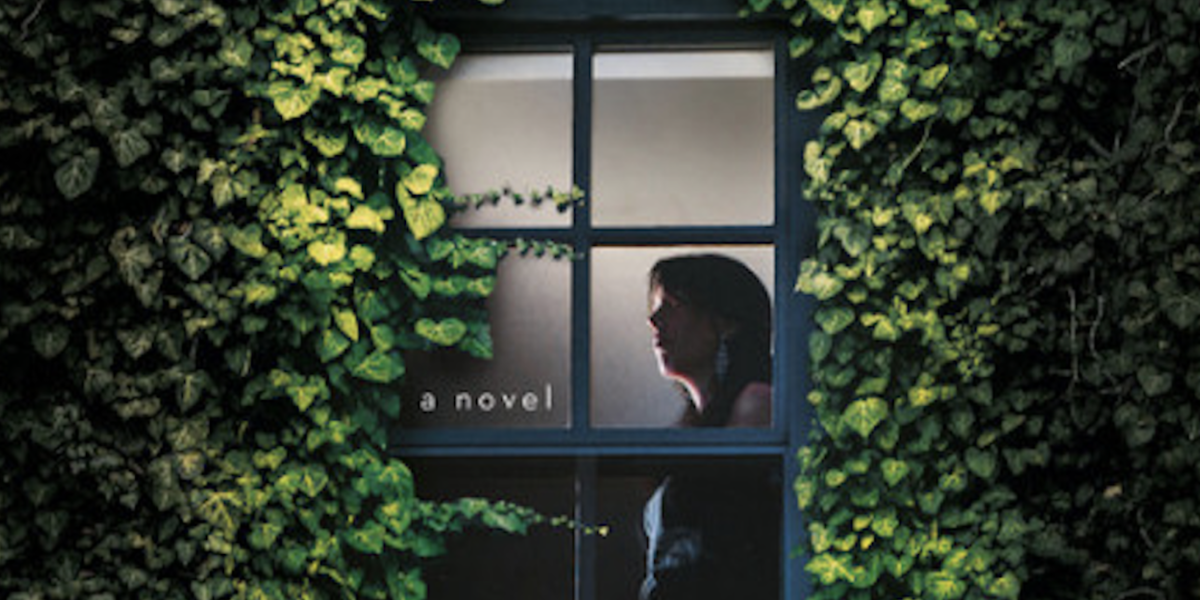

Read The Excerpt: The Lies You Told by Harriet Tyce

From the acclaimed author of Blood Orange, a dark new psychological thriller about the perfect mother, the perfect wife, the perfect family — and the perfect murder.

The Lies You Told by Harriet Tyce

Excerpt

1

It’s the first time I’ve ever slept in my mother’s room. That I can remember, anyway. It’s cold. My arm is the only part of me out from under the covers and my skin feels clammy, my fingers chilled. I roll over, tucking myself in fully, leeching off Robin’s warmth. She’s snoring gently next to me. It’s a couple of years since she’s wanted to sleep in with me, but the temperature of the house defeated her. The first night we arrived, she walked into the room I made up for her and walked straight out again.

“It’s freezing,” she said, “and I don’t like that weird painting on the wall.”

“I’ll move it,” I said. But I didn’t argue when Robin wanted to share my bed. I don’t want to let her out of my sight.

The duvet is too thin. I piled our coats on top last night for extra warmth, but they slipped onto the floor while we slept. I reach over and pull them back on, trying not to disturb Robin, eking out her sleep for at least a few minutes more. It’ll be cold when we get up.

The gas heater is still here. I remember sometimes in winter, the coldest days, that my mother let me dress beside it, warn- ing me not to get too close. I was never allowed to touch it then. I’m scared to touch it now. It’s brown, shiny, its corners sharp, gouges out of the paintwork. The ceramic burners are black with soot. I don’t even know if it’ll still work. The fireplace around it, once white, has yellowed, scorch marks above the fire. I looked away from the china ornaments on the mantelpiece last night, but in the dim light of the morning, I see they’re still the same; smiling shepherdesses, a Pierrot with a vacuous grin, all crowded close along the narrow shelf.

