Crime Fiction and the American Great Depression

The attitudes of the 1920s and the 1930s diametrically opposed. I’m sure you remember the bootlegging demi-criminal of the Roaring Twenties, the man who “saw an opportunity, I suppose,” as Gatsby says of Lansky, and got his foot in the door of a booming business that happened to be illegal. Let me rephrase: when alcohol was illegal, nearly everyone was a criminal…except the criminals.

The attitudes of the 1920s and the 1930s diametrically opposed. I’m sure you remember the bootlegging demi-criminal of the Roaring Twenties, the man who “saw an opportunity, I suppose,” as Gatsby says of Lansky, and got his foot in the door of a booming business that happened to be illegal. Let me rephrase: when alcohol was illegal, nearly everyone was a criminal…except the criminals.

By that, I mean, if they didn’t want to criminals didn’t have to get too dirty. Really, by making a whole segment of the economy illegal, many regular businesspeople became criminals, and the real criminals, the ones who worked in gambling and sex work and violence, well, they already had the network. Why get your hands dirty when you can just get them a little soiled?

In the 1920s, fresh off the Allied Victory, things were looking up. Americans and English were optimistic, and the publishing world entered its “Golden Age” of detective fiction. Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers ruled the shelves, their whodunnit novels marked by cozy setting, a layperson detective, a complete defiance of Occam’s Razor and a total escapism for your pleasure.

As a result of the stock market crash in 1929, banks went under. People who had worked and saved their whole lives lost everything, and vast companies that provided work for hundreds all folded. Opportunities dried up, and that changed the vibe.

As far as actual crime, bank robberies were happening country-wide, some of the robbers becoming Robin Hood-like folk heroes, like Bonnie and Clyde, or Pretty Boy Floyd. They were a sort of hope to the working folks who had been turned out on their ass. Many of them became criminals out of necessity, even if just vagrancy or theft to survive.

When Prohibition was federally repealed in 1933, everything went back to being regulated, including the formerly illegal business of running booze.

That meant that the criminals of the 20s went back to being real criminals: rather than just smuggle booze, they fell back on the old trusty “loan-sharking, labor racketeering, and drug trafficking.”

Working men everywhere—including Veterans from the Great War—got laid off as a result of the economic decline. Like President Franklin D. Roosevelt said after repealing Prohibition, “What America needs now is a drink.”

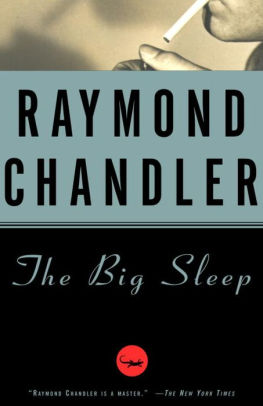

What most of them needed was a job. One such unemployed man was the famous crime fiction author Raymond Carver, who turned his bad luck into fortune by selling his first story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” and then his more famous novels like The Big Sleep.

What most of them needed was a job. One such unemployed man was the famous crime fiction author Raymond Carver, who turned his bad luck into fortune by selling his first story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” and then his more famous novels like The Big Sleep.

Rather than the beach-read escapism that was so widely enjoyed in the 1920s’ Europe, America went hard-boiled.

As a result of the change in American attitude, the mood of crime fiction totally changed, too. Readers went from solving murders based on children’s nursery rhymes in the 20s to following the loner tough guy P.I. down the mean streets of (insert big city here… but usually L.A.). You know the type: he fuels his insubordination on black coffee and cigarettes and he drinks heavily. The cases were just as complicated, but now we have a professional on the scent.

Why the change? It’s not hard to hypothesize. Americans were disillusioned of the meritocracy on which the country was allegedly founded. They were suddenly unemployed or married to unemployed drunks that couldn’t provide. Or they were widowed in the Great War and forgotten by the government. Even onscreen, the government was supposed to be the hero there for a while. Instead of the folk hero criminals being reflected on the silver screen, Hollywood went another way. Instead, G-men (or Government Men), agents of the FBI as run amok by J. Edgar Hoover, became the films’ heroes, whereas hard-up criminals like James Cagney’s Tom Powers (of Public Enemy) were the antagonists.

It doesn’t seem like the film industry could really read the room as well as noir writers like Dashiell Hammett, Jonathan Latimer, or Mickey Spillane. That is, until they got Bogey to star in the books’ adaptations.

If you ask me, which you didn’t, readers lost their appetites for mysteries that fell into place in 1929. It was a nice fantasy, that everything could be tied up with a bow, but once the country incurred these very real hardships, they preferred being represented as an anti-establishment private investigator, an entrepreneur who kicks ass, even if he can’t make rent.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next

Mary Kay McBrayer is the author of America’s First Female Serial Killer: Jane Toppan and the Making of a Monster. You can find her short works at Oxford American, Narratively, Mental Floss, and FANGORIA, among other publications. She co-hosts Everything Trying to Kill You, the comedy podcast that analyzes your favorite horror movies from the perspectives of women of color. Follow Mary Kay McBrayer on Instagram and Twitter, or check out her author site here.