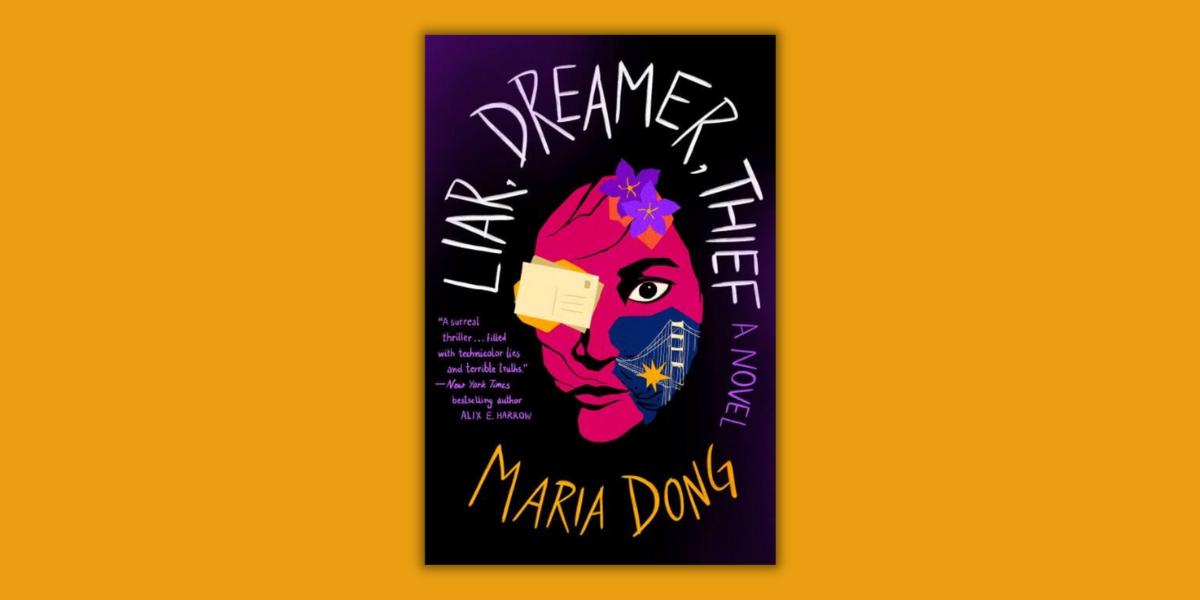

Read the Excerpt: Liar, Dreamer, Thief by Maria Dong

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

This Is Your Stop

I am on the phone with Leoni, who is technically my roommate, though she’s out of town for months at a time due to her career as a traveling occupational therapist—mostly working in nursing homes, helping people relearn how to get dressed and bathe and put on hellaciously compressive stockings.

Her absence suits me just fine. The long stretches between our actual cohabitations are probably also our salvation, because even though there’s no reason for us not to get along, I have a tendency to hate people I spend too much time with, and I’ve been told I’m not a very good friend, despite my best efforts.

I guess I’m saying I have a habit of getting on everyone’s nerves—which is why I’m desperately fighting the urge to tell Leoni about my coworker Kurt’s new book. My fascination with Kurt is her biggest pet peeve, and she’s put me on notice more than once.

Kurt never takes his lunch in the break room. Instead, no matter how cold it is, he grabs his briefcase and his latest incredibly-expensive-looking phone and walks to his car in the company parking structure. Sometimes, I follow him at a distance, trying to catch a glimpse, but I usually use the opportunity to stroll by his desk and look for clues as to what makes him tick. He always keeps his current book in the second drawer from the bottom, and if he’s in a hurry, he doesn’t shut it all the way, which is how I’ve learned that he mostly reads history books: military strategy, secret orders, codes, mythical creatures. He never talks about history, though, and he’s never seemed like the kind of person who would buy into conspiracy theories.

If I can get the title of the book and the author’s name without attracting the attention of any neighboring coworkers, I write it on a yellow sticky note to look up when I get home—reviews, articles, Goodreads listings—collecting tasty facts with which I can engineer a greater understanding of the man known as Kurt Smith.

Leoni hates my interest in Kurt, which is why I try not to bring it up. But she’s been droning on about how the pregnant woman she was temporarily hired to replace might come back early, and how much she dreads talking to her recruiter at the staffing company.

“I swear to god, if I have to call him again about my stipend and hear porn in the background, I’m going to switch companies—”

Normally, I’m grateful for Leoni’s ability to keep a conversation going by herself, but on the phone, it’s hard to stay in the moment. And when I get bored, I lose sight of what’s around me, like the water-stained walls of my apartment or the half-closed, weeks-old pizza box on the coffee table I can’t seem to manage to throw out.

Instead, I’m tempted to peer into my version of the kitchen-door world—to watch the sands shift on the Beaches Strange and Wild, to immerse myself in the songs of the Enchanted Forest That Shimmers as It Sings, to witness the spectacle of hundreds of anthropomorphic once-travelers slumbering on moss as dragonflies wind their way through the breathy, fluting strains of music I’ve only heard in my mind.

My favorite thing to do, though, is to look for people’s analogues—to observe how my mind represents real people from my life in the kitchen-door world.