Robin shifts next to me, sighs, subsides back into sleep. I don’t want to wake her. Today is going to be hard enough for her. Anxiety spikes through me. The dank room lies heavy on me, thoughts haunting me of the warm house I’ve fled. The contrast between the spare room here, rejected by Robin, and her own bedroom that we’ve been forced to leave behind: the bed draped with pink hangings, the sheepskins on the floor. There are no sheepskins in my mother’s house—only a ram’s skull still displayed on the stairs, resplendent in his horns.

It’s safe, though. Far away. Robin rolls over in bed, closer to me, her arm warm beside mine, the little knitted meerkat my best friend Zora made for her held tight in her hand. My breathing eases. After what happened, I would always have felt chilled in that house, despite the warmth. I shiver now at the thought, the shock still raw. Deep breath in, out. We’re here now.

I reach over and pick up my phone from the bedside table— nothing. No messages. Its battery is nearly out—of course there aren’t sockets beside the bed. But the electricity is at least still working. As long as we don’t electrocute ourselves before I’ve had a chance to get the wiring checked. I lie back, listing all the jobs that are essential for the safety of the house, overwhelmed at the number of tasks ahead of me. At least there won’t be time to think about anything else.

“What time is it?” Robin mutters, turning over to stretch her limbs.

“Nearly seven,” I tell her. I pause. “We’d better get up.”

For a moment longer we lie there, both reluctant to brave the cold. I steel myself, pushing the covers back in one go and jumping to my feet.

“You’re so mean,” Robin says, sitting up fast. “Do I have to have a shower? The bathroom’s freezing.”

“No, it’s OK. I’ll try and get it sorted for later.”

She runs through to her room and I hear her thumping around as she gets ready. I throw on jeans and a sweater without giving my outfit any thought. It’s too cold for vanity.

“I don’t want to go,” Robin says, a piece of toast in her hand that she puts back on the plate, uneaten. She sighs. My heart sinks.

“I know.”

“I’m going to hate it,” she says, turning away and putting her hair up into a bun twisted on the top of her head.

“It might not be that bad.”

“Yes, it will,” she says, staring at me. There’s no arguing with her tone.

She’s about to walk through the gates of a new school in Year 6, new uniform—box-fresh, crisp and stiff—years after everyone else has formed their gangs and factions. The uniform she’s wearing doesn’t even fit properly, collar too big around her throat, skirt too long. Her face is pale against the bright red of the new school cardigan, the stark white of the new shirt, everything we bought in a rush yesterday from the uniform shop up Finchley Road I remember from my own childhood. My throat tightens, but I make myself smile.

“It’ll be OK,” I say, an edge of desperation in my voice. “You’ll make some lovely new friends.” I pick up a piece of toast, look at it, put it down. I’m not hungry either.

“Maybe,” Robin says, her voice full of doubt. She finishes dealing with her hair and pulls her phone out of her pocket, entranced immediately by the screen. I twitch, control myself. Is there a message from Andrew, wishing his daughter good luck at her new school? I don’t know if Robin and her dad have spoken since we left. . . since we had to leave. Robin keeps scrolling down, eyes flickering.

“Anything interesting?” I say in the end, unable to stop myself, trying to keep my tone light. “Has your dad messaged?” Casually, I pick up my own phone and put it in my bag.

Robin looks up, her face still and pale, eyes dark as her hair. She shakes her head. “Not Dad,” she says. “Haven’t you spoken to him?”

I smile, neutral. I need to move the conversation on. She has to believe this is all normal. She doesn’t need to know that the last contact between her dad and me was a hissed exchange on the phone before his number went dead. Just go, he’d said. I don’t want you here any more. Either of you. Loathing in his voice I’d never heard before.

