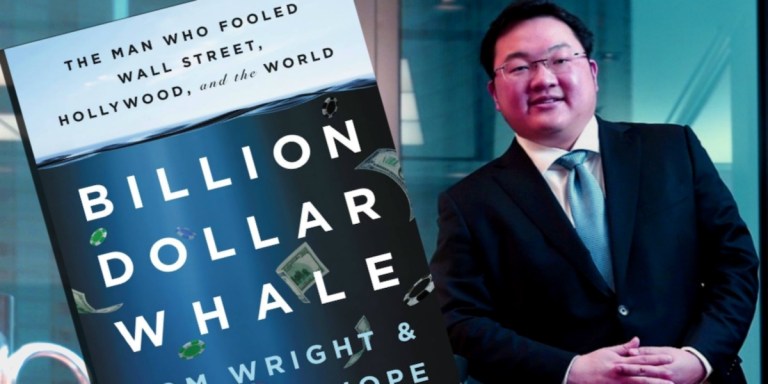

Read The Excerpt: Good Neighbors by Sarah Langan

From Believing What You See: Untangling the Maple Street Murders,

From Believing What You See: Untangling the Maple Street Murders,

by Ellis Haverick,

Hofstra University Press, © 2043

Fifteen years after the fact, our preoccupation with Maple Street seems quaint. The details aren’t especially gory. The number of casualties holds no candle to the Wall Street Blood Bath, or the Amazon Bombings in Seattle. What happened was horrific, but no worse than any calamity we now hear about five days a week. Why, then, is it a national obsession? Why do people dress like its key players on Halloween? The Broadway show, The Wildes vs. Maple Street, has run for more than a decade. During this immersive theater experience, the audience is asked to choose sides in a reenactment, arguing to the literal death* over who was at fault, and who was innocent. Every year, another media outlet reinvents the facts of what happened on that hot August day; the murderous fever that spread across an American neighborhood. Some blame the heat wave, the first of its kind. Some blame the sinkhole in the collapsed park nearby.

Still others blame suburbia itself.

My theory is this: Maple Street has stuck with us because no one has adequately resolved the mystery. It’s a nightmare in plain sight. We ask ourselves how an upstanding community could conspire toward the murder of an entire family, and we can make no sense of it.

But what if we’ve overlooked the most obvious explanation? What if the accusations lodged against the Wilde family were true? In other words, what if they had it coming?

* It’s role-play theater, the outcomes dependent upon how the game is played.

INDEX OF MAPLE STREET’S PERMANENT RESIDENTS AS OF JULY 4, 2027

100 The Gradys—Lenora (47), Mike (45), Kipp (11), Larry (10)

102 The Mullers—John (39), Hazel (36), Madeline (4), Emily (6 months)

104 The Singhs-Kaurs—Sai (47), Nikita (36), Pranav (16), Michelle (14),

Sam (13), Sarah (9), John (7)

106 The Pulleyns—Brenda (38), Dan (37), Wallace (8), Roger (6)

108 The Lombards—Hank (38), Lucille (38), Mary (2), Whitman (1)

110 The Hestias—Rich (51), Cat (48), Helen (17), Lainee (14)

112 The Gluskins—Evan (38), Anna (38), Natalie (6), Judd (4)

114 The Walshes—Sally (49), Margie (46), Charlie (13)

116 The Wildes—Arlo (39), Gertie (31), Julia (12), Larry (8)

118 The Schroeders—Fritz (62), Rhea (53), FJ (19), Shelly (13), Ella (9)

120 The Benchleys—Robert (78), Kate (74), Peter (39)

122 The Cheons—Christina (44), Michael (42), Madison (10)

124 The Harrisons—Timothy (46), Jane (45), Adam (16), Dave (14)

126 The Pontis—Steven (52), Jill (48), Marco (20), Richard (16)

128 The Ottomanellis—Dominick (44), Linda (44), Mark (12), Michael (12)

130 The Atlases—Bethany (37), Fred (30)

132 The Simpsons—Daniel (33), Ellis (33), Kaylee (2), Michelle (2),

Lauren (2)

134 The Caliers—Louis (49), Eva (42), Hugo (24), Anais (22)

TOTAL: 72 PEOPLE

116 Maple Street

Sunday, July 4

“Is it a party? Are we invited?” Larry Wilde asked.

They weren’t invited. Gertie Wilde knew this, but she didn’t want to admit it. So she watched the crowd out her window, counted all the people there. Gertie and her family had moved to 116 Maple Street about a year before. Is it a party? Are we invited?” Larry Wilde asked.

They’d bought the place, a fixer-upper, for cheap. They’d meant to renovate. To reshingle the roof and put in new gutters, tear up the deep-pile carpet and nail down bamboo. At the very least, they’d planned to seed grass across the patch-work lawn. But stuff happens. Or doesn’t happen.

The inside of 116 Maple Street was haphazard, too. As a kid, you might have visited this sort of home on a playdate and intuited the mess as happy, but also chaotic. You had a great time when you slept over. You never worried about the stuff you had to bother with at home: making your bed, hanging your wet towel, carrying your dishes to the sink. Still, you wanted to go home pretty soon after, because even with the laughter, all that mess started to make you nervous. You got the feeling that the management was in over its head.

Maple Street was a tight-knit, crescent-shaped block that bordered a six-acre park. The people there dressed for work in business casual. They drove practical cars to practical jobs. They were always in a rush, even if it was just to the grocery store or church. They didn’t seem to worry as much about their mortgages. If their parents were sick, or their marriages weren’t happy, they didn’t mention it. They channeled those unsettled feelings, like everything else, into their kids.

They talked about extracurriculars and sports; which teachers at the local, blue-ribbon public school were brilliant miracle workers, and which ones lacked training via the social-emotional connection. They were obsessed with college. Harvard, in particular.

The Wildes were different. With their finances out of sorts, Gertie and Arlo didn’t have the bandwidth to obsess over their kids, and even if they’d had the time and mental space, no one had ever taught them about creative learning and emotional intelligence, healthy discipline and consistent boundaries. They wouldn’t have known where to begin.