Not every person or place has an analogue, but important ones do, and they never change. Our apartment, for example, transforms into the hut Mi-Hee found when she first made it across the Beaches Strange and Wild: a stinking, one-room hovel with a leaky, thatched roof and crumbling walls covered in mold. It looked abandoned, and Mi-Hee needed a place to hide from the weather.

It wasn’t until the middle of the night that she realized it was full of ghosts.

The surrounding apartments in my building are also huts, though they are better maintained, save for our neighbor Mrs. Marple’s. I usually imagine her analogue as a robed grim reaper with a scythe, and her army of cats as a flock of tiny demons, each begging for tributes of human flesh. Grim reapers aren’t canonical to Mi-Hee’s kitchen-door world, so I’m not sure how they ended up in mine—although ever since I realized the book I read was a bad translation, I’ve wondered how much my kitchen-door world actually reflects Mi-Hee’s.

Leoni’s always a unicorn, which makes her analogue a shapeshifter, though she’s not nearly as brutal as the unicorns in the Vicious Valley, which spear liars and evildoers through the heart with their horns before ripping their bodies apart. When I imagine Leoni in her equine version, she’s the color of a pearl, with a long, flowing mane. Her human form in the kitchen-door world just looks like herself: a white girl just a bit taller and slimmer than average, with the kind of bleached pixie cut I wish I could pull off. She says it’s for her job, that long hair can get caught or pulled when you’re transferring patients, but I can’t help but think it makes her look like an early-aughts pop star.

Kitchen-door analogues always feel random, at first, but once I get to know the person or place better, I always learn there’s something that connects them to their analogue. Leoni’s temperament is a lot like the unicorns Mi-Hee encountered, which have a dual personality: so soft and kind they float across the grass without bending it, but carnivorous and bloodthirsty when threatened.

In a way, it’s always made me trust Leoni more. She’s unpredictable, until you understand her analogue.

I resolved a few days ago to no longer give in to the temptation of the kitchen-door world, even if my visits make me feel like I under- stand my own life better. I’ve known all along that carrying around an imaginary realm as a grown woman isn’t healthy, but it used to seem innocuous and fun—like scoping out an ex’s social media.

The strength of the visualizations has grown over time, though, as has my need to indulge in them whenever I’m stressed, bored, or just curious. Lately, it’s become compulsive and frantic—like finding out the ex you’re still in love with is dating someone new, and if you don’t figure out how this person stole them away from you, you’ll be doomed to an aching loneliness for the rest of your life.

It doesn’t matter that it’s bad for me, that the short-lived relief from the kitchen-door world can’t compete with the shame of needing it in the first place. It doesn’t even matter that I’m not always in control— that the kitchen-door world can overtake me through no choice of my own, that I can’t always tell what’s real and what isn’t. No matter what, I’m always just a breath away from slipping beneath its surface, from seeing and hearing the fantastic overlaid on everything around me.

The urge builds. If I looked into the kitchen-door world right now, Leoni would probably be in her human form—the swoops of her somehow always perfect eyeliner, a puckered red scar on her forehead to replace her horn. Before long, whispers trickle into the corners of my hearing, the rustle of a soft wind that hums with the wings of dragonflies.

There are too many things I want right now—to see her analogue, to tell her about Kurt, to hang up the phone—and the pressure of these desires is like the stretching over a pimple, the tension of an overflow- ing cup. Something has to give.

I blurt it out before I can stop myself. “Kurt’s reading a new book. One about medieval demons.”

“That’s fucking weird,” she snaps. It’s almost cruel, the way she says it, like a child’s condemnation on the playground.

“It’s not that weird.” I somehow don’t sound as defensive as I feel. “People have lots of interests—”

“You know what I mean. You need to stop doing that.” I can hear something in the background, a soft, mechanical hum like a fan, only more rhythmic. An air conditioner? Road noise? Or is it the music that emanates from the Enchanted Forest That Shimmers as It Sings?

“It was funny, at first. But you’re really becoming a stalker.”

As wounds go, this one’s deep. “I’m not a stalker.” It’s an amazing lie, because I believe it, despite knowing most people would disagree. The truth is that I do follow Kurt around, and I pay attention—I can tell you the books he reads, the music he listens to, that he has arugula-filled salads for lunch four days a week and treats himself to a sub sandwich on Fridays. That he always answers the phone with “Go for Kurt” and not “Hello”; that on summer weekends he takes his boat out on the water and forgets to put sunscreen on the tip of his nose, which burns so much faster than the rest of him; that his hair always smells faintly of pears. That sometimes, when he thinks nobody is looking, his face changes, the expressions melting off like wax, reveal- ing something as hard and unreadable as concrete, like there’s an entirely different man under his skin. It reminds me of those white Greco-Roman statues, the way archaeologists recently discovered they were all once covered in garish paints—a secret, unless you know where to look.

I haven’t been able to figure out where Kurt lives yet, because like I said, I’m not really a stalker. I don’t break a bunch of laws in my quest to discover new things—but I’ve assembled enough clues in three years of following him around to know a lot about his inner world.

Like his deepest secret. I know that because it’s hidden in a box on my shelf.

“I’m not here to judge,” Leoni says. I have no idea how much time has passed since I last spoke. The hum gets louder.

“It’s just because it’s boring at Advancex.” This is another lie-not-lie. Yes, work is boring, but that’s not why I can’t stop seeking out Kurt.