I’ve been silent too long. She’s looking at me, a question starting to form on her face.

“Any gossip? You chatting to someone?” I say with an effort. Over the last couple of months, there’s been a complicated spat between Robin’s friends and people in her old class, and I’ve found the updates strangely compelling.

“Everyone’s still asleep, Mum. It’s the middle of the night back home.”

“Sorry, yes. Of course. I wasn’t thinking.” The words hang in the air, before Robin relents.

“But there’s a load of messages from last night while I was asleep. Tyler sat next to Addison on the bus on Friday instead of Emma and now no one is talking to Addison.”

“Oh, lord…”

“I know. It’s so stupid.” She looks at her phone once more before tossing it down.

“Maybe it’ll be easier being at an all-girls school,” I say, striving for a tone of conviction. Failing.

Robin shrugs. “I guess I’ll find out.”

The last year of primary school. Memories of it, deep in my bones. Everyone turning eleven, some looking like teenagers, some still childlike. At least Robin sits in the middle of this spectrum, neither very tall nor very short, nothing extreme in her development that stands out. It’ll be hard enough anyway. Suppressing a shudder, I remember the rejections, the spite. Whatever else I’m facing, at least I never have to go through fitting in to a new school again.

“I don’t know how they’re coping without you to mediate.” “I don’t think they are,” Robin says, her face serious. “They’re falling out way more without me there. I’ll never see

the messages in time.”

“I’m sure they’ll work it out. And you’ll see them soon. In the Christmas holidays, maybe.”

Robin is silent. It’s too much change to take in. Too much, too fast. My world and Robin’s turned upside down in a scurry of days. The air lies heavy.

“I know this is difficult,” I say. “But we can make it work. We were lucky that this place came up. Your school back home was great, but we’ve always wanted you to go to school here, in London. You’re going to love it.” My voice falls off. I remember that last rushed day in Brooklyn as I threw clothes into bags, a smile fixed to my face as I lied through my teeth to Robin about why we had to leave. Right then. No time for goodbyes.

“And you were happy there? You’re sure I’m going to like it?” Her face is pinched, suspicious.

“Yes,” I say. Another lie. But only a small one this time. “But you told me you didn’t have the best childhood,”

Robin says. She’s sharp, my daughter. Too much so.

I quickly gather myself. “That was more to do with home,” I say. “Your grandmother. She wasn’t very keen on kids— even her own. School was an escape. I mean, of course there were difficult bits, but I made some friends. I loved the library. They made me school captain in Year Six and put my name up on a board—that was pretty cool. It was definitely better than here.” I gesture around me at the tired, cold kitchen.

Robin smiles. “At least it’ll be warm,” she says, attempting a joke. I reach across the table to hug her and after a moment she hugs me back. “Let’s get out of here. You don’t want to be late. Not on your first day.”

Robin nods and crosses the room to pick up her bag and pull on a pair of gloves. I put on a wooly hat to hide the worst of my greasy hair, and we head out.

We walk to the bus stop, our footsteps slapping in time against the pavement. I glance over at my daughter. Her face is set, her chin firm, almost grown-up yet still so young.

I don’t know what lies ahead for us. I want to be calm. But I can’t shift the fear at the pit of my stomach, heavy as our steps on the ground.

2

I sit next to the bus window, leaning my forehead against the glass. The 46 bus is full, and slow, lumbering from stop to stop from Camden to St. John’s Wood. I remember the route so well I could walk it with my eyes closed. It’s all different, all the same, layers of new builds, slicks of fresh paint on top of the old buildings.

I glance at Robin’s profile—she’s still entranced by her phone. She snorts with laughter, lifts her head.

“Emma sent me a big update. So much drama. I’m glad I’m not there having to deal with it all,” Robin said, tucking her phone in her bag.

I almost believe her.