The kids, Julia and Larry, made fart sounds in public, and also farted in public. Julia was fast. Their first month on the block, she stole her dad’s cigarettes and taught the neighborhood Rat Pack how to French exhale. Larry was quirky. He didn’t make eye contact and had a flat affect. When he thought the other kids weren’t looking, he stuck his hands down his pants.

The Wildes knew that they’d been breaking tacit rules ever since arriving on Maple Street. But they didn’t know which rules. For instance, Arlo was a former rocker who smoked late-night Parliaments off his front porch. He didn’t know that in the suburbs, you only smoke in your backyard, especially if you have tattoos and no childhood friends to vouch for you. Otherwise, you look angry, puffing all alone and on display. You vibe violent.

Then there was Gertie. Before she met Arlo at the Atlantic City Convention Center, where he’d played lead guitar for the in-house band, she’d won thirty-two regional beauty pageants. Like a living Barbie doll, she still conducted herself with that same pageant training: phony smiles, over-bright eyes, stock answers to questions that begged for honesty. The neighbors who’d tried to befriend her had mostly given up, under the misapprehension that there wasn’t anybody home under all that blond. Worse, nobody’d ever told Gertie that mom cleavage isn’t cool. She didn’t know that when she wore her halter tops, painted gold chain-necklaces dangling between her breasts, she might as well have been waving a great banner to the other wives that read: insecure floozy who wants to steal your husband and make your kids ashamed you’re not a 5’10”, blond viking with perfect skin.

That summer of the sinkhole was the hottest on record. Because the center of Long Island was as concave as a red blood cell, there wasn’t any mitigating wind. Just mosquitoes and crickets and living, singing things. The smell was saltwater sifted through too-ripe begonias.

The Wilde family had just finished dinner (cheese toast washed down with fizzy water; Trader Joe’s frozen cherries for dessert). They’d heard the sounds of people, but hadn’t noticed anything special until the notes of a Nirvana song carried through their windows.

I’m not like them, but I can pretend.

“Is it a party? Are we invited?” eight-year-old Larry asked. He lifted Robot Boy from his lap. Nobody was allowed to call it a doll or he got embarrassed.

Gertie hoisted herself to the window and pulled back the thin curtains. She was twenty-four weeks pregnant, so everything she did took a few seconds extra, especially in this heat.

It was seven o’clock exactly, and everybody out there seemed to have gotten the same memo, because they were carrying quinoa salad in Tupper- ware, or chips and salsa, or a sixer of artisanal beer. Gertie quick-counted: the Caliers-Lombards-Simpsons-Gradys-Gluskins-Mullers-Cheons-Harrisons- Singhs–Kaurs-Pulleyns-Walshes-Hestias-Schroeders-Benchleys-Ottomanellis-Atlases-and-Pontis. Every house on Maple Street was accounted for, except for 116. The Wilde house.

“If it was a party, Rhea Schroeder would have told me,” Gertie muttered.

Twelve-year-old Julia Wilde lifted a single blond eyebrow. She wasn’t pretty like her mom, and had decided early to contrast this by being funny. “Loooooks like a party. Smellllls like a party . . . ”

Arlo poked his head next to Gertie’s and together they leaned. He was wearing just a Hanes T-shirt and cutoff Levi’s, his sleeve-inked arms exposed. On the left: Frankenstein’s Monster and Bride. On the right: the Wolf Man and the Mummy. Gertie was bad at reaching out. At asking. But he was a warm person who’d always intuited when she needed to be reassured. He kissed the top of her head.

“Fun,” he said. “Should we go?”

“I’m game for a second dinner,” she answered. “Guppy’s growing bones today, I think.”

“I don’t understand. How is this not a party?” Larry called from behind. “Sounnnnds like a party,” Julia said.

It was a party, Gertie finally admitted. So why hadn’t anybody posted about it on the Maple Street web group? Was Rhea Schroeder mad at her? It was true they’d fallen out of contact lately, but that was because Gertie was exhausted most nights. This third baby was heck on her body. And Rhea’s summer course load was full, plus she had those four kids. It had to be an accident that she hadn’t been invited! Rhea would never intentionally do her wrong.

She should have expected a Fourth of July party! She should have asked around. For all she knew, the neighbors had come up with the idea only this morning. There hadn’t been time to post about it. Besides, you don’t need a written invitation to a block party . . .

Do you?

Just then, Queen Bee Rhea Schroeder passed by their window. She was overdressed in a fancy Eileen Fisher linen pantsuit; white and stainless.

“Rhea!” Gertie called through the open window, her voice stage-loud, reverberating all through the street and into the giant park. “Hi, sweetie! How are you?” Then she waved. Big and pageant-winning.

Rhea looked straight into Gertie’s window—into Gertie’s eyes. The attachment between them felt wrong. Like a plug connected to a faulty socket, sparks flying. For just a moment, Gertie was terrified.

Rhea turned. “Dom? Steve? Did someone bring chicken or do I need to make a Whole Foods run?” Her voice faded as she walked deeper into the park.

“That was weird,” Arlo said.

“She’s spacey. Smart people are like that. She probably didn’t see me,” Gertie answered.

“Needs to get her eyes checked,” Arlo joked.

“She sucks chocolate balls. So does her whole family. They’re ball suckers,” Julia said.

Gertie turned, hands resting on her full belly like a shelf. “That’s terrible to say, Julia. We’re lucky that people like the Schroeders even talk to us. Rhea’s a college professor! You’re not giving little Shelly a hard time, are you? She’s too sensitive for that.”

“Sensitive? She’s a crazy bitch!” Julia cried.

“Don’t say that!” Gertie cried back. “The window’s open. They’ll hear!”

Julia hung her head, revealing strong shoulders mottled with pubescent acne eruptions. “Sorry.”

“That’s better,” Arlo said. “We can’t be fighting with the All-Americans. You gotta be nice to these people. Make it work. For your own good.”

“Totally,” Gertie said. “Should we see what the fuss is all about?”

“No. It’s too hot. Larry and I’d rather sit in the basement and eat paint like sad, neglected babies,” Julia answered. Her normally curly-wild ponytail had gone limp.

