Who Tells It In The Whodunit: The Role of The First-Person Narrator

Imagine that you are reading a mystery novel. The detective and their assistant have just discovered the body, and all the clues and evidence are piling up.

However, through whose eyes are you seeing the action?

Is it from the point of view of the detective or the sidekick? Or an innocent (so they say) bystander? Or from a detached third-person narrator?

The role of the narrator plays a pretty big part in how you read a mystery novel. If you’re reading a book told in the first-person, that can affect what the reader sees, and how they see it.

Sherlock Holmes has Dr. John Watson, of course, and Nero Wolfe has Archie Goodwin. Hercule Poirot has a number of people, from frequent sidekick Captain Arthur Hastings to bystanders like hospital nurse Amy Leatheran.

It is safe to say that most people reading this essay have never been actively involved in a murder investigation: as a witness, a suspect, or as the investigator. Therefore, when we read about murder cases, it is from the standpoint of the average person on the outside; indeed, the reader is another bystander looking on from outside the yellow crime scene tape.

We usually learn about the case after the fact. None of us have actually looked at the evidence with our own eyes. Similarly, the first-person narrator, unless they are the detective, may not be privy to all of the facts of the case, or even any of the facts. (Granted, not even the lead investigator may be privy to any or all of the facts.)

All of us have our own opinion about who the killer is and how the murder was done. This opinion is formed on what information we have seen, and also, to be perfectly frank, our own personal biases. “Oh, he did it, definitely. It’s always the husband.” “Oh, there’s no way she could have done it! Such a nice, pleasant person.” So may it be with a first-person narrator. They may be a little too quick to eliminate certain suspects, or to concentrate on someone who turns out to be innocent.

The first-person narrator is a link between the reader and the events of the book. They may be asking the questions that the reader wants answered. The narrator may also represent a more “normal” person, or at least, someone who is slightly more normal than the often eccentric detectives they work alongside.

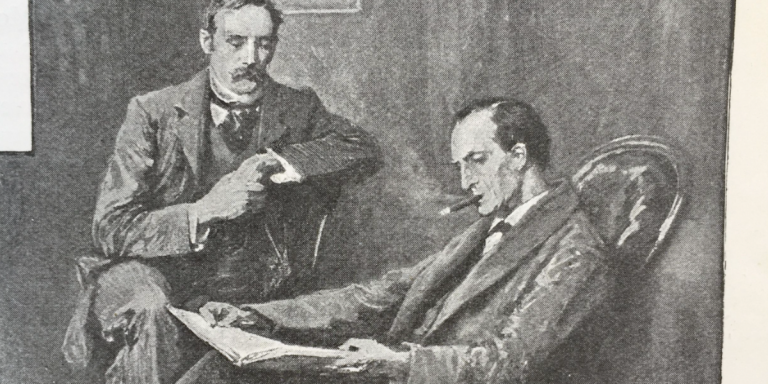

HOLMES AND WATSON

The great detective and his faithful scribe make their acquaintance in A Study in Scarlet. Watson, an army doctor, has just returned to England from extended military duty in Afghanistan and is looking for someone to rent lodgings with.

As Watson is the narrator for all of the Holmes novels and stories, our perception of Holmes is entirely through his eyes. We find ourselves wondering, as Watson does, who this strange man is, with his bizarre personal habits and obsessive knowledge about crime and criminals. Watson’s own life is somewhat more conventional compared to Holmes’s; he acquires a wife in “The Sign of Four” and settles down to life as a London doctor and family man. In this way he is somewhat of a foil to Holmes and his assorted quirks.

At other points in the story, Watson may be off on his own business around London, only to return to Baker Street and find that Holmes has been busy unearthing all manner of clues, and consuming copious quantities of tobacco and coffee in the process.

Watson’s role is largely that of narrator, mirror, and sounding board. Every now and then, some hints about Watson’s personal life will enter the narration, usually in response to one of Holmes’s questions, but aside from that, we don’t see very many hints about Watson’s home life or personal feelings.

Holmes is largely absent from The Hound of the Baskervilles. He is—so Watson believes—back in London carrying out his own investigation. So it comes as a surprise to Watson, and the reader, when Holmes appears on the moor. The reader, like Watson, is probably feeling surprised and frustrated that Holmes has finally shown himself after so long an absence. But then, all is revealed. In true deus ex machina fashion, Holmes reveals some major bombshells about the Stapletons: information that has largely been kept from the reader.

WOLFE AND ARCHIE

Fifty years or so later and on the other side of the Atlantic from Holmes and Watson, Rex Stout introduced readers to Nero Wolfe and his narrator-sidekick Archie Goodwin. Wolfe makes his home in an elegant New York brownstone, tending to his rare orchid plants in between solving baffling cases, while Archie works the front desk, does a lot of “shoe leather” work for his boss, and enjoys the life of a man about town.

Archie, at the outset, could be seen as the Watson to Wolfe’s Holmes. But Archie is a wisecracker and a smart-aleck: a snappy foil to the more aristocratic and sedentary Wolfe. It’s a bit of the reversal of the formula of “eccentric detective, more normal sidekick” trope, in that both the detective and the sidekick are fairly outrageous characters in their own way. Archie gets into his own fair share of ludicrous scrapes over the course of the average investigation, including

It is anyone’s guess how many of Archie’s biographical details are true, given that the name of whichever Ohio town he was born in seems to change from book to book. If that is the case, the more cynical reader can guess that Archie may be taking poetic license with some of the details of whatever case he and Wolfe are working on.