I don’t know why I can’t stop.

“I know. But still, you could get in trouble. And he’s not really that interesting, anyways. I’d rather just hear about you. How are things at Advance-sex?” She makes her voice light, leaning on the pun that’s sent us giggling on quite a few wine nights—how, how could a Fortune 500 company not realize customers would see “Advancex” and think Advance‐sex instead of Advance‐ex?

“They’re okay.” I know I’m supposed to elaborate, but no matter how much I flail, there’s nothing else I can tell her—nothing happen- ing in my life that isn’t related to Kurt or the kitchen-door world.

She clears her throat. “Listen…I’m starting to worry about you, you know.”

“There’s nothing to worry—”

“It’s not just this Kurt business, although that’s part of it. How has . . . have you still been seeing things?”

My throat closes up, but I manage to give her my best approximation of an exasperated sigh. “God, Leoni. We were both drunk. I was making it up—”

“I’ve seen you, though. At least with the numbers. Counting your steps, that kind of thing. Do you think—”

“There’s nothing wrong with me!” It’s sharp enough that I can hear her pull the phone away from her ear, and I take a deep breath. “I don’t think I’m Jesus, or that I can fly. I’m not washing my hands until they bleed. And nobody sends me secret messages over the radio.” All lame jokes, and I can tell from the silence between us that they land like frying pans.

Another pause. “Maybe you’re right, and you confessing to seeing a fantasy world around you—that you sometimes can’t tell what’s imaginary—maybe that was all drunk talk. Or maybe, you should consider seeing someone. Really, it couldn’t hurt.”

“Right,” I say, though she’s wrong. It can hurt. Therapy isn’t magic, and the wrong therapist can do more harm than good. “I’ll think it over, okay?” The edges of the world around me are starting to feel wavery, a sign of the kitchen-door world pressing in. This conversation is making me too upset. I have to get off the phone.

“Either way, you should stay away from Kurt. You don’t really know him, not the way you think you do—”

“Hey, someone’s calling. I’ve got to go.” I hang up before she can answer, but it’s too late. When I turn around, there’s a miniature forest of enchanted mushrooms growing in my kitchen, populated by drag- onflies that dart back and forth, their bellies shining with the lights of the tiny fairy lanterns they carry. The entire room is cast in a soft purple glow, which I know is actually white and emanating from the hood lamp over the stove—but my eyes don’t see it, and after a few moments, I’m no longer sure. Is the light purple or white? Am I in my kitchen, the Enchanted Forest That Shimmers as It Sings—or both?

I close my eyes hard and count to eleven, focusing on the numbers, the way they feel as they take up space in my brain. With each one, the urge to slide into the kitchen-door world ebbs. When I’m finally brave enough to look again, the forest is gone, all save a single flower: a purple, five-pointed star that sits atop a woody stem so long it almost reaches my thigh.

I swallow. It’s a doraji—a perennial flower used in Korean medicine, though the roots are also frequently eaten: with rice, as a seasoned vegetable, as liquor or candy or tea. In English, they’re commonly referred to as “balloon flowers” for the puffy appearance of the buds before they open, though my mom always preferred their other name: bellflowers.

She brought the seeds with her when she first emigrated from Busan. She tended them until they took over half the backyard, a thicket of blue-purple flowers cheerfully impervious to the cold winters of Pleasance Village, Illinois.

Doraji weren’t described in Mi‐Hee and the Mirror‐Man. That isn’t to say they weren’t there—it was a Korean children’s book, after all—but what does it mean that after almost three years of seeing the book’s imaginary forest in my kitchen, there’s suddenly something new to find?

Though I know the flower isn’t real, I can’t help extending a finger toward it. Right before I brush the velvet of its petals, it shimmers into nothing.

When I said Mi-Hee’s spyglass revealed the truth, I didn’t mean facts, because people cannot be understood by their facts alone. I’ll prove this later, but for now, here are mine:

Once upon a time, I was on scholarship in music school, after somehow nailing the audition on my clarinet—a life choice my high-school band director of a father had warned me against many times, because music isn’t a career, not really, and no matter how much he actually loved his job, he didn’t want me to end up like him, sublimating his artistic desires to teach a passel of horny asshole teenagers—though I, at least, would never feel the burden of white suburban parents bent on the Ivies pretending they didn’t understand my accent.

And maybe my mental health was the best, and maybe it wasn’t, but what I can tell you is that I was good—good enough that my sophomore year, I was selected for soloist on a performance of K. 622, Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in A Major. I’d aced the audition, in no small part because the K. 622 was one of my father’s favorite pieces. The bouncy, mellifluous runs of notes that glide carelessly through the full range of the instrument, the way it’d been published posthumously without an autograph to explain how Mozart had wanted it to be performed. Musical historians can’t even agree on the exact instrument it’d been made for: the basset horn, the A clarinet, or the basset clarinet, none of which are common members of modern classical ensembles.

By then, my parents had already started pulling away and weren’t returning a lot of my calls. When they did, they always seemed distracted, as if there was something else they’d rather do. They’d assured me they would attend my performance, though—but when I sat there bathed in the bright lights, scanning the shadowy impressions of the audience for their silhouettes, I couldn’t find them.

