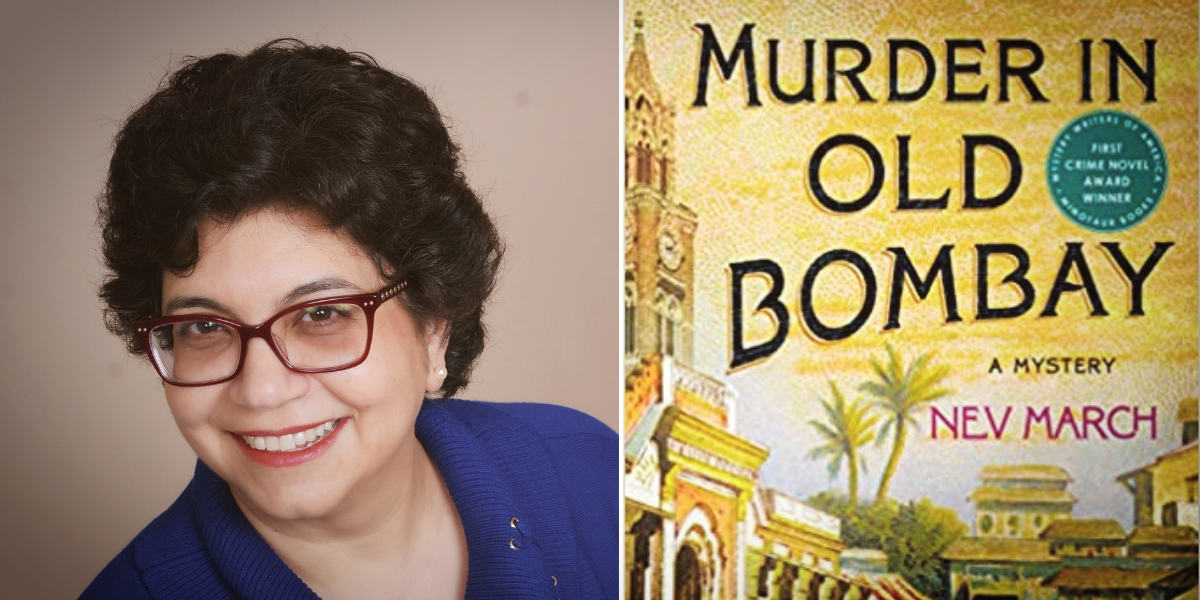

Keeping It Fresh With Mystery Suspense Author Nev March

What makes a piece of writing something you want to keep reading? What makes it intriguing and puzzling and yes, welcoming? Why do we slip into some stories and keep going through without fatigue? Clear, easy writing has that effect, but I think there’s something more–it’s fresh.

What makes a piece of writing something you want to keep reading? What makes it intriguing and puzzling and yes, welcoming? Why do we slip into some stories and keep going through without fatigue? Clear, easy writing has that effect, but I think there’s something more–it’s fresh.

“Fresh” is not easy to define. It’s easier to explain its absence—when an article goes too long, no matter whether it’s in the New York Times, a novel or Yahoo News, I find myself skipping ahead. Not a good sign. It usually means that unless my eye hooks onto something interesting soon, and I mean SOON, I will X out (if on the screen), scroll away (on my phone) or close the book. The piece had my attention, and alas, lost it.

Fresh writing keeps me interested. It STAYS fresh. While teaching myself to write fiction I pored through craft books, working diligently through a dozen or more, doing EVERY exercise, working my way carefully through them, digesting the examples, even reading the books the examples came from.

When I began to write novels my reading changed. If I found a book that had me grinning with satisfaction when I set it down, I said a mental note, “How does she DO that? I’ve got to look at it again.” Sometimes, on the second go around the effect was difficult to see. The element of surprise was lost, the flow, the rhythm was already known. But I’d try. How did Dashiell Hammett manage such a compact plot in ‘The Maltese Falcon’? To study this, I examined the plot by creating an outline

utline for his book. First, I summarized each chapter in a sentence or two. Then I put it all together and examined how it links and holds and echoes, and warns, and surprises and explains. That’s brilliant plot, brilliant writing. It’s fresh and it stays fresh.

Reading hundreds of novels, and dissecting some, gives us an appreciation of that special ether, that ‘freshness’ that Ken Follet calls “the turn”. He points out in his brief Masterclass: The plot must turn every four pages, to move the action ever forward. The story delivers meaning, emotional impact.

Reading his novel Pillars of the Earth and its sequel World Without End I found myself utterly engrossed—multiple protagonists each with a set of problems and multiple antagonists! How does he do that?

“How good does a work of art have to be, to be good?” famed science fiction writer L Ron Hubbard asks, in his essay “Art, More About.” The answer surprised me: It takes “Technical expertise adequate to produce an emotional impact.”

Huh? Adequate technical expertise? I feel as though Beethoven just waved me off with, “Practice, my dear!”

