Dark City: The Mistress of Suspense

When Alfred Hitchcock arrived in Hollywood in 1939, he had an ace up his sleeve, a female protégé who would become a crucial figure in noir—Joan Harrison. She made waves as one of only three female producers in a male-dominated business (Virginia Van Upp and Harriet Parsons were the others), and industry scribes worked themselves into a lather describing how this “feminine fireball” challenged the status quo while “wearing an evening gown with the same eye-filling éclat as Lana Turner.” Harrison’s rise was related as a fairy tale in which a British lass went from shopgirl to secretary to screenwriter to shot-caller (“. . . but for a trick of fate, she might today be one of millions tending babies in English cottages,” claimed one hack). But the bottom line is that Joan Harrison was essential to development of the film noir movement. Her sensibility was attuned to psychological thrillers and she crafted them with a keen story sense and a strong guiding hand, every bit the equal of her counterparts Mark Hellinger, Hal Wallis, and Jerry Wald. Over the entirety of her professional life, Harrison rarely strayed from the shadows—her career arc tracing, precisely, the trajectory of noir in the culture’s bloodstream.

In 1933 Harrison had answered an ad Hitchcock had placed, looking for an assistant. The director, working at Gaumont British studios, was won over by her intellect, charm, and taste for the macabre. Her fascination with crime was fostered by her uncle, Harold Harrison, a “keeper” of the Old Bailey, in charge of scheduling cases in London’s criminal court: “He was one of those uncles young girls adore,” Harrison said. “He not only took you to lunch, he knew the grisly details of all the most shocking crimes.”

Joan Harrison became Hitchcock’s “reader,” and soon collaborated in meetings, not merely taking notes but offering suggestions. The female lead in The Lady Vanishes (Paramount, 1938), played by Margaret Lockwood, bears a significant resemblance to Harrison. If Hitchcock’s wife, Alma Reville, was threatened by her husband mentoring this young woman (Harrison was twelve years younger than the Hitchcocks), she betrayed no jealousy—even when Harrison got a cowriting credit (with Sidney Gilliat) for 1939’s Jamaica Inn (Paramount). Despite collaborating on every facet of her husband’s films, Alma never earned a credit more significant than “Continuity.”

When the Hitchcocks sailed to America to discuss adapting Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca for producer David O. Selznick, Harrison traveled with them as family. The registry listed her as “Joan Hitchcock.” Friends and associates called them the “Three Hitchcocks.”

On Rebecca (UA, 1940), Harrison received coscreenwriting credit (with Robert Sherwood)—and an Oscar nomination. She was now integral to the development, scripting, and preproduction of Hitchcock’s films: earning cowriter credit on Foreign Correspondent (UA, 1940), Suspicion (RKO, 1941), and Saboteur (Universal, 1942). Rumors arose: Harrison was the real talent behind Hitchcock, or an especially “personal” assistant. The “Three Hitchcocks” ignored the gossip, but before Saboteur was in the can, Harrison opted to forge out on her own.

Her search for an appropriate project led to a novel by Cornell Woolrich—the type of story she’d previously have taken to her mentor. Her first-draft adaptation convinced Universal to let her build it as a feature. Being a woman, she was granted only “associate” producer status—even though there were no other producers.

Lunching at a bistro favored by European émigrés, Harrison encountered a director who shared her interest in crime stories. Despite an accomplished career in Germany, Robert Siodmak’s Hollywood years had been spent freelancing on B movies. It was his 1942 Fly-by-Night, made for Paramount’s B unit, in which Harrison recognized a variation on Hitchcock’s approach—the elegant commingling of shadowy mystery, whipcrack pace, and sly sexuality,as well as a flair for dynamic set pieces. She signed Siodmak up as director of her breakout project, Phantom Lady.

With this 1944 release, Harrison not only helped foster the film noir movement, she set the course of Siodmak’s career. Some critics, such as The Nation’s James Agee, intrigued by the possible emergence of a female Hitchcock, considered Phantom Lady entirely Harrison’s handiwork. His review discussed “Harrison’s use” of light and sound—never mentioning the actual director.

Harrison and Siodmak reunited for a film version of Thomas Job’s daring 1942 Broadway hit Uncle Harry. The heavy hints of perversion in its three-way romantic triangle appealed to them both. They also reunited with actress Ella Raines, who’d starred as “Kansas” in Phantom Lady. Uncle Harry was Raines’s third film with Siodmak in less than two years. In each she played a self-sufficient and bracingly modern young woman. Raines noted in interviews that she gleaned the persona from her producer, Joan Harrison.

Production of Uncle Harry was a blissful affair—but things soured when Universal altered its ending. When it was announced that (retitled) The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry would be test-screened, Harrison sniffed defeat. The test audience of “bobby-soxers” led to Universal creating five endings—none good. Harrison walked off the lot, burning a major bridge behind her. “If my standards as a producer and writer were to be subject to the whims of the front office,” she declared, “then the only thing for me to do was leave.”

Dore Schary, RKO’s chief of production, welcomed Harrison to his studio. They shared a desire to make edgy, tightly scripted thrillers on modest budgets. Her first RKO effort, 1946’s Nocturne, saddled her with an incompatible leading man—George Raft—and his “personal” director, the prodigiously untalented Edwin L. Marin. Harrison still crafted a nifty noir, buoyed by a clever Jonathan Latimer script, a colorful supporting cast, and the evocative cinematography of Harry Wild.

They Won’t Believe Me (1947) was a more serious affair. Developed by Harrison and Latimer from a story by Gordon McDonnell, it’s the producer’s finest film. For this Cain-style saga, she deep-sixed genre conventions. Instead, she crafted a story about an homme fatal (Robert Young) whose behavior ruins three women. As played by Rita Johnson, Jane Greer, and Susan Hayward, these are the most authentic jilted wife and “other women” in noir—no femmes fatales or Pollyannas here. Real people die, not plot devices—a rarity for the genre.

