The Unreliable Narrator

In any story, the narrator is our guide, shaping the way we see settings, characters, and events. No matter who the narrator is—first, second, or third person—we as readers are affected by the way the story is told to us through the narrator. Everything we learn and everything we know is seen through this filter. So what happens when we as readers can’t fully trust what a narrator is telling us? That’s when you have an unreliable narrator.

In any story, the narrator is our guide, shaping the way we see settings, characters, and events. No matter who the narrator is—first, second, or third person—we as readers are affected by the way the story is told to us through the narrator. Everything we learn and everything we know is seen through this filter. So what happens when we as readers can’t fully trust what a narrator is telling us? That’s when you have an unreliable narrator.

An unreliable narrator is a narrator whose credibility has been compromised in some way. And while the unreliable narrator trope has become extremely popular in the mystery, suspense, and thriller genres, you can find unreliable narrators in all sorts of stories. Unreliable narrators are featured in all kinds of film and literature, from thrillers and suspense to fantasy and sci-fi to children’s stories.

The term “unreliable narrator” was coined by American literary critic Wayne C. Booth in 1961. In The Rhetoric of Fiction, Booth wrote that a narrator is “reliable when he speaks for or acts in accordance with the norms of the work (which is to say the implied author’s norms), unreliable when he does not.” This definition suggests that an unreliable narrator occurs when the reader and the author share a version of reality to which the narrator does not conform.

But let’s break that down a little bit more and look at some examples.

Here’s the deal. There is more than one way a person’s narration can be unreliable. In Living to Tell About It, literary critic James Phelan expanded on the duties of the narrator and the ways narrators can be unreliable. According to Phelan, it is the job of the narrator to “perform three main roles—reporting, interpreting, and evaluating; sometimes they perform the roles simultaneously and sometimes sequentially.” So based on these roles, there are a few different ways narrators can be unreliable.

First of all, an unreliable narrator might misreport, misinterpret, or misevaluate what they are narrating. Sometimes this is intentional, sometimes it’s by mistake. There’s also unreliability through the act of leaving out important details. In other words, narrators might also underreport, under-interpret (or underread), or under-evaluate (or under regard). So, basically, is a narrator telling the story incorrectly? Or are they not telling the whole story? Either way, their story becomes unreliable.

While this all may sound good in theory, how does it work in actual fiction?

Here are some examples (warning: some details here may be considered spoilers):

On a warm summer morning in North Carthage, Missouri, it is Nick and Amy Dunne’s fifth wedding anniversary. Presents are being wrapped and reservations are being made when Nick’s clever and beautiful wife disappears. Husband-of-the-Year Nick isn’t doing himself any favors with cringe-worthy daydreams about the slope and shape of his wife’s head, but passages from Amy's diary reveal the alpha-girl perfectionist could have put anyone dangerously on edge. Under mounting pressure from the police and the media—as well as Amy’s fiercely doting parents—the town golden boy parades an endless series of lies, deceit, and inappropriate behavior. Nick is oddly evasive, and he’s definitely bitter—but is he really a killer?

A murder in a small English village leads Hercule Poirot into a strange mystery involving a determined, curious spinster, the local doctor, and a wide range of suspects with possible motives and mysterious relationships. Poirot retires to a village near the home of a friend, Roger Ackroyd, to pursue a project to perfect vegetable marrows. Soon after, Ackroyd is murdered, and Poirot must come out of retirement to solve the case.

The novel was well-received from its first publication in 1926. In 2013, the British Crime Writers' Association voted it the best crime novel ever. It is one of Christie's best-known book, its innovative ending having a significant impact on the genre. Howard Haycraft included it in his list of the most influential crime novels ever written.

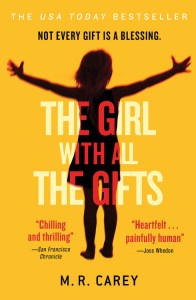

The Girl with All the Gifts by M.R. Carey is an excellent example of a narrator underreporting because of a lack of knowledge about the world around her. This book is narrated by Melanie, a young girl who knows that she is special, but no one will tell her exactly why. She lives her life in a cell, and every morning, someone come to bring her to class at gun point. She thinks it’s because no one likes her, but as readers follow her narration, they will begin to understand the world Melanie lives in and why she’s so special, even when Melanie herself might not be so sure.

Christopher John Francis Boone knows all the countries of the world and their capitals and every prime number up to 7,057. He relates well to animals but has no understanding of human emotions. He cannot stand to be touched. And he detests the color yellow.

This improbable story of Christopher's quest to investigate the suspicious death of a neighborhood dog makes for one of the most captivating, unusual, and widely heralded novels in recent years.

Now that we’ve looked at some of examples of unreliable narrators and what unreliable narrators do, the question remains: why? Why feature an unreliable narrator in your story? Why are unreliable narrators so popular, especially in crime fiction?

For those of us who love mysteries, thrillers, and suspense stories, we love to feel like we’re a part of the action. An unreliable narrator requires the reader to be an active participant in the story. We can’t just sit back and accept the reality presented to us because we know the narrator might not be telling the whole truth, for a wide range of reasons. Beyond the story, this makes the narration itself into a puzzle. What can we trust? What blanks are being left open, and what information can we fill out just by paying close attention to what the narrator doesn’t tell us? Or doesn’t want us to know? Asking these questions and search for answers is endlessly fascinating. And so fun. This is why the unreliable narrator will always be a mainstay in the world of fiction.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next

Emily Martin has a PhD in English from the University of Southern Mississippi. She’s a contributing editor at Book Riot and blogs/podcasts at Book Squad Goals.