My stomach clenches as the familiar bus stop draws close. All of a sudden, I’m aware of the traffic noise around me. The screeching of brakes, horns sounding, a man yelling fuck off in the distance. Exhaust fumes leak in from the street, catch at my throat, a steady stream of black SUVs crowding past us. We’ll be the only ones turning up to school on the bus.

The bus brakes unexpectedly and my head bangs against the glass. I shut my eyes against the memories.

* * *

“We’ll never get a place,” I’d said when I was first told of what my mother had done, two years earlier. “It’s too late. It’s too competitive. There’s no way any spaces will come up now. Not at the beginning of Year Four, not in two years. There will be a waiting list as long as my arm. She thinks she can control everything, but she can’t. Even if we were going to go along with it, we wouldn’t be able to.”

And this had been true, my delight great when the admissions officer gave my reluctant inquiry short shrift.

But that was before it all went wrong. My marriage with Andrew, collapsing in two short years. It was a surprise, then, to receive a call only a couple of weeks ago from the same admissions officer telling me there was a space now available if Robin could start immediately. I was about to say no again, but something gave me pause. I’ll think about it for a bit if that’s OK. Those words emerged instead.

Nothing could have prepared me for the desperation with which I’d call her forty-eight hours later, heart in mouth, to ask her—beg her—if the place was still available. Please. Just a standard offer to her, a way to fill an unexpected gap in the class. A miracle for me—everything I’d needed for our escape. An escape I never knew till then I’d need. The condition of my mother’s controlling legacy met by sending Robin to Ashams—without her attendance, I wouldn’t have been allowed this house or the small income from my mother’s estate—just enough to live on now that I’ve left my marriage behind.

When I last left my mother’s house, over a decade ago, I swore on my life I’d never go back. Never let my mother control me again.

But I’d break any promise for Robin.

* * *

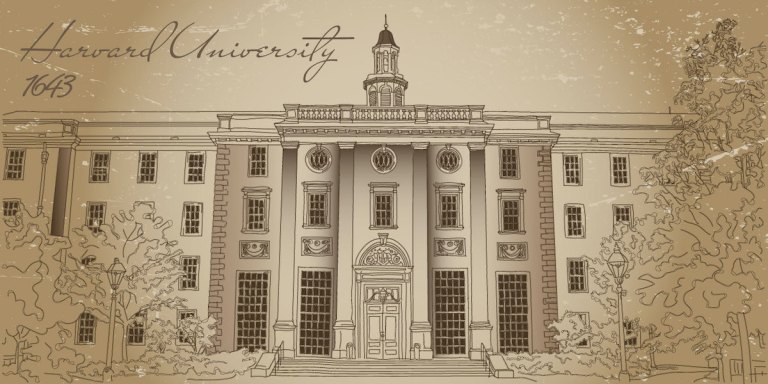

Now we’re at the school gates, and my hands are curled tight in my pockets. Even through the eyes of an adult, it still looks huge, imposing. Architecture fitting for the most prestigious girls’ school in north London. I try not to imagine how intimidating it must be for my daughter.

There are two sets of iron gates, a formal flower bed in between with box hedges and cyclamen. From each gate the drive curves up to a wide flight of stairs that leads to the front entrance. Despite the grandeur of its fittings, it’s not set back that far from the pavement—a carriage would have had to maneuver carefully around the gates rather than sweep majestically through. This place couldn’t be more different from Robin’s old school, a modern building on a quiet street. This school carries the weight of history, a gravity that seems to belie the presence of actual children behind those great doors.

I look down at Robin. Her face is tight, the color drained from her cheeks.

“It’ll be OK,” I say. I want to promise. I can’t.

Robin looks about, her gaze unblinking. She clutches my arm. “This is an elementary school?”

“It is. It’s a lot more friendly than it looks, I promise.” I stop myself from crossing my fingers.

“Wow.”