Harrison’s new studio-home was ransacked in late ’47 when it was purchased by Howard Hughes; following Schary’s lead, Harrison bolted for less volatile environs. Ironically, she landed back at Universal—where Robert Montgomery (another pal from the Hitchcock days) asked her to produce his follow-up to The Lady in the Lake. Harrison strode straight into hard-boiled terrain—adapting a novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, self-admitted devotee of Hammett and Chandler.

Ride the Pink Horse is a picaresque revenge thriller as well as a despairing take on the sprawl of American corruption. For the screen version—drafted by always reliable Ben Hecht—Harrison again ran up against the intractable adolescence of the Production Code. Its mandated changes (such as transforming the villain from a homicidal senator into a garden-variety gangster) diluted the book’s profound bitterness into petulant sourness. The novel’s vicious antihero, known only as “Sailor,” emerges on-screen as truculent “Lucky” Gagin (Montgomery). The movie has an off-kilter energy and enough trapdoors and funhouse mirrors to make it unique. Although he’d have been wise to cast someone with more gravitas as Gagin, Ride the Pink Horse is unquestionably Montgomery’s finest work as a director.

While Harrison’s collaboration with him was fortuitous, the allegiance she showed Montgomery—one of her most admirable traits—was ill-advised. Two more films with him (Once More, My Darling [Universal, 1949], an unfunny comedy, and Eye Witness [Eagle-Lion, 1950], an intriguing but listless courtroom drama) squandered Harrison’s talent at the height of the noir era. Circle of Danger (RKO, 1951) followed, a whodunit with a few Hitchcockian moments. It’s no lost classic, but it let Harrison cap her movie career with something worthier than those Montgomery misfires.

Joan Harrison’s career, however, was far from over. If anything, she was about to have a renaissance. By the early ’50s, her mentor was the most recognized movie director in the world, and his agent, Lew Wasserman, suggested Hitchcock double-down on his popularity by conquering TV as well. Hitchcock was wary, afraid of stretching himself too thin. Wasserman suggested he bring Joan Harrison back into the fold.

Their reunion resulted in one of the greatest television shows of all time. Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the thirty-minute anthology series, ran for seven years before morphing into The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in its final seasons, 1962–1965. Harrison produced 266 installments of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, hiring veteran directors (John Brahm, Robert Stevenson, Paul Henreid, Robert Florey) as well as newcomers (Arthur Hiller, Stuart Rosenberg, Boris Sagal, Robert Altman). Ida Lupino directed two episodes, even though Harrison once said, facetiously, that women don’t make good directors: “To be a director you sometimes have to be an S.O.B. It is much harder for a woman to be this.” In interviews, Harrison deployed dry British wit, giving expected answers a droll twist.

In a 1957 interview, realizing she’d forever be linked with Hitchcock, Harrison expounded upon her own approach to suspense, dropping all ladylike pretense: “Let ’em suffer,” she said, referring to the viewers. “Let ’em become participants in the show and twist and turn with every twisting and turning. That’s why I’d rather make shows with ordinary persons for characters—secretaries, housewives, a man in an ordinary job. Not the so-called upper classes. They lead a particular kind of life. Hitch is a member of the great middle class and he knows these people. When he thinks about stories of the ordinary person, he’s absolutely wonderful. . . . The most interesting murderers are the most mild-seeming men. Inside, the most extraordinary things are happening to them.”

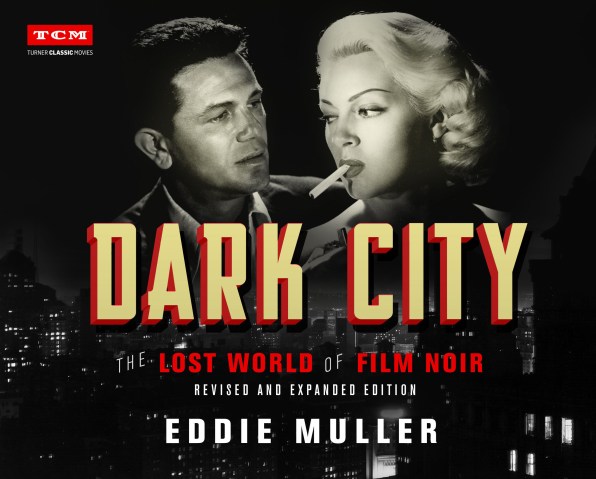

Excerpted from DARK CITY: The Lost World of Film Noir (Revised and Expanded Edition) by Eddie Muller. Copyright © 2021. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

About the Author

Eddie Muller, aka the “Czar of Noir,” is the host of TCM’s Noir Alley franchise, and the prolific author of novels, biographies, movie histories, plays, and films. He also programs and hosts the “Noir City” film festival series, curates museums, and provides commentary for television, radio, and DVDs. As founder of the Film Noir Foundation, Muller has been instrumental in restoring and preserving more than thirty lost noir classics. He resides in Alameda, CA.

Dark City expands with new chapters and a fresh collection of restored photos that illustrate the mythic landscape of the imagination. It’s a place where the men and women who created film noir often find themselves dangling from the same sinister heights as the silver-screen avatars to whom they gave life. Eddie Muller, host of Turner Classic Movies’ Noir Alley, takes readers on a spellbinding trip through treacherous terrain: Hollywood in the post-World War II years, where art, politics, scandal, style—and brilliant craftsmanship—produced a new approach to moviemaking, and a new type of cultural mythology.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use