“Lead paint tastes sweet! That’s why babies eat it!” Larry announced. “Paint’s not really your option two here,” Arlo answered as Gertie started

for the kitchen, where she grabbed a half-eaten bag of Ruffles potato chips to offer the crowd. Then he leaned over the table, his voice soft. It wasn’t threatening, but it wasn’t not threatening. “There’s no option two. Get the fuck up and slap on some smiles.”

“So, should we go?” Gertie asked.

“’Course!” Arlo answered, his voice soft and nice now that Gertie was back. He opened the front door. The Wilde parents took the lead, then the kids, who followed closely. Maybe it was coincidence, and maybe it wasn’t. But a few feet out, someone switched the music to a song in a minor key. It was “Kennedys in the River,” Arlo’s number-eighteen Billboard hit single from 2012.

Don’t know what love is. Don’t think it matters.

I got sixty dollars.

And a dream that won’t shatter.

Arlo blushed. Hearing his own music was a complicated thing. His family knew this. As a result, Larry and Julia walked slower, like their feet had short shackles between them. Gertie held a smile tight as a zipper. One step after the other, they arrived at Sterling Park.

Sai Singh and Nikita Kaur glanced up from the barbeque. OxyContin- addled Iraq War veteran Peter Benchley ran his fingers along the tender edges of his residual limbs. The gang of kids, self-named the Rat Pack, stopped jumping on the big trampoline someone had wheeled to the center of the park. Shouting something too distant to hear, Shelly Schroeder pointed straight at Julia.

The vibe wasn’t hostile. After all her pageant training, Gertie was good at reading a room and she knew that. But something had changed since the last barbeque, on Memorial Day, because the vibe wasn’t welcoming, either.

She tried to catch Rhea’s eye but Rhea was busy talking to Linda Ottomanelli. There were people everywhere, any of whom she could have approached, but during her time on Maple Street, Gertie’d only ever felt comfortable with Rhea.

You’re heavy under me and above.

Crying in cemeteries like it’s love.

Arlo’s song kept going. Shoulders hunched, the Wildes played captive to a low-class history they couldn’t hide from:

I see my dad in you all sweat and junk.

Baby, run away with me. We’ll shake these blues.

At last, Fred Atlas and his sickly wife, Bethany, picked their slow way through the crowd to greet them. “Dude! You made it!” Fred called as he clapped Arlo on the back. Then they went in for the bro hug. Bethany offered Gertie a winsome smile, her body brittle as a straw man’s. The Atlases’ dog, a rescue German shepherd named Ralph, nudged the whole group of them, trying to keep them safe and in the pack.

“You’re the fijizzle, Fred. You, too, Bethany,” Arlo answered. Then he and Fred took orders and went to the drinks table.

Over by the kids, Dave Harrison disconnected from the Rat Pack. He slid off the trampoline and jogged to Julia and Larry, handing each a sparkler. They lit them and Julia wrote shart in the air while Larry made circles.

“Can I have a burger?” Gertie asked Linda Ottomanelli. On the table were mini American flags on toothpicks, which people had stabbed into their sesame seed buns.

Linda took a second, eyes focused on the burgers, even though it was clear she’d heard. Gertie waited, still and tall. Wondered if she should have worn a shawl over her low-cut dress. But pregnancy was the only time her boobs got to be D cups. It was fun to show them off.

“Cheese or plain?” Linda asked at last.

“Plain? You’re such a trooper to cook in this heat.”

“I can’t help it. I love making people happy. I’m just that kind of person. It could be a hundred and fifty degrees and I’d still do this. It’s my nature. I’m too nice.”

“I noticed that about you,” Gertie offered, which wasn’t true. She’d never noticed much of anything about Linda Ottomanelli, except that she was the kind of woman who wore a fanny pack to the grocery store and who got her politics from the social network. She got the rest of her opinions from Rhea Schroeder, whose word she treated like gospel.

Linda sighed like a martyr. “You must be hungry. I was always hungry when I was pregnant. I mean, I was carrying twins! But maybe you’re not hungry, because you’re so skinny. I hate you for being so skinny! How are you so skinny? You’re like an alien!”

Gertie bit into the burger. Juice ran down her chin and then her cleavage. “I’m just medium skinny if you don’t count the baby. I used to be really skinny, but it’s too hard. You can’t eat bread.”

Linda’s grin flickered.

“One time, I cut out carbs and dairy together, plus I did high-intensity interval training. You could do that if you wanted. I still have some of the books.”

“Thanks,” Linda said.

Over by the trampoline, Julia and Larry started jumping with the rest of the Rat Pack kids, and at the drinks table, Arlo was telling a story to a whole bunch of guys. Something about the clerk at the 7-Eleven who made everybody late for their trains because he was so bad at making change. “I just gave up. I said, ‘Take it, ya rich bastard!’” Arlo drawled, then popped his Parliament Light into the corner of his mouth and made an air fist. His voice was louder than everybody else’s, and they were standing back to get away from the smoke, even Fred.

Pretty soon, everybody was laughing from that first beer or wine, and clapping, and retelling some story from work, or what cute and mischievous thing their kids had done in their kindergarten class that had left the teacher flabbergasted.

The Gradys, Mullers, Pulleyns, and Gluskins were planning a trip to Montauk. Margie and Sally Walsh were explaining how Subarus aren’t really lesbian cars; they’re just practical. The Ponti men compared biceps size. They were in ripping spirits, having come straight from the town baseball league’s end-of-year keg party.

Food and second rounds began. The heat stayed thick. At last, Gertie summoned her courage. She found Rhea Schroeder by her famous German potato salad. The secret ingredient came by way of her mother-in-law from Munich: Miracle Whip.

“Hi,” Gertie said. “I saw you before but I don’t think you saw me. So, hi again!”

Rhea frowned. She’d been doing that a lot lately. Probably, she was stressed out. Between the four kids and the full-time job, who wouldn’t be?

“Has it really been since the spring? I miss our talks.” Gertie willed her eyes to meet Rhea’s. “Want to come over next week? Arlo’ll make his pesto chicken. I know how you like that.”

Rhea seemed to consider, but then: “I’m so busy at work. They can’t spare me. I’m practically holding up the entire English Department. Plus, I’ve been planning things like this. Barbeques. I really don’t have a second.”