It was like my muscles just solidified—my fingers, my tongue, my guts. I couldn’t move, and everything was going wavy. I managed to pull it together and blow into the mouthpiece, but it wasn’t notes—just squawks. There I was, onstage in front of a packed auditorium, honk- ing like a goose.

I ran offstage. Threw up. Skipped class—weeks, then months— and then nobody paid the measly tuition bill that was left over after my scholarships had been applied. When they evicted me from the dorms, I went to my parents’ house, but my father wouldn’t let me in. We stood there on the porch, a mist of sleet quietly falling around us, until he handed me his keys. “Go to a hotel or a friend’s house,” he said. “We can talk about this later.”

Maybe things would have turned out differently if I’d confessed to failing out of college, to losing my scholarship. If I’d screamed at him about the bill. If I hadn’t lied about having money, lied about having friends.

I took their car to the Pleasance Sunbeam Library. I knew from a thousand childhood visits that it wasn’t open on Sundays, that it has a small employee lot around the back that’s obscured from the main road. I slept there that night, in the back seat of my parents’ car, my breath fogging the inside of the windshield as the evening cooled, eventually turning to frost. When I woke shivering at dawn and looked out, I didn’t see anything through the ice but soft shapes—and then I closed my eyes, and there it was, a door hanging in the corner of my mind, one I hadn’t seen since I was a child and obsessed with a book about a girl and a spyglass. I saw myself stepping through, and for a moment, everything smelled like smoke.

I turned the car on and let the engine warm. I scraped the ice—on the outside, on the inside, the legacy of my frozen breath—until there was a hole large enough to see. And then I pulled onto the highway and drove the two and a half hours to the big city, to Grand Station, Illinois, thinking I’d make a new life for myself, one where I was a hero, and successful, and loved.

And if I sometimes slipped into Mi-Hee’s world and saw things that weren’t really there, if I sometimes leaned into my fantasies just for the smell of smoke and beach sand, if I found myself draw- ing a special sigil on my apartment doors with my finger to ward off the deaths of my family in strange, gruesome ways—the same way Mi-Hee’s counting warded off evils in the book—well, that was okay, because I had a dream, a story, a new life.

But I was wrong, because the life I live now isn’t new. It’s just a copy of the one I left behind, and I don’t know the way back.

CHAPTER 2

A Box of Secrets

After I hang up on Leoni, after Mi-Hee’s mushroom forest disappears, I take a seat on the plush gray-green couch—Leoni’s couch, because I, of course, didn’t bring any furniture with me when I moved in—and spend an hour trying to turn down the volume on the worries circling my brain, the feeling of unrightness that presses into my skin like insistent fingertips. I need to make sure I’ve got a handle on things, that for at least a little while, I’ll be more firmly in this world than out of it.

There are rituals I can do, ones I started developing long before I’d first read Mi-Hee’s book: counting, reciting, drawing my sigil, moving in symmetrical patterns with the right number of repetitions. Little actions that make me more certain nothing bad will happen, that I won’t lose control of myself—but they’re only partial measures. Not like going out to the Cayatoga Bridge, which tears out my bad feelings at the root.

But I can’t go to the bridge right now. I always go right before midnight, because that’s when I went the first time, when I discovered its power—and I’m terrified if I change any aspect of the ritual, the bridge won’t work for me anymore, and I’ll be stuck here, in this body, forced to trudge through this mess without it.

I decide to do the next best thing—draw my sigil, which is composed of four endekagrams: eleven-pointed, star-shaped forms made by connecting the points of an eleven-sided regular polygon. I draw it on the legs of my jeans, my pointer fingernail tugging gently on the bumps of the fabric. Eleven stacked sigils on one pant leg, eleven on the other, keeping careful count: the more elaborate the shape and the more powerful the number of repetitions, the better it will work, but only if I execute it perfectly, and keep it balanced on each side. Eleven is one of my favorite numbers to use: prime, hard to balance, and uncommon in nature, all of which give it strength—but it’s still small enough and common enough that I feel I can control it.

By the time I’m done, another hour has passed, and I’m almost certain the mushroom forest isn’t coming back. My anger at my roommate, though, is simmering to a boil.

I should be grateful to Leoni, who makes my entire life possible. This apartment may be a disaster—the spots of mold on the popcorn ceiling, the chipped stove with its single working burner, the unpredictable heat that sometimes roasts us in hellfire and sometimes leaves us chilled to the bone—but I also can’t afford it on my own. I’m not even sure how Leoni affords it. I know she likes living in Grand Station for the location and transportation, that between the train, the highways, and the nearby regional airport, it’s easy for her to get to her various travel therapy assignments. The hospital system is also pretty good, which is important—her sister is sick, some disease with a name I can never remember, though I know it’s chronic and makes it hard to breathe, and it means she has to live in a residential care facil- ity with round-the-clock monitoring.

I worry all the time that Leoni will move. If she decides she wants to relocate her main home hub and her sister to somewhere cheaper, I’m not sure what I’ll do. When my temp agency, Spectacular Staffing, called to say they’d found me a placement at a “hospital revenue cycle management” company called Advancex, I’d never heard of it, but they were offering me fifteen dollars an hour. I needed the money, because it was September, and I was sleeping in my car. The days were still warm, but that would change soon. The last remnants of summer in this part of Illinois always break like a wave, less than two weeks before the cold comes on, and the nights were already filling the windshield with frost. There was no way I’d survive dead winter, with its Lake Effect snow.