“We’d better go in,” I say, and she nods. We walk slowly across the drive and up the stone steps. The doors are wide, wooden, with brass fittings polished to a high shine. I reach to open the door, but it’s pushed back hard from the other side. A woman walks out briskly, bashing straight into me. I jump back, startled, only catching my balance by grabbing hold of Robin by the arm and nearly sending her flying, too. My ankle turns over, a sharp pain shooting up my leg.

“Watch where you’re going!” The woman’s scorn is sharp in her voice. “I could have fallen down the stairs.” She pushes past us and marches off, her perfectly blow-dried hair bouncing on her shoulders with each step. I look after her, heart still pounding from the encounter. Tall, blonde. Hostile.

“Are you OK?” Robin says at the same moment another woman starts tutting and shouldering past us.

My throat tightens as though I might cry. Or scream at them all to fuck off. I brush moisture from my eyes with brisk fingers.

“I’m fine.”

Once we’re safely inside, and I’ve introduced Robin to the registrar and filled in the emergency contact forms, I stand next to Robin in an expectant manner.

“You can go now, Mom,” Robin says, and the registrar laughs. “She’s safe with us, Mrs. Spence.”

“That’s my husband’s name,” I say. I can’t bring myself to say ex-husband with Robin standing beside me. “My name is Roper. Sadie Roper.”

“Of course, Ms. Roper,” she says. They keep looking at me, waiting for me to leave.

Robin nods. “Go on, Mom.”

I look at the registrar. “You don’t need me for anything else? A tour, or meeting the form teacher, or something?”

She shakes her head. “Not today. You will meet Robin’s form teacher in due course. We’ll send you details of the parents’ evening.” She turns to Robin. “I’ll take you to your classroom.”

She whisks my daughter away from me before I can even say goodbye.

3

I head back fast to the bus stop on the other side of the road, the pain subsiding in my ankle as I go. I need to make some progress on the house and then get to chambers to see if there’s any work available. The long years spent away from criminal practice yawn in front of me, but I refuse to let them put me off. I’ve braved worse in the last weeks. Far worse.

It shouldn’t be this way. Anger courses through me: at Andrew for being such a bastard; at the rejection, the rage that’s driven me clean across the Atlantic, straight back into the clutches of my mother and that wreck of a house. Thoughts of a tidy new-build apartment drift through my head. White walls and clean wooden floors, not the dark jumble of a neglected Victorian house, windows obscured by overgrown ivy. A toxic legacy.

The bus pulls up. No good thinking about this now. I’ll wash, scrub, clean; bleach it all out. I take out my phone, ready to text Zora, invite her for dinner. My finger hovers over the screen for a moment before I write the message.

Surprise! Long story, but Robin and I are back and stay- ing at the house. Dinner tomorrow? Lots to catch up on xx

Planning for the future, no looking back.

* * *

As soon as I’m home, I look at the boiler I was too tired to examine the night before, discovering to my surprise that it’s relatively new. After a few minutes, it’s up and running. Warmth, hot water—that’ll chase away the demons.

Heartened, I get to it, scouring and scrubbing every surface in sight, not stopping for a second to let any thoughts of the past enter in, shutting myself off from any recognition of creaking floorboards or cracked tiles, the mark on the wall where my mother threw a book at me, the nail sticking out of the floor where I ripped countless pairs of tights, always forgetting it was there. As the dust lifts, so does the gloom in the house, and cold sunlight poking through the dirty glass of the kitchen window lifts my mood a little more.

After a couple of hours of frenzied activity, the kitchen is usable. It’s still the same oven, the one I remember from all those years ago. I test it’s working, remembering almost instinctively how long to hold the knob down before the gas catches light.

The old electric kettle is still here, its cord frayed, the metal of the wire exposed. I remember telling her to throw it away the last time I was here, fifteen years ago. I pick it up and turn it in my hands for a moment, tracing the marks of limescale etched on its surface, before my chest tightens and a sour taste rises in my mouth. Why do you care if I get electrocuted? rings in my ears. I dump it in a black bin bag, a smile lifting the corners of my mouth. Digging through the cupboards, I take out a small saucepan and fill it with water, put it on to boil.