Gertie stepped closer, which wasn’t her nature—she liked a wide swath of personal space. But for the sake of this new life she and Arlo were trying so hard to make work, for the sake of her friendship with this smart, funny woman, she pushed past her comfort zone. Her voice quivered. “Did I do something? I know you plan these things. I’m sure it was an accident, that you didn’t invite us?”

Rhea affected surprise. “Accident? No accident at all!” Then she walked, white linen swishing over heels just high enough to keep the grass from staining.

With rod-straight posture and a cement smile, Gertie watched her disappear into the crowd. The party continued. And it was stupid. Pregnancy hormones. But she had to trace her index fingers along her under-eyes to keep the mascara from running.

That’s when it happened.

The music cut to static. The earth rocked. Linda’s red-checked picnic table with all those burgers started to shake. Gertie felt the vibrations from her feet to her teeth.

Early fireworks? . . . Earthquake? Shooter?

There wasn’t time to find out. Gertie did a quick take of the park; met Arlo’s eyes. They fast-walked to the kids from opposite directions. Like magnets, the four snapped together.

“Street?” Gertie asked. “Home!” Arlo shouted.

They hoofed it, running along the thick clovers and dandelions, past the trampoline and hem of pudding stone that bordered the park. With her pregnancy and bad feet, Gertie brought up the rear.

She didn’t see the sinkhole as it opened. Only watched later, from the footage people captured with their phones. What she noticed most was how hungry it seemed. The picnic table and all those burgers fell inside. The barbeque followed. Ralph the German shepherd got away from Fred and Bethany, banking the sink- hole’s lips as they swelled.

A surprised yelp, and Ralph was gone.

By the time Gertie looked back, the hole had reached an uneasy peace with Maple Street. It had stopped growing, leaving just the people. Some had run, some had stayed frozen. Some had even hastened toward that widening gyre, their instincts all messed up.

And then there was Rhea Schroeder. In the stillness, she didn’t turn to her family, whom she’d deftly rescued and corralled to the far side of the sinkhole. She didn’t pet their hair or check in with her spouse like so many others did. She didn’t cry or gawk or take out her phone. No.

She looked straight at Gertie, and bared her teeth.

Between them, a gritty smoke rose up. It carried with it the chemical scent of something unearthed.

SLIP ’N SLIDE

July 5–9

INDEX OF MAPLE STREET’S PERMANENT RESIDENTS AS OF JULY 5, 2027

100 The Gradys—Lenora (47), Mike (45), Kipp (11), Larry (10)

102 VACANT

104 The Singhs-Kaurs—Sai (47), Nikita (36), Pranav (16), Michelle (14),

Sam (13), Sarah (9), John (7)

106 The Pulleyns—Brenda (38), Dan (37), Wallace (8), Roger (6)

108 VACANT

110 The Hestias—Rich (51), Cat (48), Helen (17), Lainee (14)

112 VACANT

114 The Walshes—Sally (49), Margie (46), Charlie (13)

116 The Wildes—Arlo (39), Gertie (31), Julia (12), Larry (8)

118 The Schroeders—Fritz (62), Rhea (53), FJ (19), Shelly (13), Ella (9)

120 The Benchleys—Robert (78), Kate (74), Peter (39)

122 The Cheons—Christina (44), Michael (42), Madison (10)

124 The Harrisons—Timothy (46), Jane (45), Adam (16), Dave (14)

126 The Pontis—Steven (52), Jill (48), Marco (20), Richard (16)

128 The Ottomanellis—Dominick (44), Linda (44), Mark (12), Michael (12)

130 The Atlases—Bethany (37), Fred (30)

132 The Simpsons—Daniel (33), Ellis (33), Kaylee (2), Michelle (2),

Lauren (2)

134 The Caliers—Louis (49), Eva (42), Hugo (24), Anais (22)

TOTAL: 60 PEOPLE

From Newsday, July 5, 2027, page 1

MAPLE STREET SINKHOLE

LONG ISLAND’S DEEPEST spontaneous sinkhole appeared yesterday, this time in Garden City’s Sterling Park during holiday festivities. A German shepherd plummeted inside the 180-foot-deep fissure and has not yet been recovered. No other injuries were reported.

This is the third sinkhole event on Long Island in as many years. Experts warn that more are expected. Accord- ing to Hofstra University geology professor Tom Brymer, “The causes for sinkholes include the continued use of old water mains, excessive depletion of the lowest water table, and increasing periods of flooding and extreme heat.” (See diagram, page 31.)

In conjunction with the New York Department of Agriculture (NYDOA), the New York Environmental Protection Agency (NYEPA) announced yesterday that Long Island’s aquifers have not been affected. Residents may continue to drink tap water.

The NYDOA has closed Sterling Park and its adjoining streets to nonresidential traffic during an excavation and fill, which will begin July 7 and is slated to run through July 18. The nearby Garden City Pool will also be closed. For more on the sinkhole, see pages 2–11.

From “The Lost Children of Maple Street,” by Mark Realmuto,

The New Yorker, October 19, 2037

It’s difficult to imagine that Gertie Wilde and Rhea Schroeder were ever friends. It’s even more ludicrous to think that the friendship would turn so bitter as to result in homicide.

Connolly and Schiff posited in their seminal work on mob mentality, The Human Tide, that Rhea took pity on the Wilde family. She wanted to help them fit in. But a closer look be- lies that theory. When the Cheon, Simpson, and Atlas families moved to Maple Street during the five years prior, Rhea did not attempt the same kinds of friendships. Though she welcomed the families with baskets of chocolate and perfume, by their own accounts, she was cold. “I think she was intimidated,” Christina Cheon admitted. “I’m a doctor. She didn’t like the competition for most accomplished woman on the block.” Ellis Simpson added, “Everybody from around here had family to help them out. That’s why you moved to the suburbs. Free babysitting. I mean, it definitely wasn’t for the culture. But the Wildes were alone. I think that’s why Rhea plugged into Gertie. Bullies seek the vulnerable. You know what else bullies do? They trick people who don’t know any better into believing they’re important.”