But I couldn’t work at a place like Advancex without somewhere to stay. I’d just arrived from Pleasance Village and I didn’t know anyone—and I’d been evicted when I failed out of school. Even if I somehow managed to talk a landlord into renting to me, the Advancex building was on Main Street, at the very throbbing heart of Grand Station. No way fifteen dollars an hour would be enough to rent anywhere close to there—and especially not fifteen dollars an hour at a temp job, which didn’t count as real income for any rental agency I called unless I’d been working there full-time for at least a year.

I had no deposit, no acceptable proof of income. I couldn’t get to the job without a nearby (enough) apartment; I couldn’t get the apart- ment without a year at the job. The harder I tried to grab on to the situation, the more it slipped away.

I’ve done a lot of dangerous things in my life, but sometimes I think the worst was posting an ad on craigslist, detailing my situation, begging for help. If someone could take pity on me, if they had a room to rent—I’ll be a model tenant. I have a good job at Advancex and a car. Anywhere within an hour of downtown. Please.

A lot of creeps replied, describing in great detail what they’d do to my hands, my face, my body. But then, like a unicorn parting the glade, Leoni arrived to save me, though I was no deserving virgin as per the medieval stories.

I have a place. It’s not too far from there. You’re . . . not a serial killer, are you?

No, I’d replied, my heart beating as hard as it does when I hike across the bridge. I’m a vegetarian.

So was Hitler.

That was actually a myth created by his propaganda department. As soon as I clicked send, the shock of what I’d done hit me. I’d

corrected this person, the only earnest response to my ad. They were probably never going to reply again—I hoped you’d say that. Do you want to meet up at Bin‐Bash for some coffee and see how we get along?

Thinking now of how I’d held the phone to my chest and cried, my anger cools some—but only a little. The truth is that Leoni doesn’t understand how I feel about Kurt, because she can’t. She doesn’t have a secret like Kurt and I do, access to a world larger than the one she sees.

But when that thought enters my brain, it drags in another—Are you sure? Are you sure?—and suddenly, all the calm I’ve bought myself drawing sigils on my jeans fades away into a sudden itch that can only be scratched by opening the box holding the proof of Kurt’s secret— except that I can’t. It’s not safe time.

Safe time is the short window after I visit the Cayatoga Bridge when I can do things from my list of Nots: all the little indulgences I usually can’t trust myself with, because I don’t know how much is normal, when to stop, or when I’m close to losing control. During safe time, I can drink four iced coffees without feeling like I’m doing something wrong, or watch six hours of Discovery-Bang, a YouTube channel consisting entirely of voiced-over, shaky camera footage as two knuckleheads named Tyler and Josh crawl through Newfound- land forest and abandoned farmhouses to find evidence of fairies and Bigfoot. I can even listen to music, as long as I don’t hum or sing or pay too much attention to it.

In my head, I think of “spending” safe time and “choosing” from the Nots, because safe time is like motivation: it’s in limited supply, and each action brings me closer to the precarious state I spend most days in, when all the Nots start becoming dangerous again. Without the purge of the bridge, any indulgence that feels good—or that lets my guard down—could trap me in a loop, one where pleasure is secondary to stopping bad thoughts and emotions. If I go down that road, it’s hard to come back, like the stomach-sinking feeling of getting home from work and seeing something in your apartment moved. No matter how much you try, you can’t stop checking for more evidence that someone’s tampered with your things.

Safe time is the only time I can look at Kurt’s secret in the box without worrying I might slip into the kitchen-door world so deep that it’s hard to come out—especially lately. But Leoni’s criticism— you don’t even really know this guy—has wormed under my skin like a splinter.

Why can’t she understand that the holes in my knowledge aren’t my fault? The harder I’ve tried to learn about the real man, about his life outside of work, the more elusive he’s proved. But I know about the inside of his mind—that he, like me, contains a hidden depth he never shares. I know what’s really important to him.

Don’t I?

I know the answer, know I know the answer—and still, safe time or not, I get up and walk over to the shelf.

I keep my box with me, always. I even made sure to take it with me when I left the dorms, despite the fact that at the time, any reminder of my parents made me furious and despondent. It’s made of dark brown wood, with turquoise-blue inlay on the lid. The inlay is shiny and ridged, like the rough edges I feel when I run the pad of my forefinger over my bottom teeth. The box has two fake brass hinges that hold the lid to the body, inset deep into rough-carved holes.

My parents got me this box during our only family vacation, when we all piled into the car during one high school summer and drove two days south into Mexico. I still can’t understand why—neither of my parents seemed to like Mexico much, save the beach, and there are plenty of beaches closer to home—but it was the drive down and back that I most cherished: my parents bickering over which music to play, my dad favoring the classical masters, my mom demanding equal time on the tape deck for her favorite teuroteu singers. Each time she won, the car filled with a delicious sadness of floating vibratos and bouncy backbeats, though it was Shim Soo-Bong’s “Geuttae geu saram” that made us all sway together, while Jang Yoon-Jeong’s “Eomeona!” always had us clapping and dancing in our seats. Somewhere in Texas, they even let me play a song from my new teenage obsession, 14 Dogs, though my dad made a face the whole time.