Even though the house is on a busy road, there’s no sound of traffic in the kitchen at the back. I’m unnerved by the silence. I look through the window of the back door onto the concrete patch outside. It’s overshadowed by evergreen trees—a yew, chill and dark in the corner, all the plants my mother used to tend brown and withered, dead leaves lying in drifts in the corners. I’ll cheer it up—geraniums, bulbs in big blue pots. I remember the time I brought a bunch of tulips home for Mother’s Day, handed them to her. So loud, she said as she thrust them from her, petals crushed in the sink. It’s bad enough being a mother, she said. I don’t need any reminders. I remember how small I felt at that moment, how stupid, my feet too big for me as I stumbled backward and fled from the kitchen.

Time to plant daffodils, snowdrops. Crocuses. Parrot tulips, the brighter the better. I’ll get Robin to help. Turning away from the door, I look again around the kitchen. It might be cleaner, but it’s still bleak, still empty.

The water boils and I make tea, sitting back down again, nursing the warmth of the mug in my hands. It’s nearly noon. Is it time yet for Robin’s lunch? Maybe the food will be better now. I hope it’s better now. I think about what we used to be served: lasagna swimming in grease, cold mashed potato, green-gray hardboiled eggs at the heart of a rock-hard veal and ham pie. I take in a deep breath, release it. Not now. I’m not going there. What lies beneath is worse, much worse, and I don’t have time. My thoughts snap back to Robin.

It’ll be OK, I’d said to Robin. Really welcoming. Reassuring phrases that rolled off my tongue. But in truth, it was never welcoming at all. Formal, assertive, utterly confident in itself. Sink or swim. That’s how it was all those years ago. Maybe it’s changed. I remember the grip of Robin’s fingers on my arm, clutching so hard I’m surprised they didn’t leave a mark. I hope it isn’t as bad as Robin feared.

I fear it might be a lot worse.

My tea cools rapidly, and I drink it in gulps, pushing the mug away from me when I’ve finished. I need to change to go into chambers and ask the clerks if there’s any work available for me. Realistically I know it might be tricky, but I can’t let doubt creep in.

Before I go, I want to sort Robin’s room out a bit more. It’s the room my mother used for guests, few though they were. I shovel out piles of old newspapers and torn magazines, ruthless in my clearing. A chest of drawers emerges, a wardrobe, old coats and jackets, a moth-eaten fox fur, its tail held in its mouth with a tortoiseshell clip. It all goes into bin bags. A message arrives from Zora. Yes please to dinner tomo. I want to hear ALL about wtf is going on. I can’t believe

you’re back tho can’t wait to see you xx

I feel my spirits lift, a small chink of light breaking through. It will be so good to see her. But it’s going to be a long explanation. I send back a thumbs up emoji, unable to muster any more words.

Order Now

When Sadie Roper moves back to London, she's determined to pick up the pieces of her shattered life. First, she needs to get her daughter settled into a new school-one of the most exclusive in the city. Next, she's going to get back the high-flying criminal barrister career she sacrificed for marriage ten years earlier. But nothing goes quite as planned. The school is not very welcoming newcomers, her daughter hasn't made any friends yet and the other mothers are as fiercely competitive as their children. Sadie immediately finds herself on the outside as she navigates the fraught politics of the school gate.

But the tide starts to turn as Sadie begins to work on a scandalous, high-profile case that's the perfect opportunity to prove herself again, even though a dangerous flirtation threatens to cloud her professional judgment. And when Liza, queen of the school moms, befriends Sadie, she draws her into the heart of the world from which she was previously excluded. Soon Sadie and her family start to thrive, but does this close new friendship prevent her from seeing the truth? Sadie may be keeping her friends close, but what she doesn't know is that her enemies are closer still...

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use