It’s entirely possible, then, that Rhea had it out for Gertie from the start.

118 Maple Street

Friday, July 9

“It’s a hairbrush night,” Rhea Schroeder called up the stairs to her daughter Shelly. “Don’t forget to use extra conditioner. I hate that look on your face

She waited at the landing. Heard rustling up there. She had four kids. Three still lived at home. She had a husband, too, only she rarely saw him. It’s unnatural, being the sole grown-up in a house for twenty-plus years. You talk to yourself. You spin.

“You hear me?”

“Yup!” Shelly bellowed back down. “I HEAR you!”

Rhea sat back down at her dining room table. She tried to focus her attention on the Remedial English Composition papers she was supposed to grade. The one on top argued that the release of volcanic ash was the cheapest and smartest solution to global warming. Plus, you’d get all those gorgeous sunsets! Because she taught college, a lot of Maple Street thought she had a glamorous job. These people were wrong. She did not correct them, but they were absolutely, 100 percent wrong.

Rhea pushed the papers away. Sipped from the first glass of Malbec she’d poured for the night, got up, and scanned the mess out her window.

She couldn’t see the sinkhole. It was in the middle of the park, less than a half mile away. But she could see the traffic cones surrounding it, and the trucks full of fill sand, ready to dump. Though work crews had laid down plywood to cover the six-foot-square gape, a viscous slurry had surfaced, caking its edges. The slurry was a fossil fuel called bitumen, found in deep pockets all over Long Island. It threaded outward in slender seams and was mostly contained within the park, but in places had reached under the sidewalks, bubbling up on neighbors’ lawns. There was a scientific explanation, something about polarity and metal content. Global warming and cooked earth. She couldn’t remember exactly, but the factors that made the sinkhole had also galvanized Long Island’s bitumen to coalesce in this one spot.

All that to say, Sterling Park looked like an oozing wound.

They never did find the German shepherd. Their theory was that a strong current in the freshwater aquifer down there had carried him away. They’d likened it to falling through ice in a frozen pond, and trying to swim your way back to the opening.

He could be anywhere. Even below her feet. Funny to think.

This evening, the crescent was especially quiet. Several families had left town for vacations or to get away from the candy apple fumes. Those who remained, if they were home at all, stayed inside.

Just then, pretty Gertie Wilde emerged from 116’s garage. She carried a haphazardly coiled garden hose, its extra slack spilling down like herniated intestines. Gertie’s big hair was coiffed, her metallic silver eye shadow so glistening that Rhea could see it from a hundred feet away. She stopped when she got to the front yard, hose in hand.

Rhea’s pulse jogged.

Gertie peered inside Rhea’s house, right where Rhea was standing. She seemed frightened and small out there, like a kid holding a broken toy, and suddenly, Rhea understood—Gertie had no outdoor spigot to which to attach her hose. She needed to borrow. But because of the way Rhea had acted at the Fourth of July barbeque, she was afraid to ask.

A thrill rose in Rhea’s chest.

Margie Walsh screwed it up. She came out from the house on the other side of Gertie’s and walked fast to meet her. Waves and smiles. Rhea didn’t hear the small talk, but she saw their laughter. Polite at first, and then relaxed. They hooked the hose, then unrolled a plastic yellow bundle, running it the length of the Walsh and Wilde lawns. Water gushed and sprayed. A Slip ’N Slide. With the temperature lingering at 108 degrees, its water emerged like an oasis in a desert.

Pretty soon, Margie’s and Gertie’s kids came out. Fearless Julia Wilde gave herself ten feet of running buildup, then threw herself against the plastic and slidall the way down until she landed on grass. Charlie Walsh followed. Each took a few turns before they could convince rigid Larry. At last, he did it, too. But Larry, uncoordinated and holding Robot Boy, didn’t build enough momentum. Only slid halfway.

The lawn got torn up. The kids got covered in mud and then hosed themselves off and started over. Tar from the sinkhole stuck to their clothes and skin like Dalmatian motley.

Now that the seal was broken, all of Maple Street opened up and shook loose. The rest of the Rat Pack and some of their parents streamed out. Laughter turned to screams of delight as even the grown-ups joined in.

Rhea watched through her window. The laughter and screams were loud enough that muffled versions of them permeated the glass.

Gertie didn’t know any better. With her central air-conditioning broken, she’d probably gotten used to that slightly sweet chemical scent. The rest of them were stir-crazy. Figured, if a pregnant woman was willing to take the risk, the rest of them were pansies not to go out, too.

But anybody who watches decent science fiction knows that the EPA isn’t perfect. The stuff her neighbors were rolling around in tonight might glue their lungs with emphysema twenty years from now. Even her husband, Fritz, who never had an opinion about anything domestic, had announced that if the hole didn’t get filled like it was supposed to, they ought to pack the family into a short-term rental. He’d crinkled his nose that very first night it happened, grudging fear in his eyes, and said, “When it smells like this in the lab, we turn on the ventilation hoods and leave the room.”

Rhea ought to warn these people. She was obliged, for their safety. But if she did that, they’d think she was a killjoy. They’d think it had to do with Gertie.

She played the conversation out in her head. She’d go out to 116, trespassing on Gertie’s property, and urge them to go home. To take hot showers with strong soap. They’d put down their beers, nod in earnest agreement, wait for her to go away, and then start having fun again. Probably, they wouldn’t say anything mean about her once she was gone. Not openly. But she knew the people of Maple Street. They’d chuckle.

She backed away from her window.

Returned to her papers. Sipped a little more Malbec as she reviewed the next assignment in the pile, which was written in 7-point, Old English font. It was about how the last stolen election had proven that democracy didn’t work. We needed to move into Fascism, only without the Nazis, the student argued. She took out her red pen. Wrote, What???? Nazis = Fascism; they’re like chocolate and peanut butter!

Between the papers, the people outside, her husband at work, and even her children upstairs, Rhea felt very alone right then. Misunderstood and too smart for this world. All the while, Slip ’N Slide laughter surrounded the house. It pushed against the stone and wood and glass. She wished she could let it in.

