How Heather Chavez Comes Up With Characters

Before I was a writer, I was a voracious reader. In elementary school, I consumed books the way other kids might consume candy: quickly, grabbing any I could find. My dad’s old paperback copy of James Michener’s Hawaii. My aunt’s stash of Harlequin romances. My own gifted copies of Nancy Drew mysteries. And, of course, the book that changed everything for me—Dean Koontz’s Whispers.

As an adult, I wrote a very bad first novel. And another. And another. (I’m nothing if not tenacious.) As I began drafting my fourth book, I couldn’t figure out why it, too, wasn’t working. (Now it’s pretty obvious I was trying to be another Koontz instead of finding my own voice, but back then I was flummoxed.)

But then I had “The Idea” that became my first published novel. If reading Whispers was my first career-defining moment, this was my second. I was suddenly sure I wanted to write stories where ordinary people were tested under extreme circumstances. Thrillers allow us to work through trauma or fears in a safe space, but they’re also escapist, and intimate, probing the darker side of humanity—the secrets and thoughts our family, friends, and neighbors keep hidden.

Most importantly, for the first time, the voice I heard in my head was my own.

Having figured that out, I now just had to take The Idea and make it a 90,000-word book in my voice, as well as create the distinct voice of my point-of-view characters. Easy, right? (In case the sarcasm doesn’t translate: No. Not even a little bit.)

That first novel, No Bad Deed, started out as a third-person, three POV story. In my second draft, I ended up scraping two of the POVs to concentrate on the voice I heard loudest, and that I considered most important: Cassie, a mom and veterinarian searching for her missing husband.

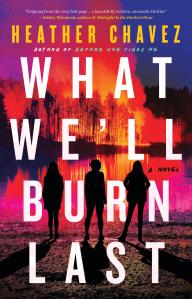

In my last book, Before She Finds Me, two characters demanded their place on the page: single mom and botanist Julia and pregnant assassin Ren, connected by a tragedy and their love of plants. And What We’ll Burn Last tells the story of the complicated women—Leyna, her estranged mother Meredith, and neighbor Olivia.

Through countless hours of reading and drafting, I’ve learned many crucial lessons: the importance of pacing and a good edit, for example, and how to create a process that works for me. But, mostly, I’ve learned to listen to the voice in my head, and to create characters I’m compelled to spend time with through the long months of drafting and editing—and beyond, because the characters you’re most passionate about tend to stick with you.

Part of my drive to create complex female characters with agency comes from my real-life role as mom to a fierce, complicated young woman. I want to do right by her, and by readers. Because while readers are often drawn to a book for its premise, they stay for the characters.

I sometimes describe my characters as strong, but what that means is distinct for each of them—as it is for each of us. For instance, I’m pretty good in a crisis, as long as that crisis doesn’t require that I run, lift anything heavy, or reliably know my north from my south.

Exploring the layers of my characters—and finding the “strengths” and flaws that make them unique—is one of my favorite parts of the process. I’ve even started completing Enneagram quizzes for my characters. (What We’ll Burn Last’s Leyna is a Type Five/The Investigator, in case you’re wondering.)

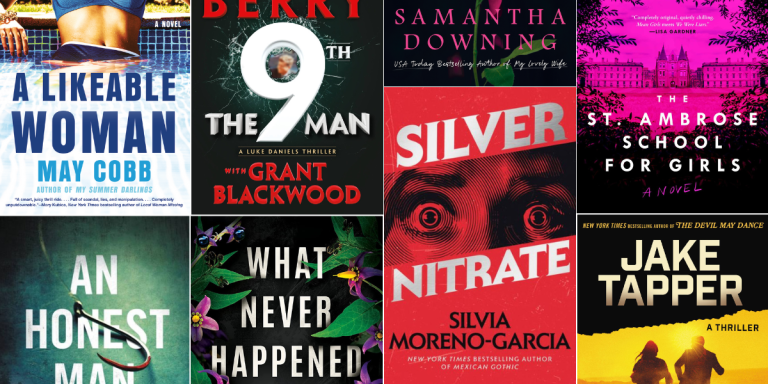

Some female characters I find especially compelling:

Camille in Sharp Objects by Gillian Flynn is an addict and self-harms, but even as she struggles with these demons, she has agency. She isn’t waiting for answers—she’s actively pursuing them.

Vera in The Soviet Sisters by Anika Scott is highly intelligent, patient, strategic, and ruthless. And yet she is working for a higher purpose. Vera is compelling because she exists in an authoritarian system, and she’s able to twist it for herself and her family.

Marie in American Spy is resourceful and resilient as she deals with issues of race, gender, and family as a federal agent during the Cold War. The Last Thing He Told Me’s Hannah must protect her teen stepdaughter, Bailey, after her husband/Bailey’s dad disappears suddenly. (A fantastic example of how nurturing can be a formidable strength.)

Karin Slaughter’s books are a masterclass in how to write complex women, and complex female relationships. The opening chapter of The Good Daughter features a portrayal of motherhood that is fierce and fresh. The same goes for the relationships between the sisters in False Witness and Pretty Girls.

So what defines a strong and complex female lead? In my opinion, she’s someone who makes clear choices, even if her choices end up being wrong, and attacks problems in a way unique to her. She’s flawed, because it is often how we grapple with our flaws that make us most interesting. She possesses clear wants, needs, and morals—she’s not bad or good. She just is.

Discover the Book

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use