Since then, I’ve kept my secrets in this box. Love notes from boys— and then girls, once I figured out who I really was. Report cards detailing failures in subjects as varied as chemistry, history, biology, and gym. A pornographic picture my once best friend Kim Scott printed from some website we never found again. Kim had run out of red ink, and the naked woman had been an alien blue shade, her body disrupted by static-like streaks.

The box is more dangerous than the other Nots, so I approach it carefully. I pick it up and replace it on the shelf eleven times—eleven is a good number, an endekagram number—and then I take it to Leoni’s bed. Since it’s farthest from the door, it feels like the safest place, the most protected. I can’t risk having some part of the ritual go sour.

In this moment, it strikes me how illogical this is, how disrespectful I’m being of Leoni’s space. I turn toward my bed, but the itching fills me again, and I don’t go any farther. Instead, I push down that kernel of guilt—Leoni’s bed, Leoni’s place, Leoni’s things, oh, but when I moved in here, I’d been so grateful, hadn’t once considered how much harder sharing a bedroom would make everything, hadn’t known about the kitchen-door world, how bad I would get—

There’s a soft rattle emanating from inside the box. I almost drop it, but then I realize it’s because my hands are shaking.

I sink down on her bed, careful, so as not to disturb the fluffy comforter. Bend my knees and drag my legs in close. Her bedding holds the soft scent of her, something clean and vaguely floral, something that makes me realize how stale the rest of this room smells.

I swallow and run my fingers along the box’s edge. Its lid is so tightly fitted there’s a soft grinding as I pull it open, wood against wood, a sound so pleasing my mouth almost waters. And even though I know what it holds, when I see its contents, the random pattern they’ve taken after the box’s many trips onto and off the shelf, I quiver inside with excitement.

Pulling everything out is careful excavation. Somehow, in the shifting, the thing I need has worked its way to the top, the coincidence a proof that feels as strong as any tarot card. It’s a postcard, facedown, just blank lines devoid of addresses, because it was never sent.

It’s Kurt’s.

I don’t remove it. Not yet. Instead, I work my fingers under it, drag out something from beneath—a wooden key chain, the only thing in the box that is mine and mine alone, though I’ve never had it on my keys. The block lettering on the front reads: pleasance twelfth annual band festival, first place.

The white paint is starting to yellow, but its surface is as pristine as the day I was awarded it. I can still remember my father’s face as he handed it over, the soft glow that could only be pride, though now I understand it stemmed from his role as band director, and not as my dad.

My chest throbs. I turn the key chain over and place it south of the box, wiggle my fingers back under the card.

I sneak out two cassette tapes with almost identical labels made of cheap printer paper, cut unevenly enough that they don’t quite fit into their crystalline cases. They’re both from 14 Dogs’s debut album. I even went to a few of their shows, once they’d made it big enough to travel to Grand Station and then Chicago, although “show” is a bit of a grand word for an impromptu gathering of drunk teenagers and college kids in a park.

One of the tapes is mine—an ironic medium, since everybody had long moved past CDs to MP3s by then—but that was the kind of band 14 Dogs was.

The other tape in the box is Kurt’s.

We were riding in the same elevator, and he bent over to tie his shoe, and the tape fell out of his bag and onto the floor. When it became clear he hadn’t noticed, I opened my mouth to say something, but no words came out. I couldn’t even look him in the eye. He got off the elevator, and the tape was still there, so I put it in my bag.

I put the tapes in their places on the bed, one east and one west. Now, the four objects—box, key chain, tapes—form a cross, with a large blank space in the middle. A good shape, a symmetrical shape, though it’s still incomplete.

The last thing in the box is the postcard, which rests not quite flat against the wooden bottom. I pluck it out with both hands and set it in the center spot, still facedown, but I’ve spent so many hours staring at it that I can picture it clearly: a constructed thing, like a child’s art class project. Most of the card’s surface is covered with a roughly cut out swarm of black and white rabbits that I’m sure are from the office printer. There are gaps between the rabbits, though, places where the blue and white streaks of the card’s background extrude out, like when you’re riding in a car past a grove of tight trees and catch strobing flashes of a low-angle sun.

I peeled back one of the rabbits, once. It hurt as much as pulling off a scab, but from the revealed corner, I knew what was on the original postcard—Hokusai’s famous painting, Under the Wave off Kanagawa.

A huge, swirling blue vortex, about to swallow the small mountain in the center.

I lightly drag my finger along the card’s back, under the blank sender address lines. I can almost feel the shape of the letters on the other side. The blocky font looks like it’d feel at place in a seventeenth- century pamphlet were it not for the protective strip of clear packing tape pinning it to the ocean of rabbits:

SOMETIMES, I THINK THERE IS A SECRET WORLD ONLY I CAN SEE, AND ALL THE PEOPLE AROUND ME ARE JUST OBLIVIOUS ACTORS.

Can you understand, now, how it felt to read this? To be standing there in front of Kurt’s open desk drawer, a stolen cassette tape I’d kept hidden for six months clutched in my hand, my heart beating wildly for fear that I’d be caught and have to explain why I’d waited so long to return it? And then to be accosted—no, assaulted—by a confession that mirrors my deepest secret?