…

Like so many people who find themselves on the far side of middle age, Rhea Schroeder had not expected her life to turn out this way. She’d grown up only a few miles away in Suffolk County, the daughter of a court officer. Her mom died young, of breast cancer, and her dad had been the strong, silent type. He’d loved her enough for two parents. They’d shared an obsession with science fiction, and what she remembered most about him was the hours they’d spent on the couch together, watching everything from The Day of the Triffids to the poor man’s 2001—The Black Hole.

As a kid, friends hadn’t come easily for Rhea, but school had. She’d been the first in her family to graduate college—SUNY Old Westbury. Her first job out had been retail at the mall, like everyone else. Through connections, her dad got her into the officer’s academy. Too many personalities. Too much phys ed. She didn’t want to be a cop. She dropped out, floundered for a while, then stopped her dad one night before he headed down to tinker in his workroom. Told him about this PhD program in Seattle. People expressed themselves through im- perceptible signs, she’d explained. She wanted to translate them. She wanted to solve the puzzle of what made people tick. Her dad was understanding. Hugged her and said he’d been selfish, suggesting detective work on Long Island because it was close. He hadn’t wanted to lose her.

She’d been sad to leave him on his lonesome. But excited, too. Her life be- came her own. Five years later, the University of Washington awarded her a PhD in literature, with a focus in semiotics. Then they hired her, tenure track. The work was great. The students were great. The teachers were great. It was the happiest she’d ever been.

But then she got a phone call. Her dad died suddenly, of a disease she’d never imagined. Would never have suspected. In the shock of it, her work downslid. Her sadness felt impossibly heavy, a physical accumulation that she couldn’t expunge. A knotty weight inside her that she came to think of as the murk.

Before her dad died, she’d never felt the need for other people. Never understood the phoniness of passing notes with fellow third-grade girls, or the high school version of it: trading clothes. Who were they kidding with all that desperate posturing? Those friendships weren’t real. In adulthood, the women her own age had seemed so alien, with their bad jobs and insecurity. She’d stayed away from them, afraid low self-esteem was contagious.

But after her dad, she’d had nobody to call on Sundays and remote-watch Solaris with. Nobody to visit over holidays, or shoot clay pigeons with at the Calverton Shooting Range. They’d had something easy and perfect between them. A stillness, into which no words had ever been necessary.

Seeking relief from her empty apartment, the blank page that was meant to be a book based on her dissertation, she started taking her students out for coffees and beers after class. Their cheerful passion distracted her. Made time pass a little easier.

By the next semester, she was starting to feel like herself again. Waking up wasn’t as scary, because the memory of his passage didn’t suddenly grab her like undertow at an ocean. She was starting to actually become friends with her students and the faculty, too. The murk lifted.

That’s when the accident happened. A totally unforeseen, random event. Through no fault of her own, she wound up with a sprained knee. To this day, it ached in bad weather. The other person got hurt even worse. An accusation was lodged. False, but damning nonetheless. Rhea got demoted, which, in academia, is the same as being fired. And that was that. A stellar career, destroyed.

Her life got even emptier. No more coffees. No more beers. School and home and school and home. She felt bad about the accident. It was a terrible mistake that her mind wanted badly to undo.

That’s when fate stepped in. Fritz Schroeder, a German chemistry PhD ten years her senior, moved into her apartment complex. He knocked, asking if she knew how to use the cheap convection ovens provided in each kitchen. Wearing a pink polo shirt with the collar pulled up, his khakis stained at the knees with brown chemical from the lab, he’d looked lonely. Helpless. Something about him was broken.

“Let’s look it up!” she’d said, because at the time, she hadn’t known how to use an oven, either.

A boyfriend hadn’t been a part of her plan. She’d always pictured her future as an empty room, clean and bright; filled only with ideas and the long-distance adoration of colleagues. She hadn’t imagined sharing her time with anyone but her dad. Not when she had so much important work to do.

But plans change. Careers crash and burn. She’d been so lost. Then along came Fritz: a brain in a box with occasional human urges. Unobtrusive but breathing. The perfect choice.

As a person, he had peccadilloes. He needed his shoes to be arranged in specific directions, and he couldn’t stand tags in his shirts, and he had an earwax buildup problem, except he hated the sensation of Q-tips, so he used steamed washcloths. He ate whatever random items he found in her cabinets, including tuna out of the can with his fingers. It grossed her out so much that she learned to cook. When she bought clothes for herself, she bought new khakis and tagless shirts for him, too. It’s nice to do things for other people, especially when they return the favor with wide-eyed gratitude. Besides, she’d had plenty of peccadil- loes of her own. She’d just been better at hiding them.

About a year into dating, Fritz accepted a high-paying job formulating per- fumes at the BeachCo Laboratories in Suffolk County. Sugary-smelling stuff with names like Raspberry Seduction and French Silk for the low-end Duane Reade market. She’d suggested marriage, even though she’d known that it wasn’t right between them. They weren’t close in an emotional way. Didn’t confide in each other or talk about their upbringings. For instance, he had no idea about The Black Hole, or the murk, or the accident that had ruined her career.

Still, one evening he took her to the top of the Space Needle. Led her to the edge. “Even around people, I always feel separate,” he’d explained without looking her in the eyes. “I’m lonely with you, too.”

Her gag reflex had triggered. Was he dumping her? Didn’t he know that without him, she had nothing? She’d seen him standing there, looking scared, and it had taken a great effort of self-control not to shove him right off the ledge.

He took the small, princess-cut ring out of his pocket. “But you take care of me. No one’s ever done that. I’m a limited person. I think this is the best it will get,” he’d said. “And I do love you.”

“You know?” she’d answered with total surprise. “I think I love you, too.” By then, tourists were watching, clapping. So they’d kissed.

The wedding was at the justice of the peace. No honeymoon. Just a flight to Long Island. She never got around to unpacking the box that contained the pieces of her unfinished book, because by then, she’d been pregnant with Gretchen.

In her pre-Fritz life, she’d debated abstruse theory with Ivy League geniuses. Now, she spent her days on Maple Street, alone with babies. These babies often cried. Sometimes she didn’t know why. She didn’t speak baby. It got hard. All that stuff she’d always thought was stupid, destructive female fantasia—stuff like friends and hugging and hot sex—she found herself watching Terminator and Starman and The Abyss, wishing she had it. Wondering what was wrong with her, that she didn’t.