Yes, Hubbard claims, before the audience sees the message, they notice the expertise of the artist. That in itself, draws a

positive reaction. The artist “knows what he is doing. And how to do it. And then to this he adds his message.”

Wait—that’s it! The message! But no, a message without the technical expertise to carry it, is boring, preachy even. Hubbard points out artists need the expertise “to produce an emotional impact.”

But how? How does one craft words into garlands of sentences that do this? It has to do with feeling the emotion as one writes, I think, remembering, imagining, and then burning that thought into the page with words. Feeling empathy for the character is not enough. A writer must be deeply engaged, to

figure out why and how the character experiences that emotion, and how they react. And yes, she must write it all down in compact language. That’s the technique Hubbard is talking about, the skill to paint word-picture that move and live like movies, only better, because the reader is inside the character’s head.

Hubbard says, “A lot of artists are overstraining to obtain a quality far above that necessary to produce an emotional impact. And many more are trying to machine-gun messages at the world without any expertise at all to form the vital carrier wave.” He’s saying the very mastery

of technique forms a “carrier wave” that reaches a reader—the closest thing to telepathy, perhaps, a carrier wave of language and emotion.

So how do we keep generating fresh ideas? Reading books in different genres helps. Reading poetry also fuels the engine. And I find that mysteries come in many different styles. When I read Sue Cox’s The Man on the Washing Machine I had an immediate sense of place—the tiny San Fransisco suburb, almost a village in the middle of San Fran’s hilly st

reets and corner cafes. And there was more: how can a murder mystery where the body count keeps rising be terrifying and thrilling and even contain moments of side-splitting humor? Somehow Sue Cox manages to achieve this intoxicating cocktail.

Joanna Schaffhausen’s All the Best Lies, is book three of her Ellery Hathaway series. “Ellery, however, stalked death like it owed her something. Like they had unfinished business. Maybe that’s why the bullets came flying every time Reed got near her—he was always in the way.” I felt a frisson of alarm run over my skin as the pair search for his Reed’s mother’s killer, on a trail that becomes deadlier by the page-turn. Now that’s suspense, that’s emotion.

When I wrote and rewrote chapters of Murder in Old Bombay, I reviewed alternatives the way an actor says his lines a hundred times, trying out different tones. My early readers, bless them, helped me see which version had an emotional impact. Writing is something we learn to do around the age of five. But writing well? Writing fresh? Ah, now that’s a skill. And writing with sufficient expertise that our message delivers an emotional impact? Now that’s the goal of a professional author.

In 1892, Bombay is the center of British India. Nearby, Captain Jim Agnihotri lies in Poona military hospital recovering from a skirmish on the wild northern frontier, with little to do but re-read the tales of his idol, Sherlock Holmes, and browse the daily papers. The case that catches Captain Jim's attention is being called the crime of the century: Two women fell from the busy university’s clock tower in broad daylight. Moved by Adi, the widower of one of the victims—his certainty that his wife and sister did not commit suicide—Captain Jim approaches the Parsee family and is hired to investigate what happened that terrible afternoon.

But in a land of divided loyalties, asking questions is dangerous. Captain Jim's investigation disturbs the shadows that seem to follow the Framji family and triggers an ominous chain of events. And when lively Lady Diana Framji joins the hunt for her sisters’ attackers, Captain Jim’s heart isn’t safe, either.

Q: Thanks so much for speaking with us, Nev. We’re excited to learn more about MURDER IN OLD BOMBAY. First and foremost, you started out as a business analysis and now you write mysteries. Have you always had a passion for writing? What drew you to mysteries? Did your previous work influence how you approached plotting a novel?

A: I’ve always loved reading, and by extension, writing fiction, starting with short stories and poems when I was eleven. Mysteries interest me because of the hidden aspect—why isn’t the answer or solution apparent? What emotion caused that crisis? My career in analysis was a high-pressure one with multiple projects and deliverables. It taught me to organize my time and materials—my files, research sources, and promotional assets. My training helps me plan a lot, to create a well-researched, detailed outline. I use market research to find information and solicit input from critique partners. Using Excel, I work out cause and effect, where to plant clues, what information is missing, what surprises are in store for the detective, (and reader) and the emotional journey across chapters. Writing a mystery has both emotional and analytical aspects, which makes it complex to write.

Q: MURDER IN OLD BOMBAY is based off a true story. What about this story caught your eye and made you want to discover more?

A: As a child I’d heard of ‘the Rajabai Tower Mystery’—the tale of two Parsi girls who fell from Bombay University clock tower in broad daylight. Though these were officially ruled suicides, my family remembered this as a cautionary tale to warn girls of danger in a big city.

When I read how they died, some things stood out as odd. First, that they didn’t die at the same time. I had a feeling that if this was suicide, they would have held hands for courage, and jumped together. Second, three things were missing from their bodies! Bacha’s head scarf, her sacred thread (Parsees tie it around their waists with 2 sets of reef-knots) and Bacha’s spectacles. That set me off, scouring every account of the case I could find.