From time to time, Watson or Hastings will snap at Holmes or Poirot with an impatient clap back such as “Go to the devil!” But Archie seems to be a lot more generous with his clap backs at Wolfe.

Archie and Wolfe’s relationship definitely seems to be more employer-employee than with Holmes and Watson or Poirot and Hastings, whose relationships are more of two longtime friends or colleagues.

POIROT AND ASSOCIATES

Unlike Holmes and Wolfe, Hercule Poirot does not have one person who serves as his sidekick-scribe for all of his adventures. Instead, the role has been shared by a number of Poirot’s friends and acquaintances.

Probably the most notable of these is Captain Arthur Hastings, who serves as narrator for 26 short stories and eight novels. (In the long-running television series starring David Suchet as Poirot, Hastings—portrayed by Hugh Fraser—takes on an even more prominent role; the scriptwriters added him to several stories in which he was not originally present.)

Similar to Holmes and Watson’s first encounter, Poirot and Hastings first make each other’s acquaintance in The Mysterious Affair at Styles; Hastings is an army officer recovering from war injuries, and Poirot is a refugee from war-torn Belgium.

In this early book, Hastings considers himself to be a pretty good detective; he claims to have learned a few tricks from Poirot, and to have even surpassed Poirot in some ways. But the truth is, Poirot’s “little grey cells” outstrip those of Hastings by a long way. On more than one occasion in other stories, Poirot will calmly, coolly reveal a piece of evidence that goes completely against Hastings’s own theories, much to the latter’s chagrin.

Hastings is a “typical” upper or upper-middle-class English gent. He has a strong sense of honor, he is a firm believer in fair play (some of Poirot’s detection methods shock him a bit), and he is unfailingly polite to beautiful women: something that periodically trips him up, to Poirot’s amusement.

Some of the other Poirot narrators include Nurse Amy Leatheran in Murder in Mesopotamia, Colin Lamb in The Clocks, and Dr. James Sheppard in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Their own roles vary; Nurse Leatheran had been attending to Louise Leidner, the victim, before her death. Lamb gets drawn into a murder investigation purely by chance and asks Poirot for his advice. And Sheppard, one of Poirot’s new neighbors in the detective’s (short-lived) retirement, works alongside Poirot to help gather evidence.

For several Poirot novels, Christie switched to a semi-omniscient third-person point of view, including for Murder of the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, and The Mystery of the Blue Train. Of these, Murder on the Orient Express follows Poirot constantly, while the other books begin with chapters following the soon-to-be victims and suspects; Poirot himself does not appear until several chapters in.

The ABC Murders takes a somewhat different approach. The book is largely narrated by Hastings, but includes a number of chapters told in the third person, labeled “Not from Captain Hastings’s personal narrative.” In the prologue, this is explained by having Hastings write the scene based on information given to him by Poirot. There is a touch of poetic license, but Hastings tells the reader that Poirot had vetted all of those chapters.

The Narrator Did It!

There are at least two Christie novels in which the narrator turns out to be the murderer, and in some cases, the killer had been working directly alongside the detectives on the investigation.

Perhaps we may see this as a subtle trick to put the reader on the wrong path. After all, how many of us would believe that the narrator or the detective’s assistant could very well be a suspect? Would this person’s status as narrator somehow put them above reproof in the reader’s mind?

On subsequent readings, the reader may notice some subtle hints in the narrator’s voice that suggest they are hiding something: a certain bitterness about certain characters, or perhaps some hedging on rather uncomfortable questions.

The fact that the murderer is telling the story is a pretty good example of an unreliable narrator: they are leaving certain facts and contexts out of the story. “I trekked through the snow to the old man’s house and found his corpse,” they might say, without mentioning that they had caused the old man to become a corpse earlier in the evening.

Christie wasn’t the first author to write a crime story narrated by a killer, of course. A frequently cited example is Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

Poe is often credited as having “invented” the detective story with The Murders in the Rue Morgue. But Poe’s goal is to unsettle and frighten the reader with tales of the uncanny, the macabre, and the downright scary. Thus it is with “The Tell-Tale Heart.” It is clear from the outset that the narrator is planning to kill the old man with whom they live. Instead, the story’s emphasis is on drawing the reader into the narrator’s more and more unbalanced mental state, and inducing growing feelings of terror, uncertainty, and paranoia. The description becomes so vivid, so overpowering, that the reader can easily imagine that they are the ones trying to conceal both a dead body and a guilty conscience.

Is the narrator telling the truth about being fond of the old man, of having no ill will toward the man or a greedy desire for his money? Or that they are quite sane about what it is they are doing? The astute reader has good reason to question this as the story unfolds.

In a mystery novel, the person who is doing the storytelling is just as important as the crime, the evidence, and the outcome. The narrator is a link between the reader and the action, a means for the reader to ask questions, occasionally a source of comic relief, and in a lot of cases, a person who will keep the reader guessing and occasionally lead them down the wrong path. And that can heighten the stakes in a well-written mystery novel and keep the reader coming back for more.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next

Erin Roll is a freelance writer, editor, and proofreader. Her favorite genres to read are mystery, science fiction, and fantasy, and her TBR pile is likely to be visible on Google Maps. Before becoming an editor, Erin worked as a journalist and photographer, and she has won far too many awards from the New Jersey Press Association. Erin lives at the top floor of a haunted house in Montclair, NJ. She enjoys reading (of course), writing, hiking, kayaking, music, and video games.