Fritz spent the time building his career. He only showed up on weekends and when his family visited from Munich. When he and Rhea were together, they cheered soccer games and dropped kids at the mall and paid bills in perfect agreement; partners who know each other like the lines of their own hands. But it was all surface. No laughs, no confidences, no companionship.

It was so lonely.

The first ten years, she cried a lot. But she kept it a secret, a hidden shame, because she was sure that her lackluster marriage was evidence of her own inadequacy. If she confessed her loneliness to Fritz, he’d know the truth: that she was messed up. He’d divorce her. His lawyer would unearth the accident. Everyone would know why she’d been fired from U-Dub. All of Maple Street. They’d look at her and see right through her. They’d know everything. Unthinkable.

And so, she dried her eyes. She buried her loneliness so deeply that she lost the knowledge of it. She stopped seeing it.

The following decade, she transformed herself into everything a suburban wife and mother ought to be. She organized all the block parties and made it her business to befriend every new addition to Maple Street with a basket of chocolate goodies and Fritz’s newest perfume. She volunteered at the kids’ schools and raised funds for iPads and art teachers. She resolved arguments and reported bullies. She sent out annual family Christmas cards with the Schroeders in matching sweaters, adopted class crayfish, and stayed up late most nights with her daughters, because one of them invariably had a crisis.

She worried about Gretchen’s perfectionism, and Fritz Jr.’s shyness that he used to medicate with food and now he medicated with other things. About Shelly’s instability, and Ella’s stutter, which had since resolved. Four kids is a lot. But she did it well. She raised them popular and healthy and smart. Teachers complimented her. So did neighbors. She dressed like she was supposed to, in Eileen Fisher, and she cooked nutritious foods, and she kept her figure accept- ably trim. She looked the part until she felt the part. Until she was the part.

Once her youngest started grammar school, she picked up work as an adjunct professor, teaching English Composition at Nassau Community College—the only job she’d been able to get after the stain on her record.

Mostly, these things were enough. But occasionally, the murk unfurled. She’d spy her reflection in a mirror when she was alone, mid-argument with an imaginary enemy (and there was always some jerk she was mad at), or else brushing Shelly’s hair, and think: Who is that angry woman?

It frightened her.

When her oldest left for Cornell University last year, she’d taken it hard. She’d been happy for Gretchen, but her brilliant future had made Rhea’s seem that much more dim. What was left, once all the kids were gone away, and she was left with a thirty-year-old dissertation and Fritz Sr., Captain Earwax Extraordinaire? She’d wanted to break her life, just to escape it. Drive her car into the Atlantic Ocean. Take a dump on her boss’s desk. Straddle her clueless husband, who’d never once taken her dancing, and shout: Who cleans their ears with a washcloth? It’s disgusting! She’d wanted to fashion a slingshot and make a target range of Maple Street, just to set herself free of these small, stupid people and their small, stupid worlds.

It would have happened. She’d been close to breaking, to losing everything. But just like when Fritz moved into her apartment complex: fate intervened. The Wildes moved next door. Rhea couldn’t explain what happened the day she first saw Gertie, except that it was magic. Another outsider. A beautiful misfit. Gertie’d been so impressed by Rhea. You’re so smart and warm, she’d said the first day they’d met. You’re such a success. Rhea’d known then, that if there was anyone on Maple Street to whom she could reveal her true feelings, it was this naïf. One way or another, Gertie Wilde would be her salvation.

Rhea had courted Gertie with dinner invitations, park barbeques, and intro- ductions to neighbors. Made their children play together, so that the Rat Pack accepted the new kids on the block. It wasn’t easy to turn local sentiment in Gertie’s favor. The woman’s house wasn’t ever clean or neat. A pinworm outbreak coincided with their arrival, which couldn’t have been a coincidence. The whole block was itching for weeks.

Worse, her foulmouthed kids ran wild. Larry was a hypersensitive nutbar who carried a doll and walked in circles. Then there was Julia. When they first moved in, she stole a pack of Parliaments from her dad and showed the rest of the kids how to smoke. When her parents caught her, they made her go with them door to door, explaining what had happened to all the Rat Pack parents. Rhea had felt sorry for crying, confused Julia. Why make a kid go through all that? A simple e-mail authored by Gertie stating the facts of the event would have sufficed—if that!

It’s never a good idea to admit guilt in the suburbs. It’s too concrete. You say the words I’m sorry, and people hold on to it and don’t let go. It’s far better to pave over with vagaries. Obfuscate guilt wherever it exists.

The sight of all the Wildes in their doorways had added more melodrama than necessary. The neighbors, feeling the social pressure to react, to prove their fitness as parents, matched that melodrama. Dumb Linda took her twins to the doctor to check for lung damage. The Hestias wondered if they should report the Wildes to Child Protective Services. The Walshes enrolled Charlie in a health course called Our Bodies: Our Responsibility. Cat Hestia had stood in that doorway and cried, explaining that she wasn’t mad at Julia, just disappointed. Because she’d hoped this day would never come. Toxic cigarettes! They have arsenic!

None of them seemed to understand that this had nothing to do with smoking. Julia had stolen those cigarettes to win the Rat Pack over. A bid toward friendship. She’d misjudged her audience. This wasn’t deep Brooklyn. Cool for these kids meant gifted programs and Suzuki lessons. The only people who smoked Parliaments anymore were ex-cons, hookers, and apparently, the new neighbors in 116. What she’d misapprehended, and what the Wilde parents had also missed, was that it wasn’t the health hazards that bothered the people of Maple Street. If that were the case, they wouldn’t be Slip ’N Sliding right now. It was the fact that smoking is so totally low class.

Despite all that, Rhea had stuck by Gertie Wilde until, one by one, the rest of Maple Street capitulated. It was nice, doing something for someone else, especially someone as beautiful as Gertie. There’s a kind of reflective glow, when you have a friend like that. When you stand close, you can see yourself in their perfect eyes.

