J.A. Jance On Writing For Everyday People

J.A. Jance On Writing For Everyday People

J.A. Jance On Writing For Everyday People

When it’s time to write a book, I fly without a net. I start at the beginning and write to the end, some 100,000 words later. There are writers who swear by writing in longhand. Not me. I bought my first computer, a dual floppy Eagle with 128 K of memory, in 1983 and have been working on keyboards ever since. There are writers, J.K. Rowling among them, who don’t put words to paper without knowing exactly where they’re going. Rumor has it that J.K. didn’t begin the first Harry Potter book until she had outlined the entire series. That’s not me. I met outlining in Mrs. Watkins’s sixth grade geography class. I hated outlining then, and nothing that has happened to me in the intervening decades has changed my mind. What I do is start at the beginning and write to the end.

Since I write murder mysteries, I usually start with someone dead or dying and then spend the rest of the book trying to figure out who did it and how come. If I knew the answers to those questions at the beginning of the book, there would be no motivation to write it. I write for the same reason readers read—to find out what happens. Through the years I’ve learned that the first 20% of any given book is the hardest part to write. Because I write books in series, the beginning of each book must introduce both new characters as well as continuing ones. It’s a tightrope act, because I have to bring in the ongoing characters in a manner that gives new readers enough information to feel at home in the book without boring my longtime readers to tears.

I count the words every day. (My computer does.) My goal at the start is 95,000 words. Why is that? A standard shipping box contains 40 hardback books—as long as they’re approximately 100,000 words long. Am I offended that the length of my books is dictated by the size of the cartons? No. Was Michelangelo miffed that the size of his painting was limited by the walls of the Sistine Chapel? I aim for 95,000 words to tell the story. If I’m a thousand or two below or above that when I finish the rough draft, I have a 5000-word margin to use for tying up loose ends if, during the editing process I discover I’ve dropped a stitch or two.

As I said, the first 20 % of any given book is the most difficult. The middle 60% is, in many ways, a lot like slogging through mud. The finally 20% is easy. I call that the banana peel of the book. It’s the point in the story when, for both writer and reader, you don’t want to stop until you get to the end. By the 80% mark I usually (not always) know who the killer is, and it’s only a matter of getting all the necessary characters to turn up at the same place in time for the crashing climax.

When I first started writing dialogue, I used to read it aloud to make sure that my characters sounded like people talking rather than people making speeches. I no longer have to do that because I’ve taught myself how to hear the words in my head as I write them.

I write for ordinary people. I avoid using words that would send readers in search of their dictionaries. And I try my best to avoid, what my high school journalism teacher referred to as “gray space.” If there are only two or three paragraphs covering a page, there’s not enough happening in the story. Readers tend to skip over the “boring” parts, so I leave those long, wordy passages on the cutting room floor.

Years ago, I was told by the director of a university-level Creative Writing program, “We don’t do anything with genre fiction here. We only do literary fiction.” That’s a direct quote by the way. Well, I’m proud to be a writer of “genre fiction.” As Tony Hillerman once told me, “Literary fiction is where not much happens to people you don’t like very much.” And the truth is, I like my characters. J.P. Beaumont and I have been author and character for almost forty years now. When it’s time to write about him, it’s only a matter of pages before I’m back in his mindset and his world. The same holds true for my other characters as well. I like them. Starting a new book about one of them is like getting a holiday letter from someone you seldom see but you still want to be in touch with them and theirs and know what they’ve been up to.

The ancient sacred charge of the storyteller is to beguile the time. And that’s what my books are supposed to do, all of them constructed the hard way—one word at a time.

Order Now

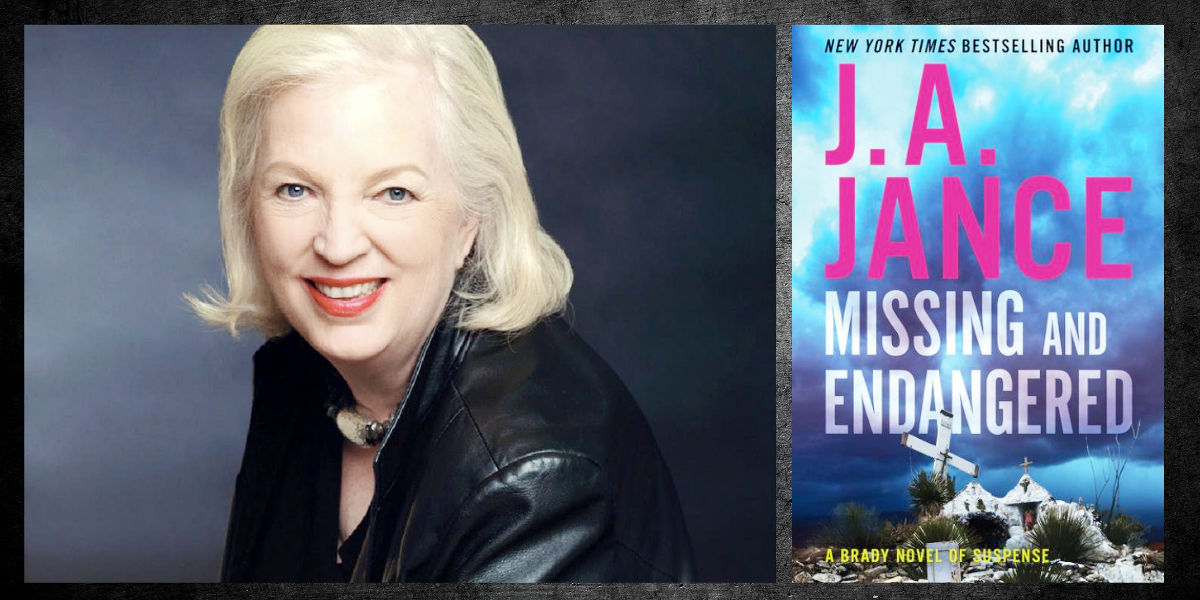

Cochise County Sheriff Joanna Brady’s professional and personal lives collide when her college-age daughter is involved in a missing persons case in this evocative and atmospheric mystery in J. A. Jance’s New York Times bestselling suspense series, set in the beautiful desert country of the American Southwest.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next