the cases that were not clearly criminal. The strangest, least-likely ones made the cut. Jacob’s case was foremost because it appeared that this smart, strong, outdoor athlete had just been raptured from his bike. Terrence Woods seemed to run frantically away—or toward—something unseen by witnesses. Michael Linklater may be dead somewhere in the Ontario bush, or he may still be tricking his family by leaving snowshoe tracks and pinching cans of food. There are cases that happen all the time that I’m sorry I couldn’t include, like David O’Sullivan, a twenty-five-year-old from County Cork, Ireland, who vanished on the Pacific Crest Trail just north of San Diego in April 2017. He’d reportedly taken on the trail name “Leprechaun” and there have been reported sightings, but none that have panned out. He wasn’t an experienced hiker, and his journey north had just started. Now his family back in Ireland has to get reports in the form of the leprechaun out in the desert that probably aren’t accurate, but for families like the O’Sullivans, tiny drops of hope are better than silence, I think, until more definitive news about David breaks. Bigfoot, portals, UFOs, now leprechauns.

Q: You mention a few possible changes to the current search and rescue system that might make it more efficient, such as having a missing persons database. Are there any other adjustments you’d like to see made to how S&R functions?

A: I’d like to see search and rescue incorporated into existing official organizations. In France the postal carriers are charged with checking on the elderly as part of their job. I’d like to see, say, federal and state wildland fire crews be on-call to deploy to missing persons searches. When I worked fire crew there was a lot of downtime, a lot of repainting buildings and cutting weeds—what more important job is there than finding a missing person? And as far as budgets go, there are few industries that burn money like wildland firefighting—they’d hardly notice the cost of a search.

The databases would certainly help, particularly in the colder cases. When you go to Grand Canyon National Park’s website, people missing in the park should be the first thing you see—scroll away from it if you’re not interested. There are a lot of people currently missing in that park. Hikers aiming for Longs Peak in the Rocky Mountain National Park Wilderness might think twice about gambling with the weather forecast if they were reminded how many hikers go missing up there. The lower-ranking rangers in Mesa Verde didn’t even know Dale Stehling is still missing in their park—if visitors found a random shoe or pair of glasses or a cap and they were aware Dale is still out there, maybe a connection could be made. Is it likely, no. But then so much in the world of missing persons is unlikely.

Q: In many of the cases you describe, it’s surprising that a person went missing—the trail was simple, or they were expert outdoorsmen, or were surrounded by other people. Yet hiking, mountain biking, and trail running remain popular activities across the U.S. Given how treacherous the wilderness is, what advice would you give to those of us who still venture out?

A: Leave breadcrumbs, even when it seems like overkill. It should be a reflex to text someone where you’re headed, even if it’s a two-mile snowshoe on a familiar trail. And I’m a big proponent of the windshield note. Analog. Often authorities find a vehicle at a trailhead, but still can’t be sure the missing person is on the respective trail. And now I carry two rolls of surveyor’s tape in my pack—when I’m in thick, unfamiliar territory I leave ribbon blazes (ties around trees) and untie them on my way out. That used to seem silly to me, but not anymore.

Last year I was cross-country skiing in familiar maple woods with my two dogs. I was out of water and decided to take a shortcut off-trail. The sun was going down and it was cloudy and I thought I had my bearings. Of course, I was too stubborn to follow my tracks back out and essentially made a giant corkscrew which took us through a big cedar swamp. I kept snagging my skis in downfall and the dogs had to porpoise through snow over their heads for an extra hour. I eventually would have hit a road, but it was a good reminder that you can still get lost in your backyard.

Q: You were clearly deeply enmeshed in the search for Jacob. What was it like to be involved during such a painful time for his family? Was it difficult to then depict yourself on the page, encroaching in some way?

A: I felt like an intruder at times. A voyeur. An ambulance chaser. But Randy, Mallory, and Micah—Laura too—welcomed me in. That’s a hard thing about the book coming out—I don’t want to violate their trust, misrepresent them. That’s one of the many things that keeps me up at three a.m. But without the book I wouldn’t have met the Gray family. They’ve taught me about heart and courage. Randy has taught me volumes about what it means to be a father and a friend and a human being.

How does a writer just seamlessly insert himself into a family crisis? I don’t think that’s possible. But Randy is a rara avis, he truly never met a stranger. You’re here, you’re gonna be part of finding Jacob. And that was it, the next thing I know I’m trying to keep up with Randy in the forest. Randy never introduced me to people as a writer. “This is my friend Jon from Michigan,” he’d say. “He’s helping me look for Jacob.” I was much more comfortable in that role than the guy writing about Jacob going missing. That’s Randy, the coffee cup is always half full, sunshine, and high tides.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use