At least once a month, they’d drunk wine on Rhea’s enclosed porch, cracking jokes about poop, the wacky stuff kids say!, and helpless husbands whose moods turn crabby unless they get their weekly blowies. This latter part, Rhea just pre- tended. She accepted Fritz’s infrequent appeals for missionary-style sex, but even in their dating days, their mouths had rarely played a part, not even to kiss.

Rhea’s attentions were rewarded. Eventually, Gertie let down her guard. Tears in her eyes, voice low, she’d confessed the thing that haunted her most: The first, I was just thirteen. He ran the pageant and my stepmom said I had to, so I could win rent money. He told me he loved me after, but I knew it wasn’t true. After that, I never said no. I kept thinking every time was a new chance to make the first time right. I’d turn it around and make one of them love me. Be nice to me and take care of me. So I wouldn’t have to live with my stepmom. But that never happened. Not until Arlo. I’m so grateful to him.

When she finished her confession, Gertie’d visibly deflated, her burden lightened. Rhea had understood then why people need friends. They need to be seen and known, and accepted nonetheless. Oh, how she’d craved that unburdening. How she’d feared it, too.

They built so much trust between them that one night, amidst the distant catcalls of children gone savage, Rhea took a sloppy risk, and told her own truth:

Fritz boom-booms me. It hurts and I’ve never once liked it . . . Do you like it? I never expected this to be my life. Did you expect this, Gertie? Do you like it? I can tell that you don’t. I wanted to be your friend from the second I saw you. I’m not beautiful like you, but I’m special on the inside. I know about black holes. I can tell you want to run away. I do, too. We can give each other courage . . . Shelly can’t keep her hair neat. It goads me. I’d like to talk about it with you, because I know you like Shelly. I know you like me. I know you won’t judge. Sometimes I imagine I’m a giant. I squeeze my whole family into pulp. I wish them dead just so I can be free. I can’t leave them. I’m their mother. I’m not allowed to leave them. So I hate them. Isn’t that awful? God, aren’t I a monster?

She stopped talking once she’d noticed Gertie’s teary-eyed horror. “Don’t talk like that. You’ll break your own house.”

There’d been more words after that. Pleasantries and a changed subject. Rhea didn’t remember. The event compressed into murk and sank down inside her, a smeared oblivion of rage.

Soon after that night, Gertie announced her pregnancy. The doctor told her she had to stop drinking front-porch Malbec, so they hung out a lot less. She got busier with work and the kids and she’d played it off like coincidence, but Rhea had known the truth: she’d shown her true self, and Gertie wanted no part of it. Retaliation was necessary. Rhea stopped waving at Gertie when she saw her, stopped returning her texts. When that didn’t make her feel any better, when oblivious Gertie didn’t even notice her coldness at the Memorial Day barbeque, she bit harder. She told people about Arlo’s heroin problem. How that was the reason for the tattoos covering both his arms. He was trying to hide the scars. She told about Gertie and all those men. Practically a hooker. She told every-

thing, to anybody who’d listen.

The more she told those stories, the more the past kaleidoscoped. She re-evaluated every interaction she’d ever had with Gertie and her family, every judgment she’d ever cast.

For instance, Arlo yelled. His voice boomed. You could see Larry, who was sound-sensitive, shrink inside himself when that happened. But Arlo never checked himself. He just kept shouting, like he didn’t care that he was hurt- ing his own kid. What was even more alarming, Gertie had all kinds of rules. Unless it was baking hot, Julia couldn’t wear short sleeves and shorts together because they revealed too much skin. No bikinis, ever. If she changed clothes on playdates, she had to do it in the bathroom. She couldn’t walk to the bus stop by herself, or even with Shelly. A grown-up had to accompany. Why was she so nervous? What did she know about sexual threats on Maple Street that no one else knew?

In other words, why was Larry always jerking himself?

Here’s a story: One time, Rhea, Fritz, and the kids were at the Wildes’ for dinner. It was its usual mess. Greasy dishes and thumbprints on the wineglasses. So Rhea’d washed while Arlo had cut vegetables, and Gertie had poached eggs. Even Fritz had helped out; for maybe the first time ever, he’d set the table. Until then, she’d never have guessed he knew how!

They’d all had so much fun and felt so close. On their way out the door, saying their good-byes, Arlo had leaned into Rhea, hugging her a beat too long. “Thanks for being so good to Gertie,” he’d said, and then he’d kissed her cheek but gotten the corner of her lips, too. Dazed, she’d looked to Gertie to see if her friend was jealous, only Gertie’d acted like it was nothing.

At the time, Rhea’d felt flattered. But later she’d wondered: Had Arlo been hit- ting on her? And if a wife can ignore something like that, what else can she ignore? She’d related her observations to Linda Ottomanelli, who, most likely, had spread it around to the rest of the neighbors. And then, last week, she’d been planning the barbeque, and she’d known that if Gertie and her family showed up, that the neighbors might ask questions, compare stories. If Gertie found out about the rumors Rhea had spread, she might get mad enough to retaliate.

Spill beans she had no business spilling. So she’d eliminated the problem, and excluded the Wildes.

The exclusion didn’t feel cruel. It felt like self-preservation. And if the murk had unfurled again, more rage-filled than ever, at least she’d found the proper target against whom to direct it.

Order Now

Welcome to Maple Street, a picture-perfect slice of suburban Long Island, its residents bound by their children, their work, and their illusion of safety in a rapidly changing world.

Arlo Wilde, a gruff has-been rock star who’s got nothing to show for his fame but track marks, is always two steps behind the other dads. His wife, beautiful ex-pageant queen Gertie, feels socially ostracized and adrift. Spunky preteen Julie curses like a sailor and her kid brother Larry is called “Robot Boy” by the kids on the block.

Their next-door neighbor and Maple Street’s Queen Bee, Rhea Schroeder—a lonely community college professor repressing her own dark past—welcomes Gertie and family into the fold. Then, during one spritzer-fueled summer evening, the new best friends share too much, too soon.

As tensions mount, a sinkhole opens in a nearby park, and Rhea’s daughter Shelly falls inside. The search for Shelly brings a shocking accusation against the Wildes that spins out of control. Suddenly, it is one mom’s word against the other’s in a court of public opinion that can end only in blood.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use