Like a brilliant flash of light.

Of course I took it. Of course I’ll never tell. I’d die to know exactly what he meant, how close his fantasy world is to my own—but then I’d have to talk to him. And he might ask for the card back, and I can’t part with it, not yet.

After I first put the postcard in the box, I closed my eyes and tried to find Kurt’s analogue in the kitchen-door world, but when I peered into it, there was nothing there, just a blank space where his kitchen-door form should’ve been. That usually means someone isn’t important to me, but in this case, it confirmed what I’d suspected—that Kurt was a traveler between worlds like me, with no need for an analogue.

Except he’s not like me. He doesn’t have any trouble keeping it together. He’s soaring through the ranks at Advancex, having some- how immediately identified everyone important and how to be their friend.

If I can divine how he does it, maybe I can do it, too.

I grab the corner of the postcard, ready to flip it over, but the urgency, the fire, is gone, replaced by a creeping fear. After all, this isn’t safe time. I haven’t gone to the bridge yet—I’m not supposed to be doing this. If I don’t put this all back now, and shove it out of my mind, I’ll upset the fragile balance I’ve reached with this world and Mi-Hee’s. I could lose what control I have left.

I want to scream with frustration, but I don’t make the rules. After a moment, I stick it all back in the box, get off Leoni’s bed, and put everything back on the shelf.

I told you earlier about my life—the facts of my history, and that they wouldn’t explain why I am the way I am, or how it feels to be the kind of twenty-four-year-old woman who hides stolen things in a box, who’s unsure if a world from a children’s book is real.

Here is a better version.

Let’s say that when you were a child, you read about a girl named Mi-Hee. In your young imagination, she lived in a big, western-style ranch with gardens and a small pool filled with goldfish, because you didn’t yet understand that most Korean houses in the 1960s when the book was first published didn’t look like the homes in your tiny Ameri- can village. They didn’t have separate kitchens and dining rooms, and most of the doors in the house would’ve likely been sliding doors and not ones that swing out. You didn’t know that the book that would come to define you was, in fact, translated, meaning you couldn’t completely trust the accuracy of your mind’s depiction of its contents.

But children are little egoists, and in your imagination, Mi-Hee’s house was like your house. There was a kitchen just like yours, except this one had a skinny door that never opened. The knob didn’t turn, and there was no keyhole or lock. In the book, once Mi-Hee was old enough, this door faded from her mind as if it had never existed— until one night, when she awoke to the smell of smoke. She sprinted out of her bedroom, feet thudding against the floor, only to discover that the entrance to her home was missing, the wall sealed over.

When she turned around, the kitchen door she’d forgotten was there again, only now it was open, and there was daylight spilling through it. On the other side was a white beach full of coconut palms and an ocean whose waves softly lapped at sparkling sand—and because Mi-Hee was young and curious and in danger, she stepped over the threshold.

Let’s say you read this story, and loved it dearly, and then, like Mi-Hee’s kitchen door, it faded from your mind—though not so easily. You were too attached to it, to this girl who was odd like you, who yearned like you, and it was a painful experience to forget it, one full of loss.

Then, one night, you, too, have an emergency. Maybe you are a new college dropout, shivering in the back seat of your parents’ car, realizing that you have no idea what you’re doing, that you’ve got no money and no place to stay. You pass the night in the employee parking lot of a small library, the one you practically lived in as a young child, because it’s the only place that feels safe and quiet and familiar.

Just before dawn, after the stars have faded but before the sky starts to lighten, you think you see something through the glass of the side entrance—a short, bright flash, like the beacon of a lighthouse—and all the hair stands up on the back of your neck.

You crack open the car door and stare at the employee entrance. Something familiar-looking sits on top of the circulation desk, but the glass is translucent with frost, and you’re too far away to be sure, so you creep out of the car, your feet crunching on frozen grass that was asphalt only a second ago. As you approach, the air around you fills with the smell of smoke. You know it’s not real, but you keep moving, pulled forward as if on wires.

It’s not until you’re inches from the glass, until you’ve kicked the rock the staff use to prop open the door and sent it skittering sideways, that you can make out enough to be sure. A book, held up by a small wire frame. The cover faces the employee entrance and not the front door that patrons use, as if it was meant to be seen only by you.

You know this book, because you used to have one just like it. You lost it, somehow, right before you went to college. You tore through your parents’ house on the verge of tears, unsure how you could lose something so important, so needed. Over and over, your mother asked you what you were looking for, but you were too embarrassed to tell her, and by then, she was used to seeing you cry for reasons you couldn’t explain, reasons she would never understand.

But here is your lost book, in the glass. Mi‐Hee and the Mirror‐ Man. You’ve read it so many times you can recite it from memory, trace the arc of the plot like an endekagram, but you’ve always wondered: If eleven-year-old Mi-Hee had known what would happen when she went through the kitchen door, if she’d known about the Wizard and the Mirror-Man and the empty-room ghosts and the unicorns and the Forest That Shimmers as It Sings—would she have still done it? Her house was burning, but there had to be other doors, other windows. The fire crew would have come. If she’d known, would she have stayed instead with her family, her sense of reality, her life? After all, no sane person just jettisons everything they know for a fantasyland.