Turns out that the husband of one of the victims was Ardeshir Godrej, who went on to become a famous entrepreneur and inventor. At the time of his wife and sister’s deaths, he was a 22-year-old law student. He never remarried, so I thought he must have been deeply in love with his young bride. How does a young man recover from such a blow? From his remarkable achievements in later life, I wondered whether he’d hired a detective! He would not want more publicity… that was the start of my plot. What sort of man would he hire as private detective? At the time, British army officers often retired to take up private employment. So, I invented a lonely young soldier, recovering from injuries and wanting a family of his own.

Q: Your novel takes place in 1892 British India, a time as vibrant as it was contentious. I imagine there are many things you had to be mindful of while staying historically accurate. What type of research did you have to do in order to capture the essence of India in the late 1800s. What challenges did you have to navigate? And what are some interesting facts you may have learned?

A: Writing about a different time in a different place poses significant challenges: Some words weren’t in use in the 1890s—I had to checked the origin many words, often finding that they came into our vocabularies after the world wars. While I knew Indian history well, since I grew up there, and was avidly interested in history, yet I learned some horrific details about it. An ancestor of mine wrote an eyewitness account of the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, a book that was a family secret until India’s independence in 1947. I had it translated, and used elements in my novel. I read accounts written during the times, by British administrators, newspapers and Cornelia Sorabji’s adventures as Indian’s first female lawyer working for the “Court of Wards” that administered hundreds of estates and Princely States.

I’d been to and lived in many locations mentioned in my book. With special permission, since it’s closed to the public, I even climbed Rajabai Tower where the two women’s deaths occurred. By poring through portraits and records of Victoria Cross, and Medal of Honor recipients I studied the battles and skirmishes of the time.

One significant challenge was to write about positive and negative aspects of both colonizers and colonized. As an Indian immigrant I represent the colonized perspective. However my community the Parsees were very Anglicized, many were loyalists, lawyers and reformers. So that gave me a unique perspective to show both sides.

I learned a great deal about the history of Princely states; many Raja and Nizams were benevolent and progressive. But I uncovered cruelty and tragedies—some are preserved in folklore, because these crimes were hushed up by powerful rulers. I learned that 40% of Guyana’s present population is descended from indentured workers and slaves of Indian origin who were either kidnapped or tricked onto ships and could never return to India. Many went aboard ship during the Bengal famines. However, this trade escalated after slaves could no longer be procured after the American Civil war, because the demand for labor in the islands continued. That surprised me, because I’d not heard of this trade in trafficked individuals while living in India.

The official version of Indian history tends to paint British rule as harmful and Indian Rajas as heroes. I realized the truth is far more complex and unpleasant—in many ways Indian society itself was misogynistic and cruel in the 1800s, perpetrating caste-based crimes with impunity—some that continue until today! Google ‘Hathras rape of Dalit Woman’ to read about a vicious crime committed only months ago! It should motivate people of all castes to demand action and not protect perpetrators.

Q: You also teach fiction writing. Do you have any advice for budding authors who want to delve into the mystery suspense genre?

A: Writing mysteries is difficult, yet enormously rewarding on a personal level. To start with I wrote Historical fiction and historical romance—haven’t published these yet. They were great practice in building the narrative, learning to build interesting characters, state an intriguing problem, to balance emotion and action, dialog and narration, and propel the story forward.

With a mystery a writer has additional tasks: To set up a believable solution to the crime and the progress toward it, as well as to surprise the reader. That’s a delicate balance! The end must be both inevitable AND surprising. It must satisfy, both intellectually and emotionally. This requires a great deal of introspection, digging deep within ourselves, into our most painful memories, regrets, fears and doubts. It means dredging up truths, and empathizing deeply with your characters.

Yet, when done right, the effect is marvelous. I have wept, while writing certain chapters. I’ve found myself jumping up off my chair, after reading a powerful chapter from my favorite author. Writing is more absorbing than anything else I have done. A book is a powerful medium to transport us and bring insight! Do the work, train yourself, and engage. Have fun diving into it.

A: You have talked about writing a sequel to this book, can you give us any hints about this new book or any projects you may currently be working on?

Yes! I’m working on a sequel set in 1893 Chicago, where twenty-seven million Americans will visit the Columbian Exposition that summer. Captain Jim sets off to investigate a murder at the World’s Fair. When he doesn’t return, Diana travels into unknown terrain in search of him.

Chicago hosts the first Parliament of World Religions that summer, while at the same time, the World Convention of Anarchists has assembled. What could possibly go wrong? When this pair of young immigrants discovers a possible plot to blow up the World’s Fair, the stakes rise—everything they care about is at risk, even each other.

Order Now

“Murder in Old Bombay delivers a gripping look at India’s history, resplendent with meticulous research and depicting its social structure enhanced with realistic characters who put the past in context with modern times.” — South Florida Sun Sentinel

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next