You’ve read the book a thousand times and never managed to figure it out. But as you stand here, shivering outside the library, the sky just barely starting to pinken, you’re seized with the belief that the answer is in there—in the library, in this book that is almost surely your copy, no doubt delivered to them by your mother as she disdainfully threw away your things. Your ears fill with a familiar piece of music—the one that recently humiliated you—as you grab the door and pull. You’re almost surprised to find it locked.

And suddenly, you see it laid over the library door, as if the two somehow occupy the same space: Mi-Hee’s kitchen door. In that moment, you realize—it doesn’t matter what decision Mi-Hee made. It matters instead what decision you will make—you, who, unlike Mi-Hee, already knows the scope of what is being asked of you, that this decision is permanent—that some doors, once stepped through, seal up behind you, as if they never existed at all.

You, who doesn’t like your life, who doesn’t like your world. You, who’d rather go to never-never land, and never-never wake up.

As you bend down to pick up the rock, your nose fills with the smell of hot sand, and the music crescendos. You throw it, hard, and the door shatters into a crystalline rain, rendered silent by the calls of strings and flutes and horns. You bend down and step through the hole you’ve created, heedless of the jagged rim of glass.

When you straighten enough to get a good look at the circulation desk, the book is gone.

You’re not sure it was ever there in the first place.

A horror overtakes you, but when you shut your eyes, you see around you a tall, enchanted forest, full of pines and spruce, and you realize what you’ve done. You’ve stepped through Mi-Hee’s door, and now, it’s your turn to enter a world full of fantastical, sentient creatures, friend and foe. It’s your turn to go off exploring and have gruel- ing adventures, sure the entire time that these challenges will turn out all right in the end—because, for once, you are the hero of this story, this story whose sole purpose is to mold you into a better version of yourself.

You get back in your car. You push the accelerator down as if the car itself has wings. Only then do you see the cuts on your legs, the red of your blood from the glass, and wonder at your own boldness.

You drive to your new life in Grand Station, because Grand Station is bigger and better, the perfect place to be a bigger, better you.

But shortly after you arrive, you realize how wrong you were. The challenges in Grand Station are no different from the ones you left behind in Pleasance: every problem you come up against here you’ve met before, but at an easier level of difficulty, when all you had to do was be a normal person in a normal place with normal rules.

In Mi‐Hee and the Mirror‐Man, when Mi-Hee breached the Heart of the mountain and uncovered all the mirrors in preparation for the spell that would bring the Mirror-Man into the world, her kitchen door once again appeared behind her—only now, it was painted black.

The sight of it, how closely it resembled something she yearned for, made her feel like she was being torn apart. She wanted so badly to step through it, but the Wizard had warned her in advance that this dark version of her kitchen door was not to be trusted, and so she left it alone.

And you? You leave everything alone, your whole life alone—at least, the best you can. You don’t try too hard. You don’t hope too hard. You tread water and go to work and go home and berate yourself for never being able to put pizza boxes away. Nothing ever changes.

Not until the night you realize that your coworker Kurt Smith is a better version of you, and you suddenly know how Mi-Hee must have felt when the shadow version of her kitchen door materialized behind her in the Heart.

As the teller of this story, I have to wonder: Where do you go from here?

If you were a smarter person, a better person, a more practical person, you wouldn’t have stepped through the kitchen door at all—and even if you had, you would’ve marked where it was, and once you’d done all your growing, you would’ve returned with some new magic that your freshly enlightened self had discovered, and the door would’ve opened. You’d have gone back, back to your life with your many friends and your family that loves you and your good job. It’s possible the door would’ve moved—such is the shifting nature of doors in fantasy worlds—but the point is, you would’ve figured it out. You’d be that main character, dutifully completing your arc of complex growth.

But you are neither smart nor bold. You are a broken person with nothing to go back to, so you decide to just stay in your new life without purpose—only now, you’re damaged in new ways. Everything from your life in Pleasance feels like poison, too dangerous to touch, and over the last three years, in your shitty job, without the support of your family or friends, so many of the habits and behaviors that used to calm you have instead become your master. You’re trapped inside of yourself.

Sometimes, when you sleep, you dream of climbing a mountain, but never reaching the top. In the moments before you awaken, you look down and discover your left ring finger has started to wither away, and you know that this process will slowly spread until it claims the rest of you.

Discover the Book

Katrina Kim may be broke, the black sheep of her family, and slightly unhinged, but she isn’t a stalker. Her obsession with her co-worker, Kurt, is just one of many coping mechanisms—like her constant shape and number rituals, or the way scenes from her favorite children’s book bleed into her vision whenever she feels anxious or stressed.

But when Katrina finds a cryptic message from Kurt that implies he’s aware of her surveillance, her tenuous hold on a normal life crumbles. Driven by compulsion, she enacts the most powerful ritual she has to reclaim control—a midnight visit to the Cayatoga Bridge—and arrives just in time to witness Kurt’s suicide. Before he jumps, he slams her with a devastating accusation: his death is all her fault.

Horrified, Katrina combs through the clues she’s collected about Kurt over the last three years, but each revelation uncovers a menacing truth: for every moment she was watching him, he was watching her. And the past she thought she’d left behind? It’s been following her more closely than she ever